Actress Caroline Peters interviewed by Dana Rufolo in Vienna

September 2024

German actress Caroline Peters is not new to Plays International & Europe. I interviewed her in 2016 for this magazine when it was still published in a paper format in an article entitled Caroline Peters and Sylvie Rohrer: European Actresses in Love with Language.

Since then, Peters has seen her career soar. She has worked with important European directors like Thomas Ostermeier, Milo Rau and Simon Stone (for whom she played the lead in his German version of Yerma). She had the female lead of the mother – renamed Christina in this Maja Zade version – in Ödipus (Oedipus) directed by Thomas Ostermeier. I reviewed the play when it toured from Berlin to the Almada Festiva in 2022.

Peters is a member of the Vienna Burgtheater’s actor ensemble, and has twice won the Nestor Prize and Actress of the Year Prize from Theater heute. Her novel Ein anderes Leben (A Different Life) is scheduled for release on 30 October 2024 by Rowohlt Publishing Company, Berlin.

After an engagement at the Schaubühne in Berlin, she has recently returned to Vienna and is presently engaged to act in Milo Rau’s Resistance Now! dramatic and political Austrian project.

Caroline Peters is a deep-voiced actress with an expressive mobile face. Her characterizations are well thought-through; she is especially appreciated for her use of understatement and controlled, even suppressed, emotion. Known for energetic changes of mood on stage, the energy is nonetheless contained by the character and never appears to engulf or threaten the characters around her. Often, critics give Peters the credit for keeping alive a play or production that is otherwise hackneyed or flawed.

The focus of this interview is Peters’ engagement in the Resistance Now! dramatic and political Austrian project of Milo Rau which is raising consciousness about the danger of electing a right-wing government in Austria, (thereby voting to suppress freedom of expression in the arts) in the 29 September 2024 elections. Peters is part of a group of theatre personalities leading the movement that include Mavie Hörbiger, Elfriede Jelinek, Birgit Minichmayr and Claus Philipp.

In agreeing to be a leader activist, Peters is tacitly agreeing to a Europe-wide call to action. Rau has spoken of the Resistance Now! project as a larger European project on September 19. He read his proclamation “How to Resist”, at the International Conference of the International Theatre Institute (ITI)’s meeting entitled Embrace and Connect in Antwerp. Additionally, on November 4, the European Theatre Convention (ETC) embraces Rau’s approach of active and targeted resistance under the title “Free Culture: Resisting Political Interference” at its European Theatre Talks meeting in Liège, Belgium.

[The interview was conducted in English and took place in Vienna on 6 September 2024. ]

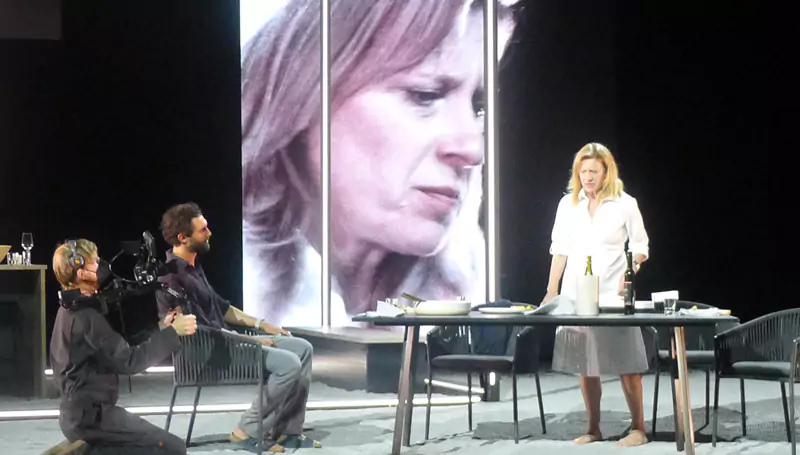

Caroline Peters in The Machine Stops by E.M. Forster.

Photo credit: Frank Dehner.

DR: You have been a professional actress for over 30 years now. Could you briefly bring us up to date on the trajectory of your career?

