“Not About Heroes”, Mercury Theatre, Colchester

Jeremy Malies in Essex

26 October 2018

You hardly needed to be a scheduling genius to realize that a prolonged tour of Stephen MacDonald’s 1982 play Not About Heroes with its treatment of First World War poets would be opportune over the last few years. The important thing was that the piece should be in safe hands and the production should befit the magic of the writing and the momentous historical backdrop. Flying Bridge Theatre Company score well on all counts in this portrayal of writers Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen at an Edinburgh nerve clinic in 1917.

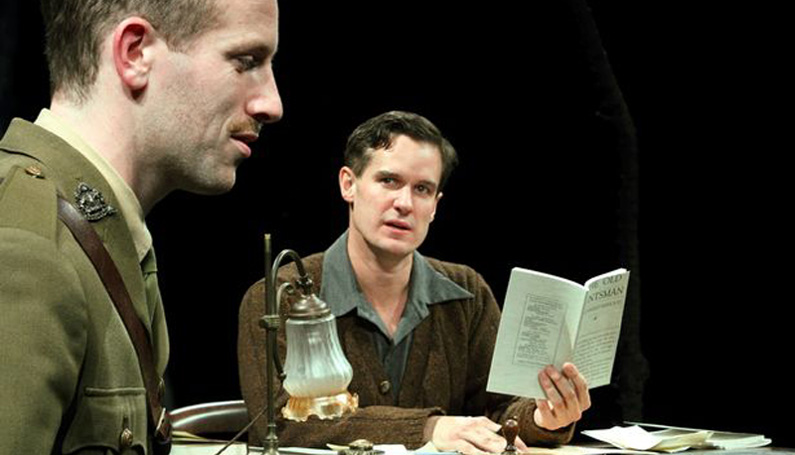

Owain Gwynn as Wilfred Owen.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

The play is book-ended by the later reflections of Sassoon beginning in 1931 but the core of the action is flashbacks to the time the poets spent together at the Craiglockhart War Hospital. Daniel Llewellyn-Williams is particularly effective when illustrating Sassoon’s survivor guilt, his world-weariness, and the contradictions in his behaviour which must have proved testing for his superiors. (He was attracting publicity by writing anti-war tirades but had won the Military Cross while single-handedly taking out an enemy trench and scattering 60 Germans during the First Battle of the Somme a year earlier.)

As Wilfred Owen, Owain Gwynn conveys his character’s sensibility to the mechanics of verse and shades of meaning in language. The script is as much about the craft of writing poetry as it is about war, and an exquisite scene has Sassoon making suggestions about the younger man’s word choices. The realisation that the poem is taking shape as ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ sent a collective gasp around the auditorium. It will stay with me as the defining moment of a play that has much to say about current theatres of war.

Director Tim Baker and his cast respond to successive challenges such as a scene in which one writer’s letter home is interspersed with fragments of the other writer’s verse. When Owen’s frayed psyche starts to reassemble itself, Sassoon reins in his natural brashness and patrician manner in order to nurture his friend. Gwynn is skilful in hinting that Sassoon or a therapist need only make one ill-judged move and he will subside into catatonia.

Owain Gwynn and Daniel Llewellyn-Williams as Wilfred Owen.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Llewellyn-Williams nuanced depiction of Sassoon suggests that blind patriotism is an uneasy bedfellow with an analytical mind. We also see his quick appreciation (and generous spirit) as the younger inexperienced poet begins to excel him in quality of poetry. Meanwhile, Gwynn implies that Owen is the less restrained in terms of showing physical affection.

Oliver Harman’s split set design juxtaposes belts of barbed wire, shell holes and munitions with a desk and bed for the hospital. With only a few bold strokes, he conjures up the horrors that await the characters when they return to France. The incomparably brave Sassoon finally got a ticket to Blighty in a friendly fire incident while Owen was killed by a sniper on the banks of a canal only a week before the end of fighting.

Watching projects over the last four years commemorating the centennial of the First World War across theatre, opera and even ballet, I’ve reflected that if there is another global conflict there will be no anthem for doomed youth; annihilation without documentary record let alone art will be almost immediate.

Even a cursory look at the audience in Colchester (a garrison town from Roman times right to the present day) suggested that the theatre-goers included present and former service personnel across all demographics and ranks. I would wager that there were PTSD victims present. There would certainly have been hidden scars. This was the most moving part of an evening in which rapt attention underlined the restorative power of drama.