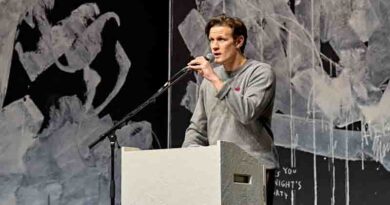

“Semele”, Glyndebourne

Simon Jenner in East Sussex

25 August 2023

If you were thinking The Playgirl of the Western World as the scene goes up on a boggy (later scrubland) set depicting Thebes in Handel’s 1744 Semele at Glyndebourne, director Adele Thomas might agree.

Joélle Harvey and Stuart Jackson.

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

The cast are mostly in pale green and there is an Edwardian feel, circa 1910? They are crowded round bog land that resembles John Synge’s Arran Islands. This is a dour, acidic world. Designer Annemarie Woods’s unrelenting flatlands are often illuminated only by marsh-light in Peter Mumford’s lighting with few exceptions. One of the exceptions is a rainbow, depicting Iris, goddess of rainbows whose hues contrast the restricted palette elsewhere.

It seems a patriarchal community from which Semele as interpreted by Thomas wishes to escape. Costumer designer Hannah Clark ensures it’s also inescapably early twentieth century. The gods are another thing.

Alone dressed in white, already pregnant, doubtless dismissed as a playgirl, Thomas gives humanity as well as agency to Semele (Joélle Harvey) and later to her younger “playmate of my tender years” sister Ino (Stephanie Wake-Edwards).

Thomas says she takes inspiration from industrial south Wales. Some might think of Gary Owen’s Iphigenia in Splott. There, a pregnant woman is desperate to escape too. Splott in Cardiff could be the wasteland depicted here: grey-green pools of acid waste or Irish bog. With Clark insisting on period, it fits better.

It’s also late Restoration comedy; perhaps (with Thomas Otway) the best Restoration tragedy too. Written by Congreve in 1706 for the prodigiously gifted Master of the King’s Musick John Eccles after Congreve retired at 30, (he returned only for libretti), it was never produced. Handel knew Eccles. Judging by the 2003 recording of Eccles’s work, he took more than the libretto.

Jennifer Johnston, Clive Bayley and Samuel Mariño.

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

This is understandably called – with Hercules – Handel’s greatest opera. Handel clears out most brass and woodwind. Strings do huge, heavenly lifting; there are just three core instruments. Conductor Václav Luks’s harpsichord, an active theorbo (resembling a stretched mandolin), and chamber organ. This is unnervingly close to Eccles’s more modest 1706-style forces. Luks’s conducting of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment is flamboyant too.

It sounds like nothing else in Handel. Even with the wonderful Glyndebourne chorus, directed by Aidan Oliver, this is intimate, intricate writing. Every colour registers and few opera houses can deliver rapt sonics like this one.

Unlike Eccles (where the intact libretto can be read), Handel removed explicit sexual references, literally incendiary orgasms. He then snuck in other Congreve lines. That most famous aria “Where’er you walk” is Pope’s. And though he cuts words, Handel replaces eroticism in music, particularly “pantings” and “faintings” stroked lovingly with violins and double-bass.

Handel’s penultimate opera Semele, with Hercules the next year, enjoys position that is an anomaly: opera in English with religious, oratorio choruses, and like oratorios, not staged. With secular texts neither were called oratorios but Charles Jennens (librettist of Messiah and other Handel oratorios) called Semele “a bawdy opera”. And there are biblical choruses. Welcoming an illegitimate brat already drunk? That is to anticipate.

After the riveting, nine-minute sigh of an overture, Semele, pregnant by Stuart Jackson’s Jove, is yanked towards the arranged marriage her father Cadmus (Clive Bayley, an inky bass of real power) is pressing her into with Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen’s Athamas. He is keen though it’s Wake-Edwards’s Ino, not Semele, who is keen on him.

When Wake-Edwards unleashes her mezzo, it’s heart-rending, confiding, then wrenched into desolation. She is also perhaps the clearest vocally in an evening where there is great clarity elsewhere.

Cohen’s Athamas will need to match Wake-Edwards’s empathy for his condition, and he does. His creamy high tenor is rapt, sympathetic but wrong-hearted, where Athamas suddenly realises too late quite why Ino is so comforting. It’s a marvellous duet, the most emotionally compelling of Act One.