CP: At the beginning of my professional career, I worked a lot with René Pollesch who later became the director of the Berliner Volksbühne. Pollesch was a writer and a director at the same time, and I think that was an important part of my training. I was not only in classical plays but also new plays and was thinking about the time we are living in and why we are doing this kind of theatre [“discourse theatre”]. And then I was lucky enough to work with Luc Bondy; I learned a lot about character in classical plays. Then I was very happy when I met Simon Stone who was not only directing but also writing, and we did five or six plays together over the past years and that was actually the most important part of my work.

DR: Bringing us up to the recent present, how did you handle the Covid period, when theatres went dark?

CP: I think during the pandemic in the German-speaking world of theatre everything changed even more than in the English-speaking world, because Germany has state-funded theatre and the companies were still paid and we could still live off our jobs, but we were working into the void. We were all rehearsing and not showing anything. It was a very strange situation for everybody and it made the whole process a little bit absurd and weird.

Also, a whole generation went into retirement during that time, and there was a generational shift during a period when no shows were being presented. Topics like performance as opposed to the classical play – with the performance idea gaining strength – and gender or the woke movement were all in the middle of the theatre discourse all of a sudden, and they weren’t there before the pandemic. And now, nobody really knows what’s important any more.

I have the feeling that during the pandemic everybody radicalized themselves in a certain way. Every person, privately, on their own. And now something is coming out, represented best by Milo Rau at the moment, which is trying to make art a force of political meaning or political consequences. Really doing something instead of just putting on a play that is nice to watch. I’m personally not sure what to think about this, but I’m very interested in being close to what is new in theatre. I think that is totally new: to say art is a form of political resistance and it is much more than art, and theatre doesn’t stop at the end of the stage, it goes on into the public space in general. That is what Milo is doing.

For me, for the upcoming season, I’m doing both things that I feel exist in parallel at the moment. First, I’m in a normal play – just a real play with fictional characters; people can watch it and see themselves in it and be represented by us actors on stage. That will be in the Akademietheater (a Viennese theatre owned by the Burgtheater). It’s the play Egal (Whatever) by Marius von Mayenburg with Thomas Jonigk doing the staging and the directing; that’s going to open on 15 February, 2025.

The other is a show with Milo Rau which is more about political interaction with people outside the theatre community. We don’t exactly know yet when this will go on. We will do the original play Burgtheater by Elfriede Jelinek at the Burgtheater, and that’s a big thing because it was once forbidden and Jelinek didn’t give the rights after that, so it is an event to do it there at the Burgtheater where it once had been forbidden.

DR: It is a Viennese tradition to refer to the Burgtheater in Austrian plays. Bernhard’s “Heldenplatz” (“Heroes’ Square”) for example. Or his “Claus Peymann kauft sich eine Hose und geht mit mir essen” (“Claus Peymann Buys a Pair of Trousers and Goes out to Dinner with Me”).

CP: Yes, but it is not just the play. We will also do a lot of political interaction and … fighting in the streets? I really have no idea what it’s going to be!

DR: Fighting like, “Here’s my rubber club; it has ‘human rights’ written on it!” Perhaps?

CP: That’s right. Basic human rights. That’s what we all have to fight for all of a sudden. We haven’t been there yet. My parents were there when they were kids. And now, it’s back.

DR: So you will act in “Burgtheater” at the Burgtheater but also you are part of Rau’s Resistance Now! You will be expected to participate in street demonstrations?

CP: I have no idea! I’m totally looking forward to it, and I think we are expected to participate in the whole thing. We already published a proclamation in the newspaper and on social media and everywhere – to stand together against the FPÖ [Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs – the right-wing Freedom Party of Austria] and we say to read their programme carefully and to really understand that if you give your vote to that party, you are going to change democracy permanently. Because that’s what they want to do. As soon as they can make the laws, they will change them in an unfavourable way for people who like to be free. And we try to point that out. Also, the FPÖ wants to stop funding events like the Wiener Festwochen (Vienna Festival Weeks), of which Milo Rau is now the director. They say, we will never fund this kind of art. State money is put into theatre so there can be different ways of looking at things, and people are free to have different opinions, but the FPÖ intends to dictate to the theatres, stating we’ll give money to the theatres as long as they say what we want them to say.

