“The Flowers of Srebrenica”, Jacksons Lane

Jeremy Malies in North London

19 October 2025

★★☆☆☆

“What can the world learn from Srebrenica, thirty years on?” ask LegalAliens Theatre. The company is a London-based group led by migrants and known for working with refugee artists. Here they adapt an illustrated novel by Aidan Hehir, an academic at the University of Westminster.

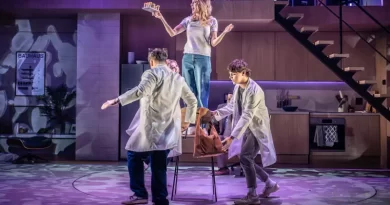

Valeriia Poholsha, Taz Munyaneza, Selma Alispahić.

Photo credit: Raisa Sehu.

This disappointing often shapeless project drawing on far too many disciplines opened in Sarajevo in July. It shows an Irish genocide scholar named Aidan (presumably based on Hehir and played by Jeremiah O’Connor) bolstering his writing output with a field trip to the Srebrenica Memorial Center. Director Lara Parmiani begins with Bosnian actor Selma Alispahić pulling a pair of cheap rubber sandals out of the soil. In doing so, Alispahić conjures up a ghost, Mustafa. He is a Bosniak veteran of the 1992–95 Bosnian War and is played by Edin Suljić.

It’s a strong start and a trio of women suggests a Greek chorus. But I was soon stifling groans as the script (Parmiani is jointly credited for dramaturgy with Becka McFadden) has Aidan trotting out shaggy dog stories involving American tourists and leprechauns on the west coast of Ireland. Sure, there is commonality with diminutive fairies in Slavic myth, but I felt this was token folklore by numbers. Aidan’s discussion of The Troubles in his native Belfast is broad-brush even for writing that tends towards the non-naturalistic.

Add to this a sequence of dire physical theatre (even slapstick) in which other actors pretend to be the car in which Aidan is being driven from Sarajevo to Srebrenica and I began to feel that a sombre subject was being trivialized or at best handled clumsily. Physical theatre and personal testimony (of which there is much later on) do not gel. Throw in animated line drawings, running water effects, silhouetted lighting as well as audio clips, and the result is a mess. The drawings are first-rate and had they been used throughout at the expense of other media the project would have benefited from a coherent backdrop.

Photo credit: Raisa Sehu.

Projection by Edalia Day has thousands of names from genocides across world history merging on tablets and gravestones. There are of course many relevant parallels with genocides resulting from conflicts over religion, most notably in present-day Gaza. And yet less would have been more. I question the inclusion of the Rwandan genocide (at least presented simplistically as it is here) since it involved ethnicity and colonial history. With a Rwandan actor (Taz Munyaneza) in the cast, it is surprising that Parmiani should simply mainline Rwanda into the plot with no context. Later, Sudan, Myanmar, Syria, Kurdistan, and Yemen get thrown into the mix. The piece takes on too wide a canvas and is simplistic in the way that it aggregates genocides or indeed civil wars.

Alispahić comes into the audience twice to hand us soil fragments from Srebrenica. I found this reductive. The play is far more powerful when it deals with particulars such as diary details about trying to pack your life into a tiny rucksack. This chimed with my experience of looking at artefacts in a genocide museum in Sarajevo two weeks ago.

Micro rather than macro might have better underlined the lived experience of the cast in conflict zones. Srebrenica as a killing field comes to life in precise details. I was struck by the number of suicides, a girl called Fatima who lives for just nine months, and a Bosnian Serb Army soldier tasked with the slaughter saying that the executioners had to work on a shift basis through sheer exhaustion never mind any emotional toll. Video and stills of the UN peacekeeping force are combined skilfully and become compelling, but this is individual technical competence within a flawed whole.

A project that could hardly have a bigger remit is ultimately clunky and lacking in focus. I travelled back into central London with a real-life genocide scholar from the Punjab. It seemed best to stick to pleasantries.