Thomas fleshes out Ino’s character in particular, ensuring she’s not to be picked up so casually either, when subsequent events bring Athamas to her. This also involves her great attachment to Semele, whom she does not blame.

Having suggested Semele needs to escape a toxic land and people, Thomas and Harvey make her exuberant sexuality a natural one, if occasionally a bit triumphant. Her ambition too, despite Congreve and Handel, is logical.

With a few crashes that caused visible alarm in the stalls, what looks like a fantastically encrusted ordnance survey balloon-basket descends after the abduction. Semele, with a spent, dozing Jove, now gives “Endless pleasure, endless love / Semele enjoys above”. This aria was originally given to a priest. In a masterstroke, Handel makes Semele sing regally of herself in the third person.

Harvey though is now in lyric flight, having started in a muted tone earlier. Her voice from here on is full and rich as well as effortless, secure, bouncing all the dotted rhythms with as much abandon as The Queen of the Night.

“Useless now his thunder lies” gets a ripple of laughter since Jackson is slumped. Surprisingly, the first interval does not come there, but into Act Two.

Juno (Jennifer Johnston) and Iris (male soprano Samuel Mariño) arrive wearing jealous green. Their powerhouse costumes cross Turandot with The Wicked Witch of the West. Mariño’s voice, pure and piercingly high, is one of the most beautiful of the evening. Bayley is also knocked up as the comical god of sleep Somnus, woken with a sexual bribe to plague Semele. He breaks convention by dozing off, never finishing his da capo aria.

Johnston’s ringing mezzo fury is like an acetylene torch at moments. It burns down everything it touches vocally. Who needs thunderbolts? Juno’s jealousy at Jove having overstepped the bounds of infidelity can hardly come as revelation. By impregnating Semele with a three-quarters god (Semele’s mother was Harmony, so surely she’s a demi-god) perhaps Jove’s ensured the god-quota has been disturbed. In any case Juno’s nature is fidelity, the wound a livid scar.

Assuming rightly that Semele wants immortality, Juno lays the trap. Ask Jove to promise to reveal his full godhead. Originally this meant fiery semen. So the moment is now muted. But the request gives us pause on a type of class politics. The number of mortals made immortals by gods is vast. Yet Jove declares: “I must not understand her.” Unless he has been given a strict conversion-quota the artificial tension is one of those imponderables.

Jove’s first recourse is to distract, by uniting the sisters in Ino’s visit. It’s the tenderest moment where again Wake-Edwards’s capacity to blend mesmerizingly with soprano as well as tenor makes both singers dazzle; especially with both listening to the music of the spheres. She’s even finer alone.

Act Two furnishes Jackson’s transfixing “Where’er you walk”; and Jackson is now active through the rest of the opera, in acid fluorescent yellow (as if a mutant from the aforementioned soil) padded out to seem massive.

His ringing low tenor lines and baritonal reach create an instrument of flexibility with power in reserve. Yet Jackson can purr down to the lowest reaches. His two big arias rightly stop the show, while his plaintive “My lovely fair” with its descending figure much later, after Juno has got at Semele, is even finer. Jackson makes of Jove a god incapable of his own powers; but detached too, if hyper-aware of his force.

It’s Harvey, with her trumpet-tongued “Myself I shall adore” who nails Semele’s complex personality. When deceptively handed a distorting mirror by Juno-as-Ino, her looks enhanced, she steals the show in her selfie-moment. The second line “if I persist in gazing” shows a more ironically self-aware woman. Though exulting Harvey shades a knowingness to this.

As Semele’s ashes die in an overt Wicker-Man frame, which returns to a Juno shrine, we’re reminded that here is nothing but superstition. A blazing chorus is subverted from its oratorio religiosity as Thomas depicts a Bacchic writhing. The black-clad choir sprawl and kick in the air as little Bacchus (Ailsa Bond Vannuffel in this performance) pops up from the ground; from Semele’s charred womb.

It’s the best moment of Emma Woods’s choreography. Tethered by characters trying to exit but necessarily yanked back to hear an aria, baroque blocking can prove thankless. Here finally, Woods give us apotheosis.

But Thomas isn’t done. Wake-Edwards’s Ino, now forcibly united with Cohen’s Athamas, is still grieving. She writhes against his forced kiss. Had it been earlier, it would have been welcome. She may warm to Athamas, but the message is clear. Semele was right. Get out of this toxic place.

.