“Am Ziel”, Burgtheater, Vienna

Axel Hörhager in Austria

18 March 2023

Only Thomas Bernhard, with his acerbic and typically Austrian wit, could have commented on his own success with the bemused detachment found in Am Ziel. His creations both eulogize and downplay the playwright’s efforts; hinting at Pirandello, the characters even complain that he, the Author on stage, is simply using them and their utterances to gratuitously advance his personal belief that the world is going down the drain.

Dörte Lyssewski and Maresi Riegner.

Photo credit: Susanne Hassler Smith.

A Mother (Dörte Lyssewski) and a Daughter (Maresi Riegner) – neither are ever named – do indeed talk plenty (especially the Mother) during their two-and-a-quarter-hour tour de force on stage with the Author (Rainer Galke). Am Ziel (loosely translatable as “On Target” in the sense of attaining a final destination) premièred in 1981 at the Salzburger Festspiele. The play was revived for the Burgtheater under director Matthias Rippert in October 2022 and is now in repertory.

The play sees the Mother telling of the highs and lows of her life-journey in the form of monologues ostensibly addressed to her grown-up though still young daughter. The Daughter utters few words and plays along with her mother who has engulfed her since childhood and shows no signs of letting up. Is this mother-child dynamic surprizing in the home country and town of Sigmund Freud who claims a child’s love for the mother is the model for all subsequent love relationships?

In act one, the unequal pair interacts in a stage space dominated by two black rows of numbered theatre seats (designer Fabian Liszt) where they sit. Once the mother’s tales of woe relating to her unhappy family life are temporarily exhausted, the new theme is their recent encounter with a successful playwright (the Author) after an acclaimed performance. The Mother spontaneously invited the playwright to join them in their annual trip to the seaside.

The mother is fed up with the way her life has turned out. She admits that she never really loved her husband – the owner of a foundry who owns the house by the seaside. Under the influence of the cognac that she drinks in ever-increasing quantities, she tells her daughter, in an obviously well-rehearsed litany, of how she married on the advice of a female friend who was attracted by what her husband-to-be represented rather than what he was. And sure enough, their first-born, a son, was an unloved, ugly creature she wished had never been born and who obligingly passed away while still an infant. The daughter we now see beside her came along later and clearly meets the expectations of any family. Her mother feels that the only successful thing to come out of her marriage is her daughter. And now, seeing that her daughter is potentially marriageable, the mother spontaneously invited the author but is clearly not willing to let go.

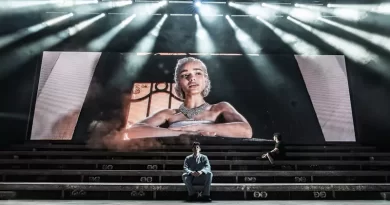

Rainer Galke, Maresi Riegner and Dörte Lyssewski.

Photo credit: Susanne Hassler Smith.

Despite the Mother’s claim that the Daughter is free to engage with any young man she takes a fancy to, it is clear who is running the show. Not only does the Mother take spiritual possession of their new Author friend and travel companion, but she also uses the occasion to fire salvo after salvo at the superficiality, ridiculousness and indeed perversion of the Author who is in her eyes undeservedly fêted by the public. Her own low moral standards, her materialistic view of everything, and most of all her self-pity leave us amazed at the fact that eventually in Act Two the three are together at the seaside, sitting on a bench to view the seashore.

The Mother tells the Author some more home truths that (not mistakenly) she assumes will eventually end up in his plays. This Mother is an egotist through and through, from emptying the cognac, to grabbing the only warm coat leaving the Author shivering in his light clothing, to never asking herself why she should spoil even the few moments of momentary lightness of being and happiness that sometimes break out of the Daughter, allowing her to survive. An off-putting climax is reached when under the influence of too much drink, the Mother (who is not actually portrayed as an alcoholic) throws up on the author’s shirt, and he is left to deal with the consequences. More upsetting, though, is how the Daughter is not allowed any autonomy. The two are a well-oiled team with rituals that the mother will never allow to be disrupted, and the daughter is too weak to seriously envisage a separation.

What do deeper philosophical or other insights matter if acquired on the back of depraved inter-personal relationships, Bernhard asks. The Author is a powerless observer who thinks he can “change the world” but comes to the realization that the world doesn’t want to be changed – and that it doesn’t matter anyway. So, we are left with the gratuitous affirmations that come out of the mother’s mouth for want of anything better.

A riveting performance that catapults us from Beckettian monologues through Pirandellian introspection to a Shakespearian sense of the tragic but always in the cynical sour-tempered perspective of Thomas Bernhard. Incidentally, the Author’s acclaimed play is quoted as Rette sich wer kann, which the French expression sauve qui peut or the English Every man for himself aptly encapsulate. At the end of the day, 42 years later, Thomas Bernhard is still fully on target.