“1776”, American Airlines Theatre, New York

Glenda Frank on Broadway

6 October 2022

Some directors take a minute or two but from the first, Diane Paulus (with co-director and choreographer Jeffrey L. Page) plunge us into the heart of this declaration of independence: an ironic, distaff revival of 1776, the musical by Sherman Edwards (music and lyrics) and Peter Stone (book) about the Second Continental Congress as it debated its way to the 1776 Declaration of Independence. Paulus, whose credits include a circus Pippin (2013 Tony for Best Revival and four Drama Desk awards) and an all-woman Cirque du Soleil Amaluna in 2014, has a knack for jolting us into new worlds within the old and familiar. When creating a disco staging of A Midsummer Night’s Dream she opted for the title The Donkey Show.

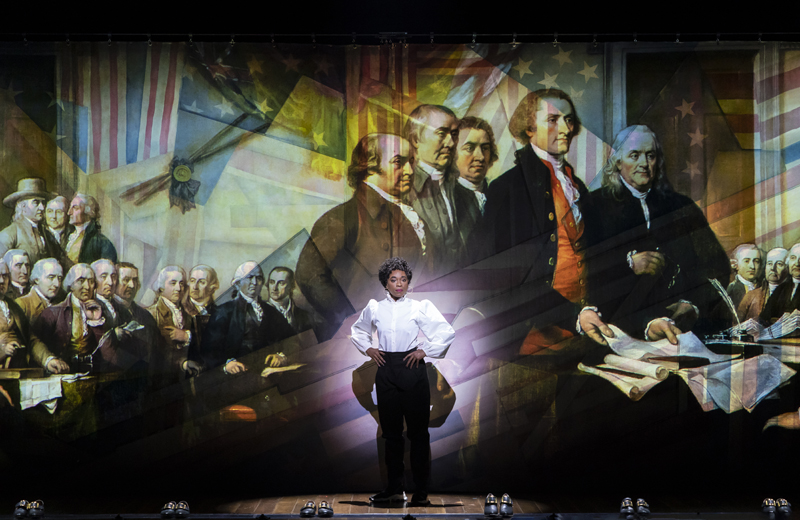

Kristolyn Lloyd as John Adams.

Photo credit: Joan Marcus.

This 1776 at Roundabout’s American Airlines Theatre on Broadway begins in front of an oversized representation of John Trumbull’s painting “The Declaration of Independence.” Actor Crystal Lucas-Perry (replaced on the night I attended by Kristolyn Lloyd) wears casual slacks and sets a light cynical tone with John Adams’ quip about his fellow colonists: “I have come to the conclusion that one useless man is a disgrace, that two become a law firm, and that three or more become a congress.” At the premiere in 1969, the barb was in the word “useless.” In 2022, the joke is in “men.” Women, the LBGQT community and people of colour are fully present, singing, dancing, and acting up a storm. Diane Paulus said that “Every single person on that stage is someone who would not have been allowed to be inside Independence Hall in 1776.”

And while we are laughing – at the word “useless” or “men” – the curtain rises and Lucas-Perry (or Lloyd) is joined by other women, of all shapes, sizes and ethnicities with many in sneakers. It could be the Saturday check-out lines at a budget supermarket until the air fills with colour as the actors twirl into eighteenth-century period jackets. And then they roll their white socks high until their slacks become breeches. Slipping into period footwear (walking a mile in the shoes of the founders), they are at once our contemporaries while also being John Hancock, Robert Livingston, Richard Henry – the signers of the Declaration of Independence – arguing how to create a new nation. It is pure Brechtian theatrics, bouncing us between the sensibilities of two centuries as we hear the famous arguments with both historical and contemporary ears. This jockeying stimulates the imagination. Paulus and Page have added a magnificent subtext to an old story, a nation still in dialogue with itself. For respite, we have the muscular score and lyrics (orchestration by John Clancy) and those gorgeous voices.

Elizabeth A. Davis, Patrena Murray and Kristolyn Lloyd.

Photo credit: Joan Marcus.

Amid the serious debates, two comic leitmotifs are introduced: John Adams (Lucas-Perry or Lloyd), an outspoken leader, is an irritant. “Sit down, John!” the company sings, and minor issues such as recompense for a dead mule (“Piddle, Twiddle, and Resolve” sing Adams and company) are mixed with the creation of a prescient anomaly, an eighteenth-century democracy. Ben Franklin at 70, the oldest delegate who frequently naps in the July heat, is played by Patrena Murray who looks like a short Whoopi Goldberg, an evocation of the wise woman. Adams and Franklin, tasked with heading the committee to write the declaration, recognize the political need for a gifted Southerner to balance the Northern majority and so they enlist a reluctant Thomas Jefferson. As played by a very pregnant Elizabeth A. Davis, he is a taciturn bookworm, moping for his new bride. When they send to Virginia for Martha to cure his writer’s block, the musical adds romantic comedy. The lovely Eryn LeCroy (clad in a stylish wedding cake dress) and Jefferson sequester for days. It’s light, funny and very sexy as she confesses – in “He Plays the Violin” – that the secret of their passion is his bow work. John and his wife, Abigail (Allyson Kaye Daniel), sing “Yours, Yours, Yours.”

Gender-neutral casting works only when the actors and director remain gender-blind. 1776 is not a drag show, as one New York critic complained, perhaps longing for some RuPaul moments. Crotch-scratching, splayed-leg sitting, manly strides – which I have seen in other gender-neutral plays – take audiences in the wrong direction. This production has a point to make.

Act I sets the scene; Act II explodes. Jefferson and the committee, besotted with Enlightenment idealism, create a document that would have changed American history. But it’s a draft, and the representative raise many objections, especially to the sections addressing slavery. Sara Porkalob, as Edward Rutledge, the representative from South Carolina, belts out a show-stopping “Molasses to Rum,” attacking the northern coalition for its hypocrisy. “Molasses to Rum to slaves/ Oh, what a beautiful waltz/ You dance with us, we dance with you/ In molasses and rum and slaves.// Who sail the ships out of Boston?/ Laden with bibles and rum/ Who drinks a toast/ To the Ivory Coast?/”Hail Africa, the slavers have come!” Threatening to withdraw and kill the revolution, we watch the Southern delegation win.

The ensemble.

Photo credit: Joan Marcus.

In contrast with the noisy high energy of other numbers, “Momma Look Sharp” is a quiet showstopper. An impressive, understated Imani Pearl Williams, standing in for Salome B. Smith, plays a self-effacing courier from General George Washington, delivering mostly depressing news. Gradually the messenger becomes a presence and then the emblem of all the dying soldiers as Williams sings the slow, deeply affecting ballad. Usually, the dead soldier stands alone. By adding a chorus of black-garbed women, the directors extend the visual to include the mothers, evoking memories of women from many countries grieving lost children.

Carolee Carmello (“Cool, Cool, Considerate Men”) as the outspoken John Dickinson, who refused to sign the Declaration, was also a standout. There was so much talent on one stage – Lucas-Perry (at other dates in the run), Murray – and many with key moments in the spotlight. Jill Vallery, in the small role of Caesar Rodney, the delegate from Delaware who was suffering from cancer, was deeply affecting. As was Joanna Glushak playing the genially inebriated Stephen Hopkins, the delegate from Rhode Island.

There were problems. Costumes by Emilio Sosa called unnecessary attention to themselves and to the physiques of some of the women. I usually admire Scott Pask’s sets, but the nondescript benches and the benches upon benches didn’t seem a complementary visual or an aid to the choreography. Projections of national turmoil were jarringly academic for a night of rousing theatre.

Some people find the comparison to Miranda’s Hamilton useful, but Paulus and Page’s 1776 brings a different perspective. It’s unsettling to watch people of colour debate slavery (and evoke a slave auction), but it bounces the question back to all of us: what would we have done, even knowing the consequences?