“The Years” at Harold Pinter Theatre

Neil Dowden in the West End

15 February 2025

Eline Arbo, who succeeded Ivo van Hove as artistic director of Internationaal Theater Amsterdam in 2023, had considerable success with her production of French writer Annie Ernaux’s Les Années (The Years) in the Netherlands. Then it was revived in an English-language version (by Stephanie Bain) at the Almeida Theatre last year where it sold out after some rave reviews, before now transferring to the Harold Pinter Theatre in the West End.

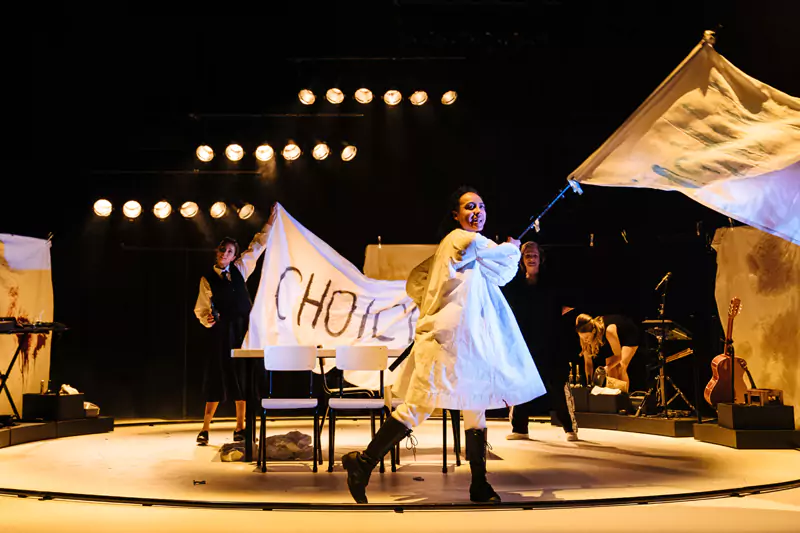

Anjli Mohindra (foreground.)

Photo credit: Helen Murray.

Ernaux won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2022, with Les Années (2008) considered her magnum opus. It has been described as a “hybrid” memoir because it is not only her own autobiography from childhood to old age, but an account of how French society has developed from the Second World War into the new century, especially from a female perspective. The show uses five actresses to play the (unnamed) central woman with each one in turn portraying her at different ages as well as revealing different aspects of her personality. They also alternate in narrating post-war historical developments that give the woman’s individual experiences a wider, social context.

Starting with her early childhood memories of taking cover from bombs in the war and innocent school games, it runs through to her marriage, motherhood, divorce, and becoming a grandmother. Her sexual growth features strongly: comically discovering her sexuality through masturbation; losing her virginity as a teenager to an abusive older man; having a dangerous illegal abortion in the early 1960s; finding more sexual fulfilment in middle-age when having an affair first with a married man and then with a younger lover after her own marriage has ended. Outside her family life, we learn that she works as a teacher and develops into a writer who plans for many years to write the book that becomes Les Années. These seminal life events are enacted with impressive theatricality.

The weakness of the show is that the extended list of world events narrated from the side of the stage simply becomes a chronology that doesn’t always impinge directly on the woman’s life. The changing role and increasing freedom of women in society is clearly relevant, particularly the introduction of the Pill and legalization of abortion. But throwaway lines mentioning the Cold War and the Space Race, wars in Algeria and Vietnam, May ’68, the Palestinian conflict, 9/11, as well as the evolution of consumer society up to the start of the internet age, do not make much of an impact. No doubt this aspect comes across more successfully in the original book, and reflects Ernaux’s own feminist and socialist activism, but it doesn’t work so well on stage.

Photo credit: Helen Murray.

Juul Dekker’s restrained, flexible design features a table and plastic chairs, while multi-purpose white sheets are used to great effect: scrunched up to represent babies, laid out as a tablecloth for family meals, put up on a washing line, or displayed as banners (two of which display the contrasting daubed slogans “Whore” and “Choice” – the former referring to the woman’s public shaming for having sex before marriage, the latter to the campaign for the right to abortion).

The sheets are also used as a backcloth against which actors recreate family photos – which works well when these are older, black-and-white snaps, but doesn’t make so much sense in the colour era. The cast are dressed throughout in the same monochrome clothes so they don’t change garments with changing fashions. A lot of the “visuals” are in fact done by verbal description – revealing the show’s literary origins – so the audience is encouraged to use their imagination.

But this is still very much a theatrical experience with Arbo’s inventive staging, which also includes the cast playing musical instruments – keyboards, guitar, drums – in a minimal way, singing, and dancing at times. The use of music – some of which is recorded – is important in suggesting changing time periods as well as enhancing the spirit of collaboration.

The superb ensemble cast of (in chronological order) Harmony Rose-Bremner, Anjli Mohindra, Romola Garai, Gina McKee, and Deborah Findlay when not embodying the woman herself play subsidiary characters including family, friends, and lovers, with all five remaining on stage for the one hour 50-minute unbroken performance. I say “unbroken” but – as apparently has happened a number of times both at the Almeida and at Harold Pinter – the show had to be paused not just once but twice on the night I attended because two members of the audience fainted during the powerful scene evoking a backstreet abortion. In fact flyers are given to everyone entering the theatre with trigger warnings so people should be aware of this content before the show.

The cast are engaging in their fluid on-stage interactions and supportive sisterhood, especially when they movingly all help to clean the blood from Garai’s legs after her abortion. A more humorous collective scene is when they struggle to keep up with a Jane Fonda-style 1980s aerobic workout accompanied by Taylor Dane’s “Tell It to My Heart”. And they deserve extra credit for having to stand at the side of the stage waiting until they re-start after the enforced breaks without missing a beat.