The Critic, film by Anand Tucker and Patrick Marber

Simon Jenner reviews film based on the novel Curtain Call by Anthony Quinn

January 2025

1934. Theatre critic James or Jimmy Erskine (Ian McKellen) and actress Nina Land (Gemma Arterton) whom he’s long criticised, are both facing the abyss. Patrick Marber’s dark theatrical thriller adapted from Quinn’s 2015 novel is directed by Anand Tucker.

It’s certainly a familiar world. If Matthew Bourne can adapt novelist and dramatist Patrick Hamilton in his ballet The Midnight Bell, Marber and Quinn certainly have no trouble invoking him in both fiction and theatre (as well as films of his plays), where Hamilton thrived. The difference is glamour. Here an often seedy 1930s world is mostly banished to the lifting of a pork chop. Or once a chipped window frame dripping with rain.

Erskine, a brilliant but waspish critic, has worked for The Chronicle for over 40 years. He and other old-guard journalists are told to watch their backs as the new proprietor, the founder’s son Viscount David Brooke (Mark Strong) is out to streamline. Erskine thinks he’s safe.

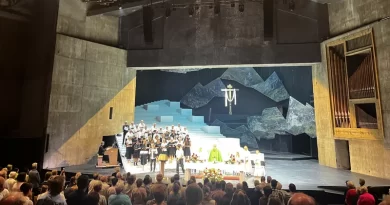

Attending a production of The White Devil Erskine is about to strike again. Land in the title role complains that Erskine has loathed her performances for ten years. Hardly surprisingly: “Her death is akin to a deflated dirigible” he concludes, invoking the burning R101. Marber and Quinn have though erected a series of word balloons that do anything but deflate, and they are studded throughout the sparkling dialogue.

McKellen is as you might expect in this role, as delightful as 91% chocolate dosed with sea-salt. He revels in his waspish coating (in Peru, chocolate-covered wasps were considered a delicacy). Particularly impressive is his movement from rancour and disdain to confiding warmth that then opens into a bottomless need for something else. He recognizes the need for danger, the risk he once found briefly in acting, but is now fixated on pushing his sexuality to provoke society and above all, the law. Continually he’s warned by colleagues desperately pulling strings, or in a sense, Erskine’s stings from an easily punctured public and police. The flipside to a delight in danger is how to react when discovery and disgrace is certain. McKellen makes the devilish appealing then appalling. If there is a level I’m faintly troubled with it has nothing to do with McKellen’s performance.

In a revealing vignette Erskine has to deal with Brooke’s wife Mary (a flailing, infuriating Claire Skinner), who talks of preferring The White Devil to “his other … The Duchess of Malta.” Erskine’s incensed and demands the management get rid of her. Then the killer review his sub-editor pleads with him to tone down. You sense Erskine’s oblivious to Brooke’s plans, not least his fear that Erskine will arouse homophobia. Jokes about the fascist Mail abound (it’s a year before “Hooray for the Blackshirts” would blacken its ebony reputation). It’s not long either before we meet some of Mosley’s Blackshirts. Meanwhile, Land ends her off-on relationship with Brooke’s married son-in-law Stephen Wyley (Ben Barnes). Again.

Sumptuously lit and shot by David Higgs and John Gilbert, edited by Beverley Mills and designed by Lucienne Suren, The Critic delivers a tight luxury with Deco glamour against the glimmer of footlights and occasional grime of everyday life. Claire Finlay-Thompson very slightly modernises the straight-down flow of Deco dresses, and the most dazzling are day-dresses, occasionally flung in a matter of a few frames against the voluminous peach silks of costume. Craig Armstrong’s music is moody and curiously redemptive.

The Critic is deceptively fast-paced though it seems leisurely. We segue between Erskine and Land, subject of his wrath. Even Land’s mother Annabel (Lesley Manville) felt she was too florid with her hands and her best act was her look. She tries too hard. And she counsels Land to land the critic. “Talk to him.” A line has been crossed. And when Land does, she finds his weakness, and confesses hers. “There is art in you Miss Land. My disappointment is in your failure to access it.” When Erskine gets to his offices, old colleagues are saying “Finita la comedia.” Everyone’s being axed. Erskine is heedlessly hedonistic and cruel. Caught with his secretary – Alfred Enoch as the awakening conscience Tom Turner – The Chronicle gets him off the hook but he’s out.

It’s striking that Land’s mother is on the money. Land indeed tries too hard. And when Land visits Erskine over her failure to act Olivia in rehearsals for Twelfth Night, he begins to give her a masterclass. And it works, surprising those who knew Erskine’s previous views. Discussing Land with her admirer Brooke at his farewell dinner, the latter is wrong-footed by Erskine’s praise.

But there’s a price. And Brooke and Land are forced into a Faustian pact. Decent, compassionate, class-guilty Brooke (this sits oddly with his axing jobs) isn’t even allowed the illusion of love. Especially when Wyley confesses his part to his father-in-law. Strong writhes like a butterfly impaled on his own delicacy and tact. After this it becomes as positively Websterian as that opening play. More The White Devil than Twelfth Night.

Strong performances from Ron Cook as fellow (opera) critic Hugh Morris fallen on hard times (and happy to eat Erskine’s untouched chop), Romola Garai as Stephen’s knowing wife Cora (Brooke’s daughter), whom it would have been enjoyable to see more of, with her bitter anti-Semitic line: “I should never have married a Jew!” Enoch too in an exchange with Garai as new owner of The Chronicle turns in one of the most charged moments.

Ferdy Harwood (Nikesh Patel), and Rebecca Gethings as dresser Joan Harris etch in characters: Harris reading notices and raising eyebrows watchfully, flickers for a moment in dressing-room lights. Marber and Tucker are generous with brief spotlighting. Manville’s last appearance glows with bleak humanity and pathos in dialogue with Barnes. Cameo performances by RSC luminaries such as Jasper Britton flit across and are gone.

I’ve not read the novel. But this is a screenplay reanimating the speed and cut of its model: the Jacobean play we see at the beginning, period productions neatly skewered in lighting and sparse sets. Most of all though I’m reminded of Patrick Hamilton. Whilst The Critic can’t rival Hamilton’s Rope and Gaslight for an almost classical tautness, and stretches improbability a little, it’s still gripping. Most of all it takes to new levels the co-dependence that can poison an actor and their appraisers. L. P. Hartley’s The Shrimp and the Anemone comes to mind too. That a work can evoke such responses says much. You might not quite feel it’s inevitable. Nevertheless as fable it seethes.