“Macbeth”, Shakespeare’s Globe

Neil Dowden on the South Bank

12 August 2023

Bad luck may come in threes, but the “unluckiest” play Macbeth is extending its bloody grasp on audiences five times. The Royal Shakespeare Company’s revival opens later this month, with English Touring Theatre following in September, Ralph Fiennes and Indira Varma playing the murderous couple on tour from November, then David Tennant and Cush Jumbo appearing at Donmar Warehouse in December. First up, though, is the Globe Theatre’s open-air, modern-dress, breakneck-paced production by Abigail Graham condensed into two hours of stage time. It’s an enterprising take on the Scottish tragedy though rather short on dramatic and emotional intensity.

Matti Houghton as Lady Macbeth.

Photo credit: Johan Persson.

As is the habit these days at the Globe, Shakespeare’s text has been edited – or in this case slashed – by a dramaturg, Zoë Svendsen. She has cut out passages involving Malcom’s brother Donalbain and the goddess of witchcraft Hecate (as is frequently the case in modern performances), as well as some short scenes featuring minor lords and later soldiers in the climactic battle. This is not necessarily a bad idea in order to streamline the story of what should be an exciting, action-packed thriller. (But not showing the English troops cutting down the boughs of Birnam Wood to disguise their numbers before moving on Dunsinane Castle is a mistake as this reveals how the witches have tricked Macbeth.) Also, changing some words in the Porter’s monologue, such as “equivocator” to “fake-news spreader”, gives a contemporary resonance to a set-piece that has often been done with topical ad-libbing.

In fact, the show starts with an added wordless prologue that has five singers performing a cappella to haunting effect (as they do periodically throughout) while Macbeth (Max Bennett) and Lady Macbeth (Matti Houghton) come downstage to confront the audience, with the latter cradling a blanket like a baby which she then unfurls. It’s a striking tableau that suggests the loss of the couple’s child (a “babe” is later alluded to by Lady Macbeth, but they have no children in the play). The raison d’être of Graham’s production seems to be that their unresolved grief has twisted itself into a resentment of others’ children with their distorted emotion channelled into “vaulting ambition”. Of course, the bitingly ironic thing is that after assassinating Duncan there is no chance of a hereditary succession for this childless king and queen.

Max Bennett as Macbeth.

Photo credit: Johan Persson.

In a bitter reminder, Graham’s production is awash with children. Unlike the witches’ prophecy that Macbeth “shalt be king hereafter”, Banquo “shalt get kings” – as is later envisioned eight generations down the line – via his young son Fleance whom Macbeth desperately tries to have murdered as well as his father but fails. (In a clever touch, Fleance reappears at the end of the show when Malcolm is hailed as king, as a nod to the future.) Macbeth does successfully arrange the brutal murder of his rival Macduff’s bubble-gun-firing, Spiderman-dressed son, as well as Lady Macduff deliberately stabbed through her pregnant belly, while he personally twists the neck of the English soldier Young Siward – who is here a boy. And the three apparitions conjured by the witches to give messages to Macbeth about his future are played by the boy actors already seen elsewhere.

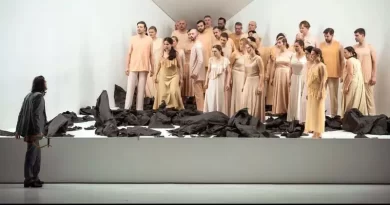

Graham’s staging is highly inventive, though not all the ideas work. A big change from the norm is to have the three witches performed by men (Ferdy Roberts, Ben Caplan, and Calum Callaghan). These “weird sisters” are played as bantering blokeish yobs wearing hazmat suits and beaked masks, a long way from supernatural mystery, and their Act IV appearance is played for macabre laughs, with the “boiling cauldron” into which they chuck body parts a liquidizer – it’s undeniably funny but as sometimes elsewhere the humour undermines the tragic mood. The same actors double as the murderers, as well as other small roles in court, and are seen trundling around with gurneys bearing body bags, so that the witches’ nefarious influence seems pervasive. Callaghan also plays the Porter – in the one section written as comic relief of course – where he jokingly interacts with the groundlings near the stage.

The build-up to the assassination of Duncan is underwhelming, lacking real suspense. The coronation banquet scene (with Macbeth for some reason dressed like Charles III) is also disappointing. Uncovering two of the long dining tables to reveal suckling pigs while under the third cover lies the bloodied corpse of Banquo works brilliantly. But the idea of having virtually no one else on stage, with the audience representing the court attending the Macbeths, doesn’t capture the disturbed public reaction to Macbeth’s guilty behaviour that suggests he has murdered his way to the throne. There is no real sense of the diseased body politic of Scotland in this production. Although cacophonous banging outside the arena drums up a martial ambience, the battle scenes are fast-forwarded with the final showdown between Macbeth and Macduff an anti-climax.

Ti Green’s stripped-back design has the stage’s infrastructure draped in monotone grey like battlements, with silver birch branches suspended above the stage and three blasted tree trunks in the yard so that the witches can stand above the surrounding crowd. Very unusually for the Globe, there is little use of musical instrumentation apart from an effective military-style side drum, but Osnat Schmool’s dirge-like score for the singers makes a big contribution to the atmosphere.

Bennett gives a lucid, clearly spoken performance as Macbeth but fails to plumb the depths of the character’s “horrible imaginings”. He doesn’t fully convey the tragic fall of a heroic soldier turned traitor to his country, while his fatalistic “Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow” speech when reacting to his wife’s death doesn’t convince us of the intense emotional journey Macbeth has undergone. Neither is there a