“Andy Goldsworthy: Fifty Years”, Edinburgh Art Festival review

Mark Brown in Edinburgh

9 August 2025

Andy Goldsworthy – the English artist whose unique work is made, for the most part, in and from the natural world – has been engaged in his internationally acclaimed practice for half a century. To celebrate that milestone the National Galleries of Scotland is presenting a major retrospective exhibition at the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) gallery in central Edinburgh.

Andy Goldsworthy, “Fence”, 2025.

Courtesy of the artist.

Although Goldsworthy is celebrated primarily as a visual artist, his work has always been cross-disciplinary. In particular, it has, since the outset of his career, involved a performative dimension in which the artist places his own action at the heart of the work.

This aspect of his output stands in a rich tradition that includes ancient pagan rituals, Dadaist performances, live art “happenings” and the public art-making of Jackson Pollock. The Canadian theatre critic – and early practitioner of happenings – Gary Botting wrote that: “Happenings abandoned the matrix of story and plot for the equally complex matrix of incident and event.” As numerous films and photographs in the Edinburgh show attest, Goldsworthy’s work has often been characterized by the staging of his artistic creation as an “incident” or “event”.

More than that, the experience of the viewer in relation to Goldsworthy’s works is often distinctly performative. For example, one of numerous large-scale pieces in the RSA exhibition is Oak Passage (2025), a work that was first constructed in a farmer’s shed in Dumfriesshire.

Built of large branches from a dead oak tree (Goldsworthy’s practice famously does no harm to the natural environments in which he works), the piece creates a pathway with banks of branches on either side. The branches are arranged in such a way as to have perfectly straight edges. Inevitably, the work invites, almost demands, the viewer to walk along the path the artist has created. The combination of the natural quality of the branches (which evoke a forest) and the straightness of the pathway (which speaks to the history of human construction) makes one’s perambulation (or, indeed, perambulations) through Oak Passage a genuinely singular experience.

Andy Goldsworthy, “Elm leaves held with water to fractured bough of fallen elm”.

Dumfriesshire, Scotland. 29 October 2010.

Courtesy of the artist.

This sense of participation – which adds to the complex experience of “seeing” explained by John Berger – recurs throughout this wonderfully diverse show. Red Wall (2025) – a work of cracked red earth from Dumfriesshire – may be new, but it is emblematic of Goldsworthy’s body of work.

There are remarkable photographs, including shots of Fallen Elm (2009, ongoing), a piece in which the artist uses elm leaves in warm colours on the fissures that opened up in a tree that died of Dutch elm disease. The visual effect is extraordinary, creating the illusion of fire burning around the edges of a dark chasm in the tree. The implication of the violence of the disease on the once living body of the tree is powerful indeed.

Filmed works in the exhibition are often reminiscent of the output of the late, great American video artist Bill Viola. For instance, Tapping water, New Hampshire, 20 May 2023 shows the visually dramatic impact – in terms of the creation of a constant ripple effect – of simply putting one’s index finger into a stream.

Goldsworthy’s work often has subtle political implications embedded within it. This is certainly true of Red Flags (2020), a series of 50 flags that the artist dyed with earth from each of the states of the US.

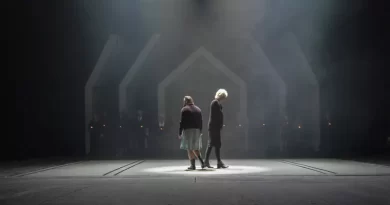

Perhaps most powerful, however, is Fence (2025), a large-scale work constructed of recovered barbed wire tied between two grand pillars in the RSA. One encounters the piece as one climbs to the top of the stairs to enter the exhibition.

The art work connects, no doubt, to Goldsworthy’s historical interest in questions of land ownership, and the barriers and restrictions that come with it (he has, at various points of his career, been forced to leave areas in which he was working by unsympathetic landowners). However, in these days of genocide in Gaza and burgeoning authoritarianism in much of what has, in the post-Second World War era, been considered the “democratic world”, one experiences Fence as an altogether more universal and sinister work.

Of course, the pieces referenced above represent only a small proportion of the extensive and impressive array on display in this beautifully curated exhibition. At the RSA until 2 November, this show is a fascinating and absorbing delight, both for Goldsworthy aficionados and art lovers who want to know more about one of the UK’s finest living artists.