“Redlands” at Chichester Festival Theatre

Simon Jenner in West Sussex

8 October 2024

“Hello. Hi. You don’t know me yet … but my name is Nigel Havers.” A 16-year-old boy stands on a light-blazed promontory and talks to us, nervously. He’s about to go on this very stage as Puck in a school play. It’s a singular way into “the trial of the century” taking place nearby at Chichester Crown Court in 1967, with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards accused of drug possession. That father Michael Havers QC presides over it is no excuse. There are though other connections. And quite a lot of music. Charlotte Jones’ Redlands runs at Chichester Festival Theatre until October 18 under the direction of Justin Audibert.

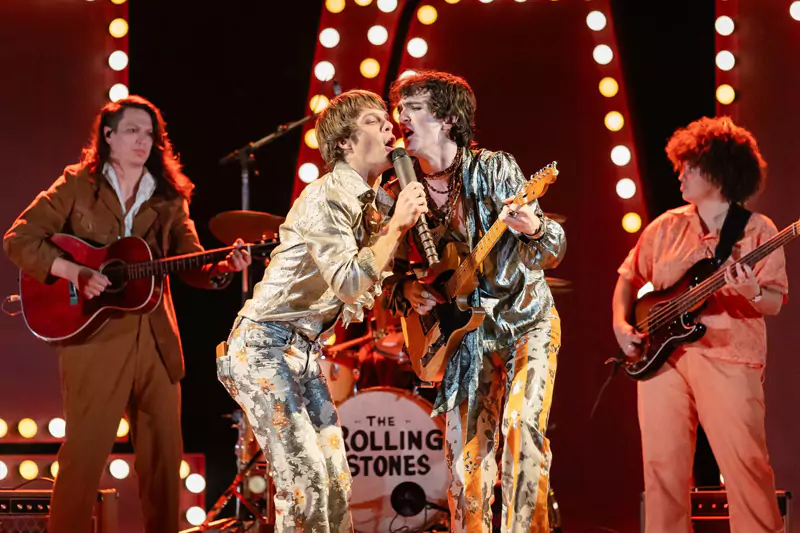

Jasper Talbot and Brenock O’Connor.

Photo credit: Ikin Yum.

Three elements mark this hybrid, where the title is taken from Keith Richards’ tucked-away West Wittering mansion. What grips immediately is the sound of fourth walls splintering all around the auditorium, as bumptious Michael interrupts both audience and play finding his seat, actors rush everywhere and platforms with gyrating Jagger thrust themselves into the front row. A Chichester reference drops every few minutes with an importuning clang, when the audience often erupt. Indeed, the Festival has rarely been so lively. If June 1967 was the only time Chichester was hip, this is determinedly the second.

The next fusion takes time to settle. A play spanning the conflict of aspiring actor Nigel with his father and balancing a toehold in a world of pop stars on trial, it seems at first two separate plays as the narrative shuttles between them. From school to Redlands raid with the police determinedly waiting until George Harrison is out of the way touches not so much on sensation as revenge conspiracy.

With such an auditory buzz by now one might miss Jones’ seriousness here. It needs flagging with a photographer lurking in the bushes, as one Derek Carter (Adam Young being egregious and insolent) of The News of the World photography team does. As for Richards, Jagger, and Marianne Faithful they see it differently at first. “What should we do about the Fairies?” asks Keith. “It’s cold out there, Keith.” ”Oh, yes, they must be frozen, poor little things.” Jones’ gift for comic insolence winks everywhere.

Jones, known for plays like Airswimming, her first from 1998, and multiple-award-winning Humble Boy (2001) revived in 2018, the same year as Meetings was premiered at Chichester, is no stranger to music. She wrote the book for Lloyd-Webber’s The Woman in White in 2004. Her 2011 The Diva in Me charted her friend, actress and extraordinary vocal mimic Philippa Stanton singing her way to individuality.

Music occasions phenomenal performances here. But as Airswimming and supremely Humble Boy show, Jones’ gift for breathtaking intimate symmetries are challenged by her talent for bustling ensemble pieces. Here, she revels in the latter but finds the finest moments in Redlands as deft synchronicity, mainly in Act Two where the loud set-ups pay off. One is particularly moving.

Louis Landau (foreground) as Nigel Havers.