DR: Of course there is the transcendent funding system, which is the EU’s Creative Europe programme. That would allow an escape from the prison of the Viennese perspective. But I take it that the Wiener Festwochen is dependent on Austrian grant-funding, and that is a restriction.

CP: That’s a danger all of a sudden, and it never has been, because a big part of Austrian economic life is art. Tourists come in to the country because of art. And it’s very important to the people of Vienna as well. They all go. This suddenly stopped during the pandemic, and it started very slowly after that.

It’s totally the opposite here in Vienna from Berlin, where there hadn’t been a good relationship between the theatre and the audience. Since the pandemic ended, all the Berlin theatres are crowded. Only now are theatres getting audiences again in Vienna, but it took a long time to get there. It started with Milo Rau’s Wiener Festwochen 2024; it made a big splash in the whole city. And then the new start in the Burgtheater; everybody is very happy about the new director.

DR: You’ve won a lot of prizes recently. What’s your interaction with the public like these days?

CP: I do so many different things, and they each have a different kind of pubic and audience. For the German public, I am known for a TV series I did 15 years ago, and people still talk to me about it on the street. It’s on reruns and Netflix.

Then, theatre has its own very special crowd. I’ve been working at the Schaubühne in Berlin for four years now, but nobody in Vienna knows about that. And I’ve worked for streamers, but I never get feedback from that either, because it’s being streamed somewhere far away – in India or in Australia. So, you don’t get a response, or you just get numbers – “Oh! Cool! We’re doing well!”

I can’t really connect to my audience any more, other than by doing theatre. My last theatre experience was very good, Yerma directed by Simon Stone. [Yerma, directed by Stone in English, opened at the Young Vic in 2016 with Billie Piper playing the lead.]. We did the German version of it in Berlin. That was a wonderful experience. We started during the epidemic in 2021, and we were in repertory until July 2024. We had a really long run with a lot of sold-out shows and the audience was enthusiastic, very young people, crowded. The Schaubühne is a very nice venue for after the show, with its beautiful cafe and the little street where you can sit outside in the summer. A lot of the young audiences stayed and talked to us about what they saw. I totally enjoyed that. And the work of Simon Stone was really well received; it fit in to what people in Berlin want to see.

DR: “Yerma” – both Lorca’s original and Stone’s adaptation – is a poetic play which also has political resonance in terms of feminism.

CP: It’s also very dramatic – very funny, and also very sad. It’s not only a private thing – if you have kids or not. You’re tied to the community. You fit in or you don’t, and maybe it is not even your wish but the ambition that society has for you that counts. It seems to be realistic, but it’s not.

And in Stone’s production, there are a lot of things happening – even the stage design. The audience gets blown away by the stage effects [the entire play takes place behind a rectangle of glass walls with audience siting along the length of the stage on opposite sides.] It was something they’d never seen before.

DR: Rodrigo Francisco said when I interviewed him this year in Almada that he didn’t think anything has ever changed because somebody went to the theatre and saw a play about, say, climate change. It didn’t change their behaviour. That’s the opposite of Milo Rau’s approach, isn’t it?

CP: Exactly. His work is not meant to be a play or a show; it is a participation in political public life. He wasn’t doing that before. I think Milo radicalized himself during the pandemic, and also when becoming the Wiener Festwochen director. I’ve seen his old shows and they were still shows, in the way of documentary also, but they were still theatre. I think now he has expanded theatre into the pubic space and that is a very new concept. Here it is very unusual, and Rau is using a whole institution, everything the Wiener Festwochen has to offer. He is giving a public space to people who are able to express their opinions. This is new. I think in this part of the world, George Tabori did something similar, but he was outstanding and alone.

DR: Why did you join the Resistance Now! movement as a leader? Did Milo Rau contact you?

