Two New Medeas in Connecticut

Robert Schneider

29 March 2023

The difficulty in adapting Medea for modern audiences is clear: we must be horrified by Medea’s slaughtering of her children yet also understand its necessity. We need to take Medea’s side at least in part. For ancient Greek audiences the task was made easier by the way they understood motherhood. The Greek equivalent of DNA resided entirely with the male who only lent it to the female for the nine months of gestation. The mother’s bond with her children was thought to be merely sentimental, not genetic. Medea had to kill the children she had with Jason in order to cut off his line and save the world from endless replications of Jason’s deceitful, male DNA that gurgled undiluted in the bodies of his children. It was an act of vengeance, but also of social hygiene.

Alma Martinez (foreground) in Mojada: A Medea in Los Angeles.

Photo credit: Joan Marcus.

In a single weekend I’ve seen two Medea adaptations. Luis Alfaro’s Mojada: A Medea in Los Angeles (directed by Laurie Woolery at Yale Rep) and Kate Snodgrass’ The Art of Burning (directed by Melia Bensussen at Hartford Stage). The first sets the action in the Chicano communities of East L.A., the second in the suburbs of a large unspecified American city, probably New York. (MoMA is mentioned). Needless to say, neither of these modern locales approaches or understands motherhood the way ancient Athens did.

Over the centuries, fatherhood has also come to be perceived differently which poses another challenge for the adapter. The father in Snodgrass’ play is overbearing, insensitive and disagreeable whereas the father in Alfaro’s version is treacherous beyond redemption. Perhaps it’s this difference which dictates that the LA child must die while the NYC child—a daughter—may live.

In Mojada, Alfaro cleaves to the original by placing his heroine in alien surroundings, making her a permanent foreigner. Euripides’s Medea is a sorceress from Asia Minor who follows her Greek husband to hyper-sophisticated Corinth. In Mojada, the whole family has immigrated from Michoacan, but Medea and her elderly servant have clung to Mexican ways while Hason and their son eagerly embrace American commerce and, much less credibly, begin rooting for American sports teams. Virile Hason (Alejandro Hernández) also embraces Armida, the ambitious and manipulative woman who employs him and ultimately seduces him (played with suitable upwardly mobile nastiness by Mónica Sánchez). In this version of reality, opportunism, coerced assimilation and greed live north of the border. Nothing is said about Mexican drug cartels, violence and corruption.

Mónica Sánchez in Mojada: A Medea in Los Angeles.

Photo credit: Joan Marcus.

As in Euripides, much of the action is recounted, either by the old servant (Alma Martinez) or a chatty neighbor who hawks pan dulce door-to-door (Nancy Rodriguez). For her part, Medea stays put, sewing collars and dress panels at a machine set up in scenic designer Marcelo Martinez Garcia’s rendition of the family’s modest back yard in Boyle Heights, a rendition made even more claustrophobic by a pair of 27-foot-high Trumpian border walls on either side.

Alfaro places bits of the ancient story wherever they can be made to fit. Jason’s epic voyage in search of the Golden Fleece is replicated in the family’s brutal passage across the Sonora desert in the care of a cayote. The stifling truck that conceals them is stopped by Mexican soldiers who rape Medea and kill another woman travelling with them. We understand that this is an additional sacrifice that Medea makes for Hason, but it’s not clear that the extra horror adds much to Hason’s debt to her; she already killed her own brother back in Michoacan so they could leave for el norte.

Hason—whose clothes, thanks to costume designer Kitty Cassetti, get upgraded every time he appears—claims that playing along with Armida is the key to the family’s success in America. Medea doesn’t buy it. When Jason pushes “playing along” to the point of marrying his employer, Medea confects a serpent dress as a wedding present for her rival. It squeezes Armida to death. Rather unnecessarily, at this point, she also kills her son, an act of pure vengeance that would be excessive for a modern mother were she wholly human. In the last instants of the play, however, we discover that Medea is actually a Mesoamerican deity of some kind, an implacable Quetzalcoatl who commands both serpent and feathered magic and doesn’t want to be messed with.

In the title role, Camila Moreno has no trouble embodying a long-suffering and ultimately wrathful wife. Unfortunately, the role never requires her to conduct the intricate and painful self-examination that makes her namesake a tragic hero.

