“States of Innocence”, Brighton Dome Corn Exchange

Simon Jenner in Brighton

May 19th 2024

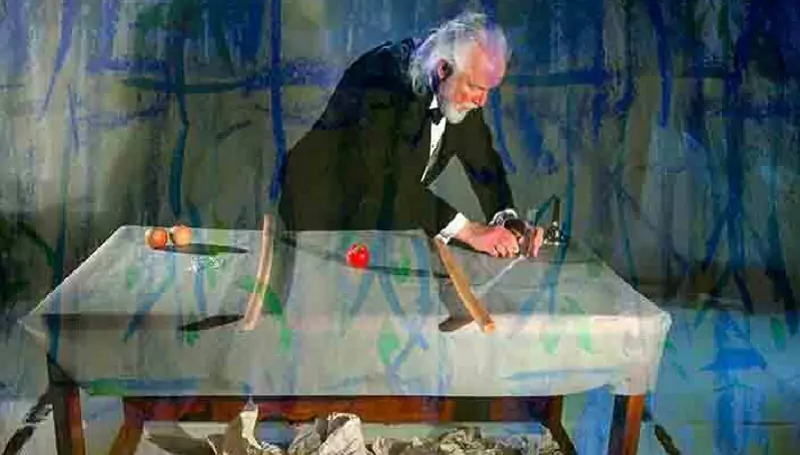

Ed Hughes’s mesmerizing States of Innocence, conducted by Andrew Gourlay with stage direction by Tim Hopkins, was given a single performance at Dome Corn Exchange as part of the Brighton Festival.

It’s a semi-staged opera lasting 85 minutes with libretto by Peter Cant, exploring doubleness: characters flit in and out of Milton’s Paradise Lost and back into scenes of the poet organizing his household to help him write his masterpiece. It’s depicted as a “dreamlike unfolding” of Milton sleeping on his vision, counterpointed with daytime writing and dictating.

The opera is resolutely tonal, though if that suggests Jonathan Dove’s Flight, it is spikier, with an onstage instrumental septet both dissonant and harmonically daring. Tonal, but not minimalist, it’s an approachable but beguilingly contemporary idiom. Flute and clarinet lead through strings and piano a punchy, never vehement score.

Like the poem, 12 scenes traverse the arc of G major – the music’s home key, traditionally depicting optimism and cheerful energy. There is textural variety, though like the poem itself, not in terms of pace. Unlike the poem, it doesn’t highlight the eleventh scene’s Fall as musically catastrophic. And though there is correlation between these scenes and Milton’s books, that is not (happily) adhered to rigidly. Yet it holds attention.

Partly this is visual. There is a hard-working complement to the necessarily static nature of performance. Twelve sections are signalled on Ian Winters’s projection design filling the backdrop. It shimmers with period jottings and manuscripts, scientific images and what seems a psychedelic ride through a seventeenth-century library. This features enlarged images of performers while sliding each projection to fresh imagery.

For instance the purely instrumental section VIII “Interlude” (giving singers a well-earned break) allows us to imagine Milton in his younger days contemplating Keplerian harmonies of planets, original drawings turned into a graphic dance of the spheres.

Lighting from Beth O’Leary and Jazmin Field draws performers into this field. There is a complementary colour-blocking with various shades emanating from the stage itself.

Melodically there is a spiral ascent. Each section is introduced with, for instance, “Supplication” to begin and finally “Banishment”.

Five soloists are used unevenly, four named. In nearly every scene Milton (Sir John Tomlinson) is to the fore. His bass-baritone cuts through magnificently as narrator and almost as a continuo voice, leading vocally through the different timbres.

Eve (Rozanna Madylus) in an eloquent deep-toned soprano. She soars into self-knowledge over sustained coloratura lines: not just as Eve but Wife too. She enjoys the next most extended role in her doubled world as Eve.

In the third part “Eve’s Awakening” she is joined by high soprano Rachel Duckett (piercing and sharp-edged to Madylus’s richness) as her reflection. That is when Eve notices in a pool how beautiful she is.

