“Tartuffe”, New York Theatre Workshop

Glenda Frank in Manhattan

★★★☆☆

26 January 2026

Revivals can be the lifeblood of theatre. Directors get to vie for the most memorable version of a classic, actors are excited to give their interpretation of dream roles, and adaptors can use a masterpiece as their base. Audiences are able to revisit familiar ground either with a new perspective or as a favourite, familiar landscape. But there are landmines aplenty and past productions can cast long shadows.

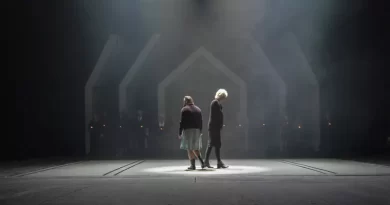

Lisa Kron and Emily Davis.

Photo credit: Marc J. Franklin.

New York Theatre Workshop accepted a challenge when they scheduled Tartuffe which was written in 1664. It is Moliere’s most famous farce and here it is given in a new and salty version by Lucas Hnath (A Doll’s House, Part 2), directed by Sarah Benson (Pulitzer Prize for Fairview and Artistic Director of Soho Rep). But despite some fine performances, the directorial vision is obscure and unaffecting.

Molière (1622-1673) was the son and implicit successor of the official upholsterer at the royal court of the Sun King. But he fell in love with the stage – at a time when actors, prostitutes and heretics could not be buried on consecrated ground. In 1643, when he left Paris with the Illustre Théâtre (a troupe that included Madeleine Béjart who may have been his lover) Jean Baptiste Poquelin had renamed himself Molière to save his family embarrassment.

For almost 15 years he toured the French provinces before returning to Paris. It was a productive apprenticeship. Moliere, who began his career as a clown, had developed into a manager and playwright. Louis XIV’s brother (Philippe I, Duke of Orléans) became the troupe’s patron, and the king offered Molière full support during the several scandals that threatened the playwright’s career. It took royal intervention to ensure that the dramatist could indeed be buried on church ground.

Success had only tempered rebelliousness. Tartuffe or The Imposter is a satire on religious hypocrisy and devotion that riled the all-powerful Catholic church in France. It was banned for five years. Moliere’s other satires, especially School for Wives about a rich man who grooms and rears a little girl to become his obedient wife, had made him many enemies at court but the king appreciated his attacks on the minor nobility.

If a production of Tartuffe is to be faithful to the spirit of the comedy it needs bite, a feeling of outlandish situations and characters teetering on the edge of a cliff. Adapting any play that is almost 400 years old is a challenge. Hnath’s rhyming couplets are often clever, but he and director Benson chose stylization and pungent language over dramaturgy. Other decisions were equally curious. When Dorine (Lisa Kron), the plain-spoken maid, began to use emphatic profanity, I was impressed since this seemed in the spirit of Molière and a way to define this particular servant. But when the other, more sophisticated characters also adopted four letter words, the foul language lost its effectiveness.

Amber Gray and Ryan J. Haddad.

Photo credit: Marc J. Franklin.

Tartuffe tells the story of a late-life infatuation, only the love object isn’t a woman or a sports car or a racehorse but a religious hypocrite who offers to lead Orgon, head of a prominent family, along the path of redemption. Orgon refuses to hear any of the many hints that Tartuffe is a swindler. To prove his affection, he signs the deed of his property over to this new guru.

Orgon’s mother, Madame Pernelle, a minor character, is a fast-talking religious bully who dominates her son and his family – much to our amusement but to everyone’s else’s distress. They can’t get a word in edgeways. Casting a trans actor (Bianca Del Rio) in this role with over-the-top make up unsettles the balance of the play, taking us out of Moliere’s delicately balanced comedy and into the world of drag performances. (Del Rio won the sixth season of “RuPaul’s Drag Race”.) Based on the mismatched acting styles throughout, it seems that comic turns were foremost in the director’s mind. Rarely are the plights of Marianne, who seems destined for a May-December match with Tartuffe, and Damis, who is disinherited, allowed to be emotional affecting.

The two stand-out performances are Matthew Broderick (Plaza Suite) and Emily Davis (Obie and Lucille Lortel awards for Is This a Room). Broderick has a stillness that upstages everyone each time he enters a scene. His Tartuffe is more a genial uncle than a conniving con man. He watches with bemusement as Organ (David Cross) ties himself in inextricable knots to please him. He is never less than honest, confessing to all sorts of corruptions, but just when it seems the mountebank will be exposed, Orgon make excuses for him. Only when Orgon comes to his senses does Broderick’s Tartuffe reveals his tempered steel spine.

Davis’s ingenue is also played against type. Davis is a clever clown whose stylized, exaggerated gestures reinforce her words while undermining them. It’s a tricky balance. Like Broderick’s, her performance is memorable and her choices surprising: she makes you want to see more of her.

Benson uses some standard comic devices in her direction to good effect. After Damis (Ryan J. Haddad) is banished from his home, he exits and re-enters repeatedly like a jack in the box. Ikechukwu Ufomadu plays several roles and at the end he embodies these in such quick succession that the transitions are a delight.