~

The Art of Burning benefits from being less faithful to Euripides. Snodgrass’s heroine, called simply “Patricia,” also has a faithless husband and, just like the other Medea, a special talent: she’s an abstract impressionist. Jason is smitten when he first sees one of her canvasses. But Patty, as she’s called, has a tongue as sharp as the matte-cutter she muses about using as a murder weapon. Everyone who tries to befriend her, mollify her or get her to see their side of the story gets counter-punched for their pains. She’s particularly harsh on people who declare their good intentions. Mark, (Michael Kaye) a family friend who’s offering “impartial” legal help to mediate the Medea-Jason divorce is savaged for his pains. Even the couple’s 15 year-old daughter, Beth (the wonderful Clio Contogenis) gets more correction from her mother than comfort when her first date with a schoolmate goes horribly wrong. Her husband’s new girlfriend, Katya (Viva Font) gets hers when she drops by to try and make peace:

KATYA: May I come in?

PATRICIA: There’s nothing left to steal, so…No.

With everybody’s flaws neatly exposed, it’s hard to imagine what horrible surprise remains that could push Patty to murder. The igniting spark is theatrical in the most literal sense: the night before the divorce papers are to be signed, Patty takes in Medea. The tragedy brings her to see that everything she and Jason have done for Beth amounts to training the child to be “lesser-than.” They’ve poisoned her sense of self and molded her into a pliable version of subservient femininity. Could Patty’s matte knife excise her daughter’s inherited ideas? Or would it merely end her days? Can you kill someone you love in order to save them? Can Beth live with her father or is she better off dead?

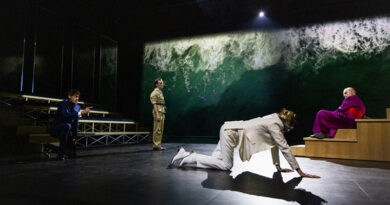

Adrianne Krstansky and Vivia Font in The Art of Burning.

Photo credit: T. Charles Erickson.

Patty has a much more involved motive for killing than simple revenge, and one that’s more in line with the Greek original. While Medea acts to stamp out a specific male line, Patty wants to stamp out the strain of generalized patriarchy her daughter has inherited. Throughout, Snodgrass doesn’t let us decide whether Patty is miles ahead of everyone where sexual politics are concerned or dangerously unstable—or both.

All this plays out on a luminous chessboard of a set designed by Luciana Stecconi and ably lit by Adja M. Jackson. When all the squares light up we see gambits offered and declined; when there’s a single square in the middle with Jason and Patty inside, we think of sumo wrestling; when characters retire to neutral corners between bouts, we think of boxing. Whatever the game, the confrontation never lets up for an instant.

As Patty, Adrianne Krstansky’s wit squirts out in quick jets like a flammable liquid. She only shouts late in the play, but she’s angry from the get-go. As Jason, Rom Barkhordar shows us a man who assumes he’s virtuous because he confesses his shortcomings, shortcomings that appall us because they’re so ordinary. Yes, Jason betrays his wife, but his glaring fault in this play is general inadequacy. He wants a new child with Katya promising: “I’ll be better this time.”

Rom Barkhordar and Michael Kaye in The Art of Burning.

Photo credit: T. Charles Erickson.

Perhaps the best sharpest moment in this splendid production belongs to Laura Latreille as Charlene, Mark-the-lawyer’s wife. When Mark accuses her of pretending to like musicals in order to please him, she lets out a superb tirade about her true taste in theatre.

All right, if you want the truth…Here it is. (BEAT.) I love Ibsen. I love August

Wilson and Arthur Miller. I love Long Day’s Journey Into Night. I want to make

love to Eugene O’Neill in that living room with the fog horns blaring and his

addict mother shooting up while his brother is falling down drunk onto the

Count of Monte Cristo. And I will beg him to put his mouth on my clit and his

cock inside me until I come all over him in a wave of rapture so deep that it

stops the tide from rising. And that’s the truth.

The Art of Burning is a comedy; Beth survives, and a child is born to Jason and Katya. Snodgrass manages this happy ending, however, without compromising the hard truths of the adults’ behaviuor.

The Medeas I saw last weekend attracted men who believe themselves to be dynamic and enterprising. They think they know what’s what. Progressively, however, these men are revealed to be less steadfast and far less talented than the women they married. Their number comes up at last—you can’t fool a Medea for long.