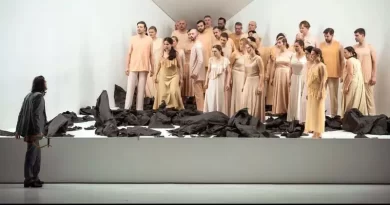

“The Cherry Orchard” at Donmar Warehouse

Jeremy Malies in the West End

8 May 2024

My last exposure to The Cherry Orchard, in Hackney, took me to outer space and had manservant Firs as a robot. The production before (Theatre Royal Windsor) saw 82-year-old Ian McKellen as Firs for a surprisingly bland iteration. In this updating we are right in the present day with Ranevskaya’s lover besieging her with text messages, youngsters peering at tablet devices and what I took to be climate activists, travellers and critics of the gig economy squatting in the estate’s outhouses.

Nathan Armarkwei-Laryea and Posy Sterling.

Photo credit: Johan Persson.

If the plot is to make sense, there must be hints at recent social upheaval and a revolution that Chekhov didn’t live to witness but seems to have foreseen. And that can only happen if the cast are a convincing unit against a recognizable economic environment. This is one of the many merits of a new version of the text by Benedict Andrews which he directs himself.

We are shown a backdrop of drug-taking with these present-day aristocrats (there are flashes of Brian Friel’s play Aristocrats, also at the Donmar) all on uppers or downers. An early piece of action has Ranevskaya’s neighbouring landowner Simeonov-Pishchik (David Ganly) steal her morning cocktail of prescription meds. As the tablets kick in, he charges around the set designed by regular Andrews collaborator Magda Willi. It features a carpet with red ellipses and complex geometrical patterns which extends up the back wall.

“Today, tourism is the fastest growing industry,” says Lopakhin (Adeel Akhtar) to Ranevskaya (Nina Hoss). One of the reasons that the plot of The Cherry Orchard is so malleable is that the theme of brash second-home owners behaving badly in their new dachas speaks to us now. “Drinking sav blanc and working on their tans,” says Lopakhin of the newcomers who he predicts will take up every single purchase opportunity and timeshare.

It’s a large cast and I’ll focus predominantly on Akhtar and Hoss who serve up some of the best naturalistic acting I’ve seen this year or could hope to see anywhere. Placing them close together and with Lopakhin holding a candle, Andrews has the pair almost whisper their recollections of an incident from decades earlier. Beaten by his father, Lopakhin had tottered into the main house bleeding and Ranevskaya had tended his wound. “Don’t cry little peasant, it’ll heal in time for your wedding!”

Adeel Akhtar as Lopakhin.

Photo credit: Johan Persson.

This is a justly celebrated moment in any translation and proves exquisite. As so often in Chekhov, love goes unrequited, but the age gap is not huge and (as played here by Akhtar) Lopakhin’s feelings are ambitious though not ridiculous. But class and money intervene: “Your brother here reckons I’m a thug. A money-grabbing kulak.” As director, Andrews’ many achievements include having the presence of the drowned Grisha permeate space and action as well as split-second marshalling of the exchange between Lopakhin and Varya (Marli Siu) during which comings and goings around them stop the property developer from proposing to Ranevskaya’s adoptive daughter.

Andrews’ translation excels (and makes perfect sense in terms of setting) as eternal student Trofimov (played by Daniel Monks) launches into a denunciation of the true suffering of immigrant workers and mockery of the lesser or imagined grievances of middle-class social justice warriors who are often narcissistic. Andrews is confronting us with the fact that we are tolerating a modern-day serfdom whereby immigrants living in dormitories do the work we would not stoop to. Intellectuals of many stripes are called out in the speech for inactivity and being seduced by social media which is not educating us but contributing to a collective ignorance.

June Watson as Firs is another standout, and her foul-mouthed tirades are not gratuitous but underline that she has advanced dementia. I enjoyed her endless wittering about the estate, covering everything from thoughts about previous generations to what used to be done with the cherry crop. She sometimes carries a tiny samovar as a gag and extracts much comedy with her insistence that she was happier as a bonded peasant under serfdom. All the characters are protective of her and when the klezmer band are onstage, she perches on a keyboard stool shared with a musician as he plays the pinging jazz chords of composer May Kershaw. Elsewhere her music underneath the dialogue focuses on breathy reed sounds.

There are some excesses. If I hadn’t liked the genre, the lengthy mini jazz concert might have been far too long. Interludes where characters pretend that audience members are items of furniture are juvenile and bringing spectators on stage to dance with the cast added little. But it is clear that the characters are aware of the audience; this distinguishes the project from Jamie Lloyd’s recent The Seagull which was visually similar but styled as a rehearsal.

A powerful element is Dan Balfour’s sound design and notably a few minutes suggesting foreboding as we hear a fissure in the hills beyond the estate. (“Like a string snapping in the ether” reads the stage direction.) Switched-on realist Lopakhin speculates that it could easily be a mining disaster involving snapped cables. A boy treble (possibly cast as a member of the travelling community) glides onstage and projects his ghostly voice up to the circle as he sings “Angel from Montgomery” by John Prine. However pleasing, his voice has undertones that suggest social change is afoot and there will be casualties.

I still think that Uncle Vanya and The Seagull are stronger plays if only because high and low points for the characters are set against the relentless ordinariness of their existence. But this Cherry Orchard is a fantastic achievement by Andrews as adaptor and director. His updating makes the story both coherent and challenging while preserving the dynamics of the relationships as Chekhov intended. Outstanding.