“Polishing Shakespeare”, Edinburgh Festival Fringe

Venue: Assembly Rooms (Front Room)

To 25 August

Venue 20

Duration: 60 minutes

Two-star review ★★

A billionaire, artistic director of a theatre and a playwright walk into a room. The billionaire, Grant, is funding the theatre to produce his idea which is a translation of Shakespeare’s plays into English.

The first thing to strike you is something strange about the language they use. There is an abundance of wordplay, and one quickly realizes that they are speaking in (rather clunky) iambic pentameter. Brian Dykstra (who stars in his own play as the wealthy thespian philanthropist) and his co-writer Margarett Perry clearly have a deep love and appreciation of Shakespeare’s language, missing no opportunity for alliteration, rhyme or double entendre. The idea of writing it to sound like Shakespearean dialogue is fun. But this quirky imitation is only superficial, and quickly becomes tedious. It persists regardless of the character or their circumstances. That said, there are many in the audience who appear to be delighted by the language and humour.

The jokes are declaimed (incredibly loudly) by each of the powerfully-voiced actors, who could fill a stadium with their presence, somewhat compromising the intimate size of the venue. There are a number of genuinely funny gags, the best of which made me laugh. Disappointingly, the best gag is followed up by a line that explains it, in case it’s not explicit enough.

It’s a shame, because I find the premise genuinely original and compelling. Grant specifies that he wants the playwright to produce “a translation … not an adaptation” of Shakespeare’s plays into more accessible English. There is an interesting case to be argued there.

For one, most popular stagings already “translate” lines for clarity without sacrificing meaning or metre, such as replacing obsolete “an” with “if”, or changing important lines of exposition, which are obscured by classical allusion, to something metrically equivalent: Emma Rice’s Twelfth Night replaced “Elysium” with “a watery grave”. In a production of Othello, Nicholas Hytner did something similar to clarify what Emilia is saying when the Moor’s famous handkerchief is found, and she says she will duplicate the embroidery.

Furthermore, the plays of Shakespeare enjoy a greater degree of perceived relevance among the general populations of countries that read and perform them in translation: they benefit from up-to-date translations in every major language apart from English. There will come a time when Elizabethan is no longer intelligible. Where do we draw that line? There are more questions to be posed about the elitist notion that the audience are at fault for struggling to understand.

Unfortunately, Polishing Shakespeare engages with none of these arguments. Instead, Dykstra and Perry present an altogether one-sided lampoon of the idea. Rather than using the character of Grant to delve into some of the nuances of the translation question, he is purposed as a two-dimensional strawman, explicitly telling us he wants the writer to “dumb it down” in order to attract “stupid” audiences.

This is evidently a missed opportunity and is symptomatic of another problem with the play: the characters are thinly drawn and only superficially distinguished. They all speak the same way and behave in accordance with what is convenient for the writer’s agenda rather than what is plausible. One of the qualities that makes Shakespeare’s dramas so compelling is his ability to present mutually contradictory but convincing viewpoints in conflict with one another. Each character has a unique dynamic perspective, and each is equipped with a persuasive argument for why they are right and everyone else is wrong. This is one of the many elements of Shakespeare’s style that Dykstra and Perry do not adopt.

Even more underwhelming was the structure. There is a clear call to action for the writer to translate a Shakespeare play. She does not do that, and the play ends with her threatening to stage a play that satirizes Grant, and him threatening to retaliate, without a great deal of closure.

After the first scene, she has a moment of reflection where she considers “selling out” and taking on the project. Despite actor Kate Siahaan-Rigg’s valiant efforts, this scene fails to prove emotional because there is no sense of the stakes that the decision presents for her. Then, instead of selling out, she writes a modern-day adaptation (crucially not a translation) of Henry VIII, which sets out to criticize and expose Grant. It is only fitting, she argues, that a work that compromised on its values to appease its funder (King James I) should be the basis for a satire of its own funders. However, the fact that her play is doing the exact opposite of what Henry VIII did (i.e., satirizing, not appeasing) means it is neither a translation nor an adaptation.

And that is pretty much it. For such a long play, there is little action, emotion, meaning and (for me at least) humour. The performers are strong, but the writing fails to deliver on the potential of its premise.

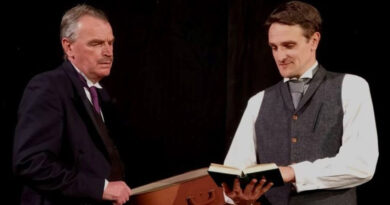

[Photo above, credit: Carol Rosegg.]