“The Mirror and the Light”: Gielgud Theatre

Jeremy Malies in the West End

7 October 2021

The Mirror and the Light is the third of Hilary Mantel’s trilogy of novels focused on the sixteenth-century politician Thomas Cromwell. He was a blacksmith’s son who became indispensable to Henry VIII; swayed by his enthusiasm for Reformism in Europe, he persuaded Henry into a disastrous marriage with the sullen and none too hygienic Anne of Cleves. A Royal Shakespeare Company dramatization at the Gielgud Theatre concludes with Cromwell becoming all too dispensable.

The ensemble.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

A virtuoso in her own medium of the novel (for which she has won two Booker Prizes), Mantel could usefully look at the rubric of the often derided “well-made play”. Despite the obviously promising storyline, her narrative simply isn’t compelling enough and, to coin a phrase, isn’t a page-turner.

But this is a different treatment of the text; the first two parts of the trilogy (the award-winning Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies) were dramatized by Mike Poulton for RSC projects back in 2014. As a translator, Poulton is a Chekhov and Ibsen specialist; it’s a background that must have grounded him in the craft of how to propel a plot. In contrast, The Mirror and the Light has been adapted for the stage by Mantel herself working with actor Ben Miles who has played Thomas Cromwell throughout and even narrated all 38 hours of the audio book.

Nathaniel Parker as Henry VIII.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

With the spotlight on Cromwell, Nathaniel Parker – reprising his role as Henry – may well have been given a brief to dampen his own natural presence and charisma as well as the magnetism we associate with the king. Parker is subtle in illustrating how Henry’s obsession with producing a male heir is making him lose his sense of proportion and his grasp on reality, and yet he never predominates. We should be grateful for these different theatrical perspectives on the Tudors; Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons has Sir Thomas More as its focus and in Henry VIII Shakespeare pays great attention to Cardinal Wolsey.

Miles may be a tad too physically attractive as Cromwell. Is this really the pudgy and doctrinally obsessed clerical reformer who peers in profile out of the Holbein portrait? Holbein comes across strongly as director Jeremy Herrin (who has helmed the whole trilogy) contrives to make whole scenes resemble the paintings. He is aided by Jessica Hung Han Yun’s lighting which blends with the use of candles. And indeed, the painter is an on-stage character (played by Liam Smith) with many good gags drawing parallels with how a modern-day despot might employ a paparazzo to snap would-be brides. A vast brutalist concrete set by Christopher Oram (which made me feel as if I was in the communal areas of the National Theatre) contributes to the obvious overall goal of keeping things fluid. There is an avoidance of fussy interiors (even Cromwell’s cell is capacious) perhaps to ensure good sightlines for all parts of the auditorium.

The direction is fleet-footed, and Herrin respects the novel by occasionally hinting that while we are being shown not told, these could also be the thoughts and experiences of Cromwell. I appreciate this respect for the individual theatre-goer and the freedom I had in how to interpret what I saw.

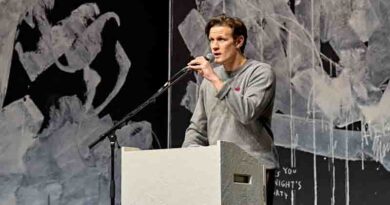

Ben Miles as Thomas Cromwell.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

Handling of the plot also stresses how enormous matters develop at pace. Everything might turn on the fall of a single romantic card, and it’s made clear that had Christina of Denmark come into bat before Anne of Cleves, Cromwell might have remained Henry’s favourite and lived a fulfilled life.

Despite the known tendency for actors in Tudor costume to settle into staid formulaic patterns on the stage, Herrin’s invention injects much realistic movement. There are smooth transitions from intense intimate scenes (we begin in flash forward near the end with the imprisoned Cromwell contemplating his execution) to broad sweeps when characters are presented at court.

The humour is deft as well. As Jane Seymour, Olivia Marcus draws the audience into a wonderful sustained double entendre as she describes Henry’s “unreasonable demands”. He has insisted that she inspects his “fortifications” only for us to finally realize that, with his respect for architecture, Henry really does want her to admire how a newly constructed harbour at Dover has been protected.

So what’s not to like? Perhaps it’s bravura to show Cromwell imprisoned and nearing execution at the beginning and so rule out any cliff-hangers. Of course it makes for a gripping start with our man being visited by the ghost of his dead father. But the overall impression is a curious inertness as though the behemoth that is the plotline is lurching about like a massive fish that anglers (Mantel and Miles) are struggling to capture.