“Romeo and Juliet”: Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre

Julie Sorokurs in central London.

25 June 2021

Director Kimberley Sykes’ production of Romeo and Juliet premiered at the central London landmark of the Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre this June [2021], and even with the likes of Baz Luhrmann’s dizzying and pell-mell movie Romeo +Juliet (1996) to compete with, this iteration took on a refreshing and memorable urgency, its titular characters flying through their soliloquies and into one another’s arms as only lovestruck adolescents would.

Isabel Adomakoh Young and Joel MacCormack.

Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

The driving concept behind this production is best introduced with Sykes‘ own note in the programme, on the speed at which the events of the play take place. “Four days, six deaths, one Verona.” Taken out of context, these six words look best placed at the bottom of a film poster for a crime thriller starring Keanu Reeves. It appears that one of Shakespeare’s best-known love stories still has the capacity to thrill and excite.

Sykes’ production has been streamlined and stripped down to highlight just how quickly the two go from their first encounter to their secret wedding ceremony and then, inexorably, to their deaths. The brevity of its runtime notwithstanding, this Romeo and Juliet nevertheless brims with such feeling and dynamism that I was taken aback by how moved I was during its final moments.

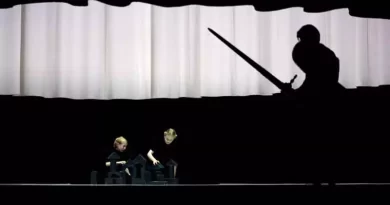

The pace is set with the introduction of Romeo and his lively posse, all dressed in black (in contrast with the Capulets’ entirely white garb), the swaggering and restless Mercutio very much at the forefront. Kicking up the dust of Naomi Dawson’s spare and scaffolded stage, Romeo and company weave between high metal beams with some members of his party scaling the scaffolds to spy on, jeer at, and hide from those down below.

Cavan Clarke’s Northern Irish Mercutio is the perfect foil to Joel MacCormack’s more thoughtful and angst-ridden Romeo. All eloquent derision and bawdy provocation — Clarke’s full-body delivery of “If love be rough with you, be rough with love” being an especially memorable moment — this production’s Mercutio also serves as a reminder of the degree to which the tone of the play shifts after his death. Clarke is so much a highlight that, with Mercutio’s exit, his absence is sorely felt on the stage. (Mercutio is, after all, “the most notorious scene stealer in all of Shakespeare” according to Harold Bloom.)

The ensemble. Stage design by Naomi Dawson.

Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

The same must be said of Michelle Fox’s Tybalt, uncompromising and hot-headed as she is, and indeed of Isabel Adomakoh Young’s impatient but determined Juliet (a perfect contrast against MacCormack’s more depressive Romeo). The chemistry between Young and MacCormack is electric, their desperation to be together so evident and so great that I started wondering whether their scheme with Friar Lawrence might actually work. As with Shakespeare’s other more “mainstream” plays (e.g. Macbeth, Hamlet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream), it’s important to not take spirited performances like these for granted.

It speaks to the strength of Fox’s and Clarke’s performances especially that when this production has both characters “leave” their bodies at the moment of death, and join the audience in watching the goings-on on stage, what would normally be too melodramatic a device for my liking still works. Melodrama is integral to this production — from Juliet’s breathless soliloquies, to the swelling orchestra of strings (Giles Thomas) that accompanies the lighting of numerous torches as the play concludes — and it works because it aligns so convincingly with the inner turmoil of every one of our main characters, truly swept up as they are in love and in hate.

There were still some choices made by the creative team that laid on the melodrama a little too thickly. Two sandbag-timers, awkwardly placed in the middle of the stage, seemed to be waiting, just a little too obviously, to be eventually split open and have their contents cascade down onto the stage. “Time ls running out! Get it?” Even more gratuitous were two glass cases mounted to the scaffolding, also waiting to be broken, a rapier contained within each one (Mercutio and Tybalt do clumsily break into these and, honestly, I’m not sure that some of the resulting bloodstains were planned).

At odds with these more obvious theatrics was the most memorable part of this production for me — a great big crack down the stage (that I initially mistook as a permanent characteristic of the open air theatre’s venue). This served as a reminder of not only the earthquake that shook Verona eleven years previously (Nurse recalls it in Act 1, Scene 3), but also of a lasting rift between the Montagues and Capulets. Sykes’ decision to literally centre the production around this fissure made for a remarkable visual metaphor, and ominous harbinger, of what was to come; like with an earthquake (sudden, violent, brief), tragedy overwhelms the Montagues and Capulets before either side has an idea of the magnitude of what has happened.

Joel MacCormack and Isabel Adomakoh Young.

Photo credit: Jane Hobson.