“The Other Place” at Lyttelton, National Theatre

Jane Edwardes on the South Bank

13 October 2024

Playwright Alexander Zeldin is best known for The Inequalities trilogy of plays – Beyond Caring, LOVE, and Faith, Hope and Charity – empathetically focussing on those living on the edge of society, while The Confessions was inspired by the life of his mother. All have been staged at the National Theatre. At the Lyttelton, he explores very different territory in his new work The Other Place, with its subtitle of ‘after Antigone’, the play written by Sophocles in 441 bc.

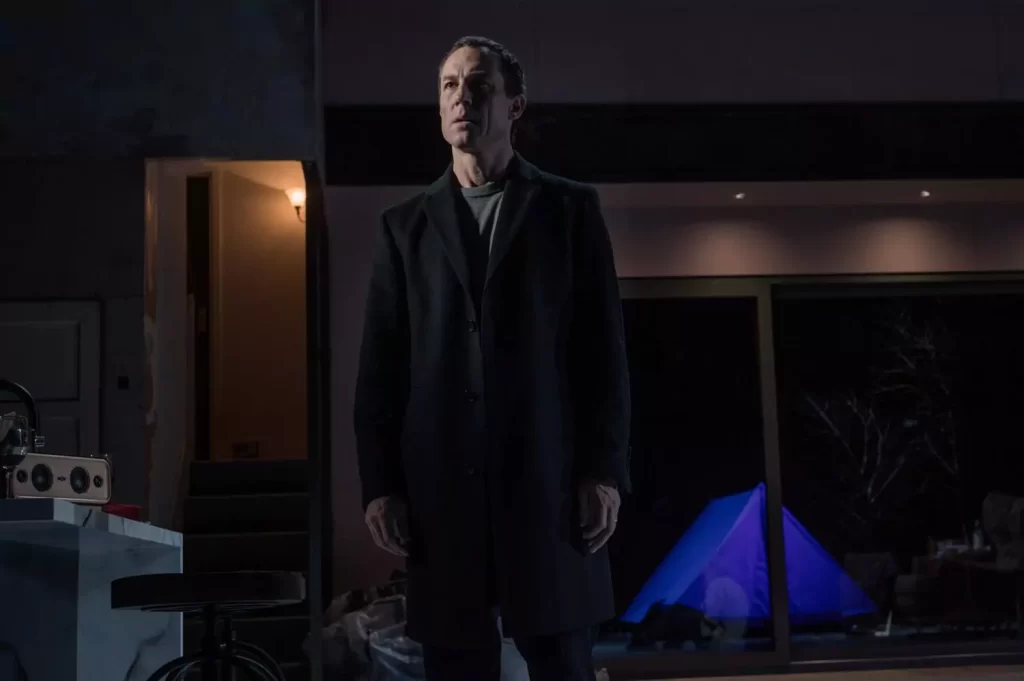

Tobias Menzies as Chris.

Photo credit: Sarah Lee.

While a knowledge of Sophocles’ tragedy is not essential, it does add interest. Zeldin is not the first playwright to be inspired by Antigone. In the past, Racine, Jean Anouilh, and Athol Fugard have all produced their own versions, the last two inspired by Antigone’s bloody-minded resistance to an abusive authority.

In Sophocles’ play, Antigone’s brothers Polynices and Eteocles have killed each other fighting in a civil war for the throne of Thebes. The new ruler Creon, Antigone’s uncle, has resolved to honour the latter and shame the former, leaving Polynices unburied outside the city walls at the mercy of the birds and the beasts. The mourning Antigone determines otherwise, even if her efforts result in her own death.

Zeldin is far freer with the original material than his predecessors. There are no rulers, rather his play is set among a modern, middle-class blended family. But he does stick to the Aristotelian rules of unity of time, place, and action. Annie is grieving for her father and at loggerheads with her uncle Chris, who is determined to scatter his brother’s ashes, a man, he claims, who poisoned everything. She is equally determined that the ashes should remain in the house, where her father lived and where she still feels his presence.

Zeldin’s dialogue is very naturalistic and the opportunity to fill the audience in on the back story is consequently limited. There are difficult gaps in our understanding. In particular, it’s not entirely clear how long ago the unnamed father committed suicide in the garden; nor why Chris has inherited the house rather than the two daughters. What happened to their mother? Apparently, Izzy, Annie’s sister, now in her 20s, was so young when her father died that she remembers little about him. If that is the case, Annie’s grief has lasted well over a decade, which makes its continuing intensity surprising.

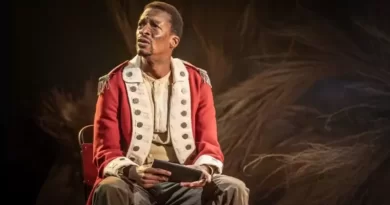

Jerry Killick as Terry.

Photo credit: Sarah Lee.

Understandably, Chris and his wife Erica want to put the past behind them and make the house their own. Helped by Terry, a project manager and friend, Erica is fully engaged in making improvements, including the addition of vast French windows to let the light in. Little does she realize how many secrets there are to expose. Rosanna Vize’s kitchen set is not only dominated by these windows, but also by a vast and sometimes annoying skylight.

At the start of this intense 90-minute play, the family – Chris, Erica, her son Leni, and Issy –plus Terry, are waiting with some trepidation for Annie to arrive for the ceremonial scattering of the ashes. They anticipate that her presence will be problematic. She has apparently been drifting around the country and has inherited her father’s mental health problems. Her arrival doesn’t disappoint. Emma D’Arcy’s Annie has no time for niceties. She’s a troubled, still figure. Flickers of pain cross her face as she views the changes to the house and her eyes are drawn to the urn with her father’s ashes. Her speech may be slow, but she is resolute. Encouraged to “move on”, she makes it clear that that is not on her agenda.

The ashes are tugged this way and that, vulnerable to being spilt all over the stage, which threatens to turn tragedy into face. The ceremony turns out to be a fiasco leading to a fierce and ultimately unexpected confrontation between Annie and Tobias Menzies’ Chris in the middle of the night. While D’Arcy holds her ground, Menzies is unable to keep still, a jittery presence who threatens violence. As the past catches up with them, Yannis Philippakis’s menacing music adds to the tension.

The entire cast, under Zeldin’s direction, is outstanding. Alongside D’Arcy and Menzies, Alison Oliver is excellent as Issy, the more compliant sister, who hates confrontation and lives in the house for the want of anywhere better to go. Nina Sosanya’s Erica refuses to confront reality and buries herself in domesticity; Lee Braithwaite as her kindly son finds the adults’ behaviour inexplicable. And Jerry Killick is Terry, the project manager, in flip-flops and shorts, who stalks the room and doesn’t hold back on his opinions however misguided. His unwanted attempt to kiss Issy foretells what is to come.

A shocking revelation provoked gasps from the audience. Is it convincing? Not really. We are left too much in the dark. The ending too, without giving anything away, lacks the inevitability of Sophocles’ Antigone. After a compelling start, Zeldin’s play teeters towards melodrama, only the superb acting prevents it from tottering over the edge.