Madylus’s role as Wife is not as sharply defined, and one wonders what kind of opera Hughes and Cant might have addressed if they had made more use of the chorus (Zofia Reeves, Liz Webb, Natasha Stone) here standing in as Milton’s three put-upon daughters. They allegedly stole his books for money, being kept so meanly; and to an extent rebelled, even sabotaged Milton’s work.

In the faster tempo of the second section “The Household” there is a tantalisingly brief agency for Reeves, Webb and Stone as daughters aroused to work as amanuenses: yet one longs for definition, dramatic bickering.

As it is, Secretary (often scurrilous nephew John Philips who brought those charges against Milton’s daughters) gets the discontent, though not explicit motive. His chief role is Satan where lyric tenor Thomas Elwin, standing in for Stuart Jackson, becomes prominent.

In the fifth section (“Satan’s Entrance into Paradise”) and seventh (“Perdition”) we enjoy slithering lyricism – and surprisingly light textures. Elwin revels in high sliding scales and what Hughes and Cant also posit as Milton’s queerness depicting Satan. It’s a compelling musical logic, allowing Satan not only the best harmonies but someone writhing into light.

The poet Andrew Marvell also acted as amanuensis, saving Milton from prison and execution. Now that’s an opera on its own.

Adam (Matthew Farrell standing in at very short notice for Tim Morgan), has less to do, but as a lower tenor he is able to echo Tomlinson and occasionally as in IV “Adam’s Account” to carve some individual power. Only Tomlinson’s ebony-carved voice cuts through with ideal clarity. That is no reflection on singers: bass timbres usually do this.

Farrell has more to do in erotically-charged book X “The Hour of Noon” featuring ravishing sting textures and wide-ranging harmonies from flute to piano. That is true of XI “Original Sin” with further exchanges between Farrell and Madylus, with Tomlinson edging in. It would have been good to see interplay between Farrell and Duckett.

VI “The Hour of Night” invoking Britten and Bartok’s night music is dark-hued, musically satisfying. Eden’s green is struck through with nightmarish yet sylvan possibilities. Indeed dense arboreal stretches are part of the overall visuals – in almost every section we’re treated to green thoughts and green shades (Marvell certainly comes to mind here).

The relation between composer and librettist is more equal than a blind poet imposing words on multiple helpmates including a secretary. Nevertheless, there is some witty interplay between Cant and Hughes; the scurrilous secretary doubling as discontented Satan, powers behind thrones.

With Mrs Milton turning into Eve without much motive, one might ask which Mrs Milton Milton had in mind? All three might have informed Milton’s imagination and one wonders what his unhappy rebellious first wife Mary might have contributed. Katherine Woodstock “my late espoused saint” died just after childbirth, yet Milton was happy with much younger Elizabeth Mynshull. (She angered her step-daughters.) Cant and Hughes have opted to streamline everything to the poem, doubling to its function.

Musically this score is seductive and 85 minutes proves hypnotically ideal. The New Music Players are superb. Karen Jones’ flute and Fiona Cross’s clarinet lead writhing upper textures, perky interjections and spiky dissonances.

They are abetted by gorgeous low-note slithering by Alison Hughes’ bass clarinet. Just three string players – the acclaimed and much-recorded Susanne Stanzeleit on violin revels in suspended ecstatic moments, as does Bridget Carey with her viola’s added richness. Andrew Fuller, another recorded chamber soloist, adds a cello counterpoint to the bass clarinet.

Finally Ben-San Lau’s piano is everywhere, both in the score’s percussive reach and its glinting top-notes: here the piano is the great leveller.

Following Milton’s storytelling but not its dramatic moments, States of Innocence refuses to force a different dynamic. Overall Milton’s tenor is even; so, as a dream, is this.

Though Haydn’s The Creation used Paradise Lost as a launchpad for his most innovative orchestral introduction of chaos, he dodged the Fall. Hughes has absorbed it, painlessly, as a creative state of mind.