Photo credit: Ikin Yum.

Anthony Calf excels as Michael Havers, never missing a beat as a carapace of success, till his inner vulnerability breaks in. It was long identified by his father Cecil (a sparkling and beautifully modulated Clive Francis), himself a reluctant hanging judge over Ruth Ellis. Cecil or ‘Bongo’ confides this to Nigel who in the course of a cricket match never quite gets ‘Bongo’ to see that he, unlike elder bother Philip (Young in fleeting varsity flannels) and three generations of Havers, will never be a lawyer.

Louis Landau makes a superb stage debut as winsome, flustered but ultimately determined Nigel. Nigel’s also aided by mother Carol (Olivia Poulet) who lends not only warmth but leads a quiet, trenchant and witty revolution in the home where she bursts her trad-wife expectations.

More momentous is Nigel’s encounter with Marianne. Emer McDaid also excels as singer, in “This Little Bird”, and in the finest set-piece solo “As Tears Go By”, the first hit written by Jagger and Richards, delivered as Calf reclines in stupor to a waft of dry ice. McDaid too delivers Marianne’s palpable exclusion from any serious concerns with dignity, outrage and affect: from deselection as trial witness (Michael’s doing) through macho photographer Terry (Young again) with Nigel present. Decked out by her in new clothes to Michael’s outrage, Nigel undergoes every kind of education but the obvious. Their touching relationship spans the play like an iridescent filament: butterflies and wheels come to mind.

Though initially tugging the narrative untill it asserts its own momentum, performances of Jasper Talbot also making his stage debut as Mick mesmerise. It’s not simply the physical resemblance, but the way Talbot both makes Jagger’s voice his own, with a kick of individuality; above all the chemistry with Brenock O’Connor playing Keith Richards. Their duetting blazes across Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away”, standards like “Can I Get a Witness”, “Mercy, Mercy”, and Stones originals “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction”, “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” and in this work the valedictory “Ruby Tuesday”.

Talbot though sashays cheerfully between LSE-educated RP and mockney: a model of insouciance with a downturned mouth formed for irony. O’Connor burnishing Keith’s slightly out-of-control persona with a wire brush, drops tactical aitches and H bombs where Mick knows how to modulate. Credit to Ben Furey’s canny voice coaching here. Their exchanges make for an infectious comedy of its own. Such dialogue and performances almost obviate Jones’ feat of nudging the Stones to the side of their own story, as she follows the Havers.

It needs bridges. Cue Ben Caplan’s Stones manager Allen Klein, seeking out Michael, not taking “no”, not taking “guilty” and energising every scene, playing off his skewed sense of the British class system with blowtorch delicacy occasionally fine-tuned to acetylene.

For a work spanning three hours, opportunities are lost. Women’s roles, unusually for Jones, are often underwritten. Ella Tekere is at least vocal in a run of small parts including student protester or journalist; though Lara Rose McCabe, as Frieda and a dancer (Shannelle ‘Tali’ Fergus delivers solid period choreography) might have had more interactions with McDaid’s Marianne.

Elsewhere Sam Pay harrumphs caricature through CI Bramley and Judge Block, with a brief reprieve as kindly RADA principal where he gives Nigel immortal advice. Riley Woodford’s parts might have been elided with Young’s. Jones aims at epic scale, but fewer small parts, and those remaining built up in those deft touches Jones is so good at, might have knit the work tighter.

Ryan Dawson Laight draws bolts of wondrous fabric for costumes. Set by Joanna Scotcher signals ‘Chambers’ in lights and the words ‘Redlands’ in bulbs. There is a Battenberg of faded carpets. Initial fun with lampshades representing two things at once gives on to effective semaphores with trolleys, desks or armchairs. Matt Daw lights subtly where he can. Composer Benjamin Kwasi Burrell remodels hits (with Alan Berry directing the music) and crafts a time capsule where Claire Windsor’s sound never overwhelms.

Act Two does land this drama with the right touch, and Jones’ alchemy of one speech given simultaneously shows why any Jones play is worth travelling for. And this is joyful: rarely has the festival been so lit up beyond the garish lettering or garnered such applause. Deeper Jones themes touched on, like mental distress and confusion, figure fleetingly. It’s not that Jones has written two plays, as not drawn them together with that tough iridescence marking her very finest work.