CP: I did not join the movement. I joined the Burgtheater. They chose Rau as the director for the next season, and I’m in his show. But now Jelinek’s play Burgtheater, the show that I’m assigned to be in, turns out to be a movement! So, I stumbled into it, but I didn’t stumble out of it once I got in. It wasn’t a movement when we met for the first time a couple of months ago; it was a show then. But now the political situation has changed, and Milo’s take on theatre has changed. I think what he is doing is very important. We are living in complicated times with fascism coming up again. Milo is right that we have to stand up and speak out loud at the moment. I really love doing normal theatre that just stays in the theatre, but I feel that right now it is not enough.

DR: And you know you have an audience, because of the popularity of the Wiener Festwochen 2024.

CP: He didn’t know that he had this audience either.

DR: I guess he realized the audience was there, after the mock trial of Austrian government officials that took place during the Wiener Festwochen weeks called “Die Wiener Prozesse” (“The Vienna Trials”), modelled after Rau’s Zurich, Moscow and Congo Trials where he establishes “a forum far removed from political trench warfare, in which a situation is … created where discussion becomes possible” ? That was extremely popular.

CP: Yes. He wanted to see what would happen, and the result was, OK we have to talk about this. A lot of young people really need this. We’re turning the clock backwards into fascism and antisemitism and xenophobia, and something has to happen here.

DR: But you still are producing the play “Burgtheater”?

CP: Yes, the other actors who are on the list as leaders of Resistance Now!, Mavie Hörbiger, Birgit Minichmayr and myself – we will be playing roles in Jelinek’s original Burgtheater play. There will be other actors from the Burgtheater participating, but they have not been appointed yet. Milo’s starting the casting now. We were already selected in May or June. We have some pre-rehearsals coming up but the actual rehearsals won’t be until March of 2025. But Milo Rau wanted to act now, because of the upcoming elections [29 September 2024]. He chose to name the actors, because actors are important in Vienna. It’s different in other places. In some parts of the world, the director or the playwright is the most important person in a theatre production. In London, stage managers can have a certain fame, and that is totally unheard of here in Vienna. Birgit and I have been with the Burgtheater for a very long time, and Mavie comes from the family that the play Burgtheater is about, and everyone in Vienna interested in theatre knows that.

DR: You weren’t involved in the 2024 Wiener Festwochen, were you?

CP: No, I was in Berlin still working at the Schaubühne at the time. I was doing spinne (spider), a monologue with Maja Zade on the AfD [German right-wing political party called Alternative für Deutschland.

DR: Are you aware of being German when you walk down the streets in Austria?

CP: I think I don’t walk around as a German but as a European. I’m really a great fan of the European Union. I totally believe in it and was very upset when the United Kingdom left it. In my opinion, Europe needs to be much stronger than the national governments. Everybody hates that idea. They want the national governments to be very strong and the European Union to be some small aspect of their lives. But I strongly believe the other way around. So, when I go around Vienna and talk to people about politics, I’m talking about politics in Germany as well.

DR: So, Rau’s Resistance Now! is actually a project with implications for all of Europe?

CP: Yes. Like Milo, I don’t want the right wing to get into power and change the laws. That is a danger in many European countries. There’s no way not to talk about politics right now! I’ve never lived like that before. That’s why it is a good take of Milo Rau to say, “Right now, that’s what we have to do!” Because that’s all there is right now.

DR: What do you think the role of art is in society?

CP: To express things for people who can’t express them. Whether you write a novel or paint a painting or act in a play, you give a voice to thoughts that aren’t being thought by everybody. That’s what the arts are for. But right now, everything turns into political GPSing: “Where are we? What do we do?” And of course, the arts go along with that. Everybody is just as confused, the artists as well. They aren’t outside society anymore and can’t show things to people who are busy with their daily lives. The purpose of art right now is very different than it usually is in my opinion. Art is to help and guide and to provide freedom of thought – and, like we are seeing, it does this differently at different times.

[Lead image here courtesy of Axel Hörhager.]