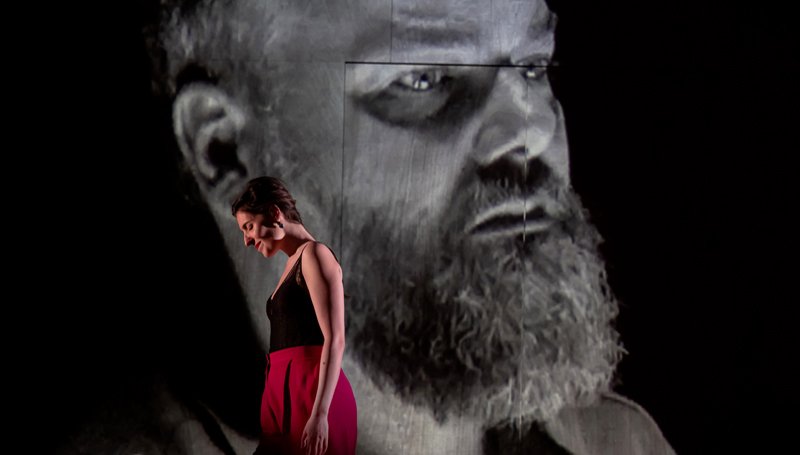

“The Carmen Case”, Grand Théâtre, Luxembourg

Dana Rufolo

The most brilliant, dramatic and beautiful performance I have had the privilege to see in a long time is the new opera The Carmen Case. It is finally a drama of aesthetic integrity that introduces us to the collective dream we all share that the twenty-first century which began in horror will mutate into a period of renewed enlightenment. When such a work of art is produced, then we can hope.

Photo credit: Pascal Gely.

I saw The Carmen Case on 11 January, straight from Paris, written and directed by librettist Alexandra Lacroix with music from The United Instruments of Lucilin, composed and conducted by Diana Soh.

Fusion of George Bizet’s 1875 Carmen with Lacroix’s original libretto that references contemporary legal practices with the intent of challenging biases about gender and sexuality results in a transcendent work. Its story and catchy tunes are offset by an intelligent mise-en-scène that asks why so many women become victims of “passion” murders.

Photo credit: Pascal Gely.

The Carmen Case is a French production, so Lacroix looked at the statistics of her country: every four days in France, a woman is murdered by a lover, husband or ex-partner. Her opera is set as an assize court where José is put on trial. We witness how José presumes that Carmen belongs to him, and therefore he has the right to kill her if she tries to leave him. Because Carmen never becomes the plaintiff in Lacroix’s libretto, José’s assumption is explored without any overt accusation of guilt. Scenes from Bizet’s Carmen using a second José, Xavier de Lignerolles (since José as the defendant is not free to leave the dock), are re-enacted so as to prove the facts before the jury, who are in effect us, the audience members. We see the evidence ourselves; there is no propaganda, no anger, we are not pushed into denouncing femicide, but we all understand the injustice and inhumanity of ‘passion’ murders because of what we witness. I have never seen a more convincing refutation of the general assumption that such murders are an inevitable consequence of human nature.

The rectangular stage of the Studio space at the Grand Théâtre has no elevation and no proscenium, so the orchestra, The United Instruments of Lucilin, was seated on the floor directly in front of the steeply raked audience seating, with Lucie Leguay conducting Soh’s score from stage centre. The wind instruments are on the audience’s left, and the strings, percussion instruments and sonically suggestive instruments like the udu, waldteufel and waterphone are on the right.

Characters appear for short scenes on the downstage area immediately behind the orchestra. Most notable are the experts in psychiatry and legal parlance who farcically display their erudition which loops endlessly around its own codewords, prejudices and assumptions.

A set of wooden stairs four treads deep and running the entire length of the stage connects downstage to a middle stage platform; the stairs angle forward at both ends so as to contain the action.

Photo credit: Pascal Gely.

The platform to which the stairs lead is the one we focus on the most. On the left we see José being tried for the murder of Carmen, locked within a dock – a wooden box on the left. Lawyers and advocates for an examination of the criminality of the crime are located on the right.

Behind this middle platform is an additional elevation with a rear door from which characters make their appearances. Above that, and well to the rear, a screen hangs; this is used to project images mostly of the state prosecutor (William Shelton) who never turns towards us as his face is constantly visible on the rear stage screen.

The reason I am providing an elaborate description of the Palladian nature of the stage structures is because the intention is clearly to stress balance and parity. The stage is organized to reiterate the opera’s carefully weighing of the artistic past of Carmen with the pressing contemporary need for enlightenment. From the opening scene where men are watching and discussing their reactions to a TV show about violence against women on the uppermost stage space to the closing scene midway and stage centre where Carmen is stabbed, the spaces in which the actions occur point out the logical underpinning to Lacroix’s argument against femicide.

The score, including favourite melodies like the Toreador song and Habanera (“L’amour est un oiseau rebelle” or “Love is a rebellious bird”) faithfully reproduced and sung to sweet perfection, is interpreted either traditionally or gutturally and even savagely depending on which instruments the United Instruments of Lucilin employ. Not only are all the actors excellent singers, but also their characters are richly developed. Micaëla (Angèle Chemin) in particular is remarkable with her wedding dress costume (signed Olga Karpinsky) and her unbearable emotional distress which involves her touching parts of her body spasmodically, visually reinforcing the depth of her love for José, the boy from her village she knows to be a “good man”.

Carmen herself is raw and insensitively brusque – even more so than is usual for the character in Bizet’s opera. Time and again, she shoves José to the ground in anger during the climactic scene where she insists that she does not love him at all any longer. She is no angel, and yet José carries a concealed knife, and his murder is absolutely unjustified.

Photo credit: Pascal Gely.

Unjustified is the most appropriate word I can muster, although it is inadequate, because there is no hint – no subtext – of justification in this scenario which looks with steely eyes on the infraction. We are allowed to visualize the dilemma of a woman who repels her former lover with less than bourgeois breeding and yet whose life nonetheless is sacrosanct. In the name of a ‘crime of passion’, a human life has been forfeited when reason, not outrage, needs to bear the weight of love and hate in our era.

Finally, not only are we brought to understand the need to legally protect women who are treated as chattels, but also we understand why Bizet conceived the heroine Carmen as a mezzo-soprano rather than a soprano, already breaking radically with operatic practice one and a half centuries ago.

Hence, we are given visual and auditory support for the idea that “on the one hand” and “on the other hand” – left and right. ‘Look,’ the cast led by Lacroix and Soh are singing, ‘Look for yourselves. Reject nothing blindly. Look at both sides of the story. Look at the past and the present, side by side.’ Every one of the resources of dramatic art is put into service of the opera as conceived by Bizet and placed in a modern context by Lacroix.

Beautifully, The Carmen Case brings to mind classical concepts from the age of theatrical invention of the early twentieth century, specifically the Gesamtkunstwerk, an ideal where all the elements of a performance fuse: voice, music, scenography. And the rhythms and flow of movement, the use of stage height and depth and stairs as architectural units is reminiscent of the work of the stage architect Adolphe Appia who facilitated the rhythmics of Jacques Dalcroze.