“Don Giovanni”, Opera Ballet Vlaanderen (OBV)

Dana Rufolo in Antwerp

★★★★☆

18 January 2026

The Opera Ballet Vlaanderen (OBV) version of Don Giovanni is above all dedicated to communicating the translucence of Mozart’s musical score in a staging that emphasizes that the opera is a dramma giocoso. Sensitively conducted by Francesco Corti, the symphonic orchestra renders the operatic melodies in resonant and clear tones. Corti demands modest restraint of his musicians, avoiding extremes of volume change and emotional intensity in favour of a continuity that integrates arias, duets, and ensembles and uses the harmonics of chromaticism less to prognosticate dark and evil forces than to reveal the complexity of the music.

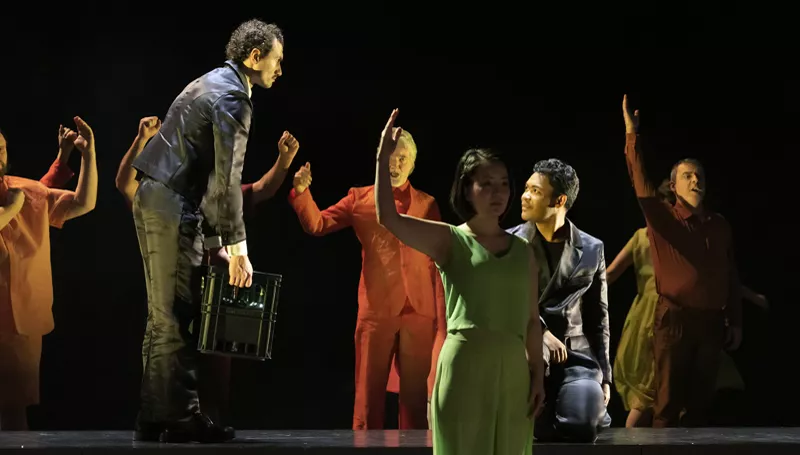

Photo credit: Annemie Augustijns.

Coti’s homage to Mozart is reflected in the mise-en-scène, intentionally. The conceptual vision behind this production is to emphasize the collectivity rather than to emphasize Don Giovannni’s singularity as an aberration. He is rather more a part of everyman, a manifestation of one of the extremes of human nature that otherwise resides, like statistics, principally in the center of a continuity; he is an outlier. The stage is peopled not just with Don Giovanni, his servant Leporello and the three women – Donna Anna, Donna Elvira and Zerlina (and their fiancés) whom he has wronged, but also with characters from the surrounding social environment. These are the choir of the OBV whose presence normalizes Don Giovanni and dampens the extreme emotions that, traditionally, Donna Elvira exhibits.

It is a Jungian interpretation, with the audience seeing archetypes instead of individuals. Traditionally, Elvira oscillates between an altruistic desire to warn against the philanderer and a deep affection for him despite herself (the programme notes suggest that she is a victim of “hempathy” or inordinate respect for a man of influence, a term coined by Kate Manne). Under the direction of Tom Goossens, Elvira (played by Alessia Panza) is chiefly of one mind, only briefly regretting that she feels sorry for Don Giovanni (according to the surtitles in English) at the beginning of Act Two.

There are no outward trappings to indicate class distinctions in this innovative Don Giovanni. Everyone in the ensemble onstage is dressed in pastel color-coordinated outfits. In the final scene they wear light beige costumes which in their neutrality belie social status (costumes designed by Sophie Klenk-Wulff). According to Lorenzo Da Ponte’s 1787 libretto, Don Giovanni is a cavalier, meaning a nobleman, and so his exploitation of Zerlina on her matrimonial night is usually seen as especially brutal, since she is a peasant as is her fiancé Masetto and therefore they are at a social disadvantage.

In Goossen’s unusual interpretation, the archetype of masculine sexuality exploiting female naiveté dominates. Don Giovanni represents a necessary scourge, tolerated like our contemporary dictators or would-be dictators as an inevitability. Referencing Freud, he is the Id come alive, pleasure-seeking and guiltless in his appetites. The baritone singer Michael Arivony plays this role with precise enunciation; a full-bodied rendering of the few arias he has are extremely confident. Increasingly seductive as the opera’s narrative progresses, he is also clownlike and vain, bounding about the stage like am imp with a devil-may-care attitude towards Leporello who scarcely interests him. In this way, Don Giovanni is untethered from its classical interpretation as the tale of a social psychopath who uses the power inherent in his social standing to take advantage of gullibility and innocence, instead emphasizing the dramma giocoso aspect to the opera.

To my mind, the definitive contemporary performance of Don Giovanni is the Italian one performed in 2011 in Milan at La Scala with Daniel Barenboim conducting and Robert Carsen directing; it is available to watch on YouTube. Giovanni’s (attempted?) rape of Anna is wordlessly staged at the commencement of Act One, just as she describes it in Act Two to her fiancé Don Ottavio. In this production, Elvira is an emotional wreck as she veers from anger to lust and pity. It is this kind of emotional extreme I reference when I talk about the “classical” modern interpretation.

The OBV’s production is symbolic and abstract, this is contrary to how the opera was staged in Milan.

Sammy Van den Heuvel designed the stark and symbolic set which is the key element used by Goossens supporting the prioritizing of Mozart’s composition and the archetypical nature of the characters. The stage design is composed of an abstract cross. The longitudinal direction is indicted by a sole ladder that stretches from the pit to the flies or, symbolically, from hell (where, flames leaping out, Don Giovanni will end up) to heaven, and upon which sporadically during the opera the dead father of Anna, the Commendatore slain by Don Giovanni, climbs (both down and up).

The vertical plain has to be fused in the minds of the audience members, as it is in no way directly associated with the ladder but is instead the raised platform – an elevated runway – stretching from left to right horizontally along the stage and upon which the choir and secondary characters, including a man herding a flock of chickens – tread.

The choir and principal singers themselves introduce angular lines of movement that radiate towards centre stage as they initially introduce themselves. Rather than turning their backs and walking off-stage as we are used to, they retro walk, giving the audience the impression that they are being pulled backwards offstage. This ties in to the director’s decision to make Act Two the inverse of Act One, with punishment meted out on the forsaken Don Giovanni ending the cycle that began with him meting out punishment.

Leporello in my opinion is the most difficult character to portray, because he voices disapproval of his master’s waywardness but never acts on his disapproval. Poverty alone, demonstrated when Michael Mofidian as Leporello comes obsequiously to Don Govanni to receive four ducats (a scene played very rapidly so as to reduce time for reflection in the OBV version), doesn’t explain his willing servitude. He is probably the least modern of all the characters in the Da Ponte libretto, but his aria listing the over 1,000 physical conquests of his master – using for his figures a paper rolled out the length of the runway – produced bursts of laughter in the audience.

In fact, Mofidian was a popular singer and character for the predominantly Flemish audience members. Like the entire cast of opera singers, his voice was appealing, clear, resonant but not extraordinarily overwhelming. This is in keeping with the emphasis on collectivity and on a midpoint as the source of balance – no stars allowed – in this unusual production. The one exception was the remarkable vocal range and emotional timbre of the tenor Emmanuel Tomljenovic singing the role of Don Ottavio. Although there was an ever so slight hesitation before he jumped octaves, his range was startling and poignant.

A final observation: the choir executed movements of the hands, arms and legs that resemble the rythmiques movements developed by Emile Jaques-Dalcroze. This dancing technique was developed to give musicians and singers a feel for the flow of the music by converting the length of a note or of a passage into movements that are simple to execute and which are like the beats of the conductor’s baton, matching the melody and rhythm. Again, the employment of rythmiques in this performance reinforces the interpretation supported by both the conductor and the director that the OBV’s is, above all, a performance devoted to music and word and only secondarily to theatricality.