“Othello”, Lyric Hammersmith

Jeremy Malies in west London

29 January 2023

Frantic Assembly’s version of Othello, previously staged in 2008 and 2014, has now been updated and after a ten-date tour returns to the Lyric Hammersmith where it was first developed.

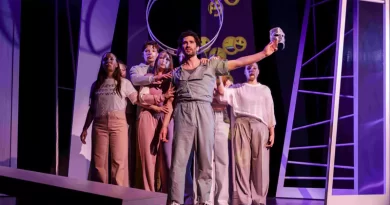

The ensemble.

Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

I’ve missed the previous productions and found it fresh and logical. But a little of the violent pub culture that is the setting here and which company creators Scott Graham and Steven Hoggett cite as the inspiration for much of their work went a long way for me. Does it stretch to anchoring a Shakespeare tragedy even with the company’s deft adaptations? Three things divide Othello and Desdemona as written by Shakespeare: age, social class, and ethnicity. Age and class are gone here – stripped out wholesale. But yes, the narrative still works because it’s robust, the textual cuts are thought through carefully, and Frantic Assembly see every aspect of the original plot in a wider context.

It’s a bad start. As Desdemona, Berkshire-raised Chanel Waddock injects such an extravagant faux Cockney glottal stop into her first line that she gets what is surely an unwanted laugh right through the stalls. Graham (or an uncredited voice coach) has let her down. Rupert Goold of the Almeida once explained to me how Shakespearean verse can co-exist with many idiomatic patterns of speech. But this was assault and battery though thankfully it receded and characters began to sit on the pulse of the metre.

Chanel Waddock and Michael Akinsulire.

Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

We are in The Cypress pub (the action barely leaves it) and the design for a set by Laura Hopkins that has travelled across the country features a huge sofa, fruit machine, and, centre-stage, a pool table which anchors the production. Some of the fighting takes place in a yard full of enormous refuse bins. It’s on the pool table that we see the company’s trademark tightly co-ordinated physical theatre as Desdemona and Michael Akinsulire (Othello) intertwine. It’s fluid and precise choreography from Perry Johnson and they create lovely arabesque patterns. But however beguiling the shapes, I don’t detect an unusual buzz between the pair.

Gone (quite sensibly) are all references to Italy and a reasonably ordered barrack room society is replaced by gang rivalries full of toxic masculinity. As Akinsulire belittles Cassio for never having “set a squadron in the field” he could easily be talking about setting up young drug couriers in county lines. And when Cassio (Tom Gill – excellent) bemoans loss of “Reputation, reputation, reputation!” we see it as loss of drug turf and think of the (grammatically unsound) current concept of “disrespecting”.

It will be obvious that I have reservations about this but to accuse Frantic Assembly of tampering with Shakespeare’s text (as many conservative theatregoers do) is deeply ignorant; they simply remove speeches to adapt the story to the setting they have chosen. What remains is the authentic dialogue, monologues, and soliloquies as you will find them in any mainstream printed edition. There is great respect for text.

The cast is extremely young; even Brabantio who is supposed to be Desdemona’s ageing father is played by the vibrant Matthew Trevannion though all mention of the character’s frailty are removed. A Welsh playwright as well as actor, Trevannion impresses later when doubling up as a truly malevolent Lodovico.

One of the many plus points is the music by Hybrid which ranges from house-pop to hip-hop and even some lush orchestration in the style of an epic film when we are being asked to imagine the world beyond the pub. Fights (again by Johnson) are at two levels: a balletic theatre as part of group movement and a change of tone with realistic simulation of vicious combat between thugs. I found it amazing that all this could be fuelled by five-percent-proof Heineken though I detected occasional cocaine sniffs from Oliver Baines’s Montano.

Chanel Waddock as Desdemona.

Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Akinsulire is at his strongest when he surrenders himself to the flow of the major speeches, notably when describing his early life and telling us that the only witchcraft he has used to enchant Desdemona is describing his travels. And Waddock settles into her role. She proves skilful in another choreographed sequence (yet again on the pool table) when she suggests just the right amount of innocent tactile flirtation with Cassio to leave us in no doubt of her loyalty but still arouse her husband’s unfounded suspicions.

Later, Gill as Cassio and Hannah Sinclair Robinson, a Frantic Assembly regular and Shakespeare specialist playing Bianca, generate greater chemistry and are more credible as a couple than the principal characters. Waddock isn’t helped by being deprived (moments before her death) of the Willow Song which goes completely, the one cut that I see as a mistake and a cop-out. It could have been done in any style including karaoke which would have suited the pub setting and its absence takes poignancy away from the murder scene. I feel no shudder as I expect to do when Othello asks if she has said her prayers.

There is an inescapable equation in this play: the better your Iago the more difficult it is for your Othello. Joe Layton (as Iago) is a little too clean-cut and the least evil-looking person on the stage. But his verse-speaking is first-rate as he negotiates his way through the often obscure sexual puns that litter his speeches.

The best scene of the evening comes as we see Emilia (Kirsty Stuart) and Waddock in the pub toilet which is a clinically white set within a set having been wheeled on. Both actors give their characters a fatalistic calm and Graham’s direction puts the brakes on what has been a pell-mell pace. Stuart identifies gradations of promiscuity as the pair discuss whether it might be excusable to cheat once on your husband in order to offer him untold material wealth as a result. A few years older than most of the cast, Stuart can suggest the life experience that makes her character’s pragmatism believable. And she hints at how, in full-length versions such as one reviewed by a colleague only weeks ago at the National Theatre, her character can become the moral centre of the action. But it’s a rare moment of convincing introspection in a play that should abound in it.

Michael Akinsulire as Othello.

Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.