“White Noise”, Bridge Theatre

Alice Grahame on the South Bank

13 October 2021

The American playwright Suzan-Lori Parks has built up an impressive body of work over more than three decades, including becoming the first black woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for Drama (for Topdog/Underdog in 2002). But despite her reputation stateside, her plays have not often been performed in the UK. Now, however, her most recent play White Noise (which won an Obie Award when it was first staged in New York in 2019) has received its European premiere at the Bridge Theatre in London.

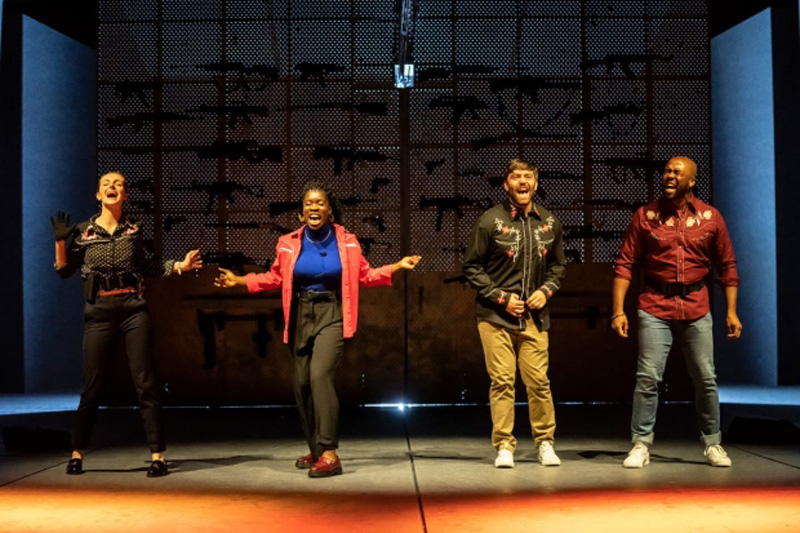

The ensemble.

Photo credit: Johan Persson.

White Noise is a bold and intense drama about four old college friends now in their thirties who form two interracial couples. It deals with issues of race, class, and “wokeness”. It asks awkward questions around whether we can ever be free of racist social structures. It is a deep dive into some timely and difficult conversations. Since the killing of George Floyd last year and the ensuing Black Lives Matter protests in major cities around the world its themes have become even more relevant.

The play begins with black artist Leo (played convincingly by Ken Nwosu) in the therapist’s chair, and the story is mostly from his perspective. His best friend Ralph (James Corrigan), who is white, gives him a white noise machine to help with his insomnia, but although Leo is sleeping better he can’t get the sound out of his head and it impairs his creativity. The white noise is a suitable metaphor for his worries and the dislocation he feels within the social world he inhabits. He lives in a comfortable apartment and has a stable relationship with white human rights lawyer Dawn, (Helena Wilson) but worries about the fragile basis of this lifestyle.

His worries are confirmed when he is beaten up by the police, for no apparent reason other than his race. In order to confront how he is treated as a black man in today’s USA, and to explore the continuing existence of racism since the days of slavery, Leo initiates a slave/master relationship with Ralph that must last for 40 days. The reasoning behind this controversial experiment is the notion that as a free black man not owned by anyone he is vulnerable, but as a slave he has some protection since the authorities will be reluctant to harm a white man’s property.

Ralph is initially horrified by the idea, but he accepts the challenge and gradually begins to enjoy his privilege so much so that he can’t relinquish it. He quickly descends from amiable liberal to a brutal sadist, locking his best friend into a metal collar and joining an underground white supremacist club. To make matters worse, due to an inheritance, Ralph is the owner of a shooting range.

Ken Nwosu as Leo.

Photo credit: Johan Persson.

As unlikely as it seems, the four protagonists hang out there, firing pistols at targets for relaxation. With this thought in our minds, the knowledge that the tension could quickly turn into deadly violence is a constant worry. The shooting practice seems so apt that it was a surprise to read in the programme notes that in the original American version the final gathering took place not in a shooting range but in a bowling alley. This setting explains the unusually elongated set. Designed by Lizzie Clachan, the staging had the audience at the narrow end of a long rectangle, giving an unusual perspective. At the start we see Leo in the foreground, and in the distance a bedroom which later becomes the focus for earnest reflections on his relationship.

With only four characters on stage, each actor has to work hard to make their characters real people rather than representatives of political or social positions. None are easy to like as they are mostly self-absorbed, but under Polly Findlay’s direction they all make a strong case for their own particular viewpoint. Each character is given the opportunity to step into the spotlight and have their say.

Despite its serious subject, the script is peppered with humour that references discussions around critical race theory and white privilege. For example, Ralph’s black girlfriend Misha (Faith Omole) is preoccupied with producing a social media phone-in for her online show called Ask a Black, in which she answers questions from the public while assuming a hammed-up stereotypical persona. We leave the theatre feeling White Noise has delivered a provocative premise that has raised acute questions about race and the legacy of slavery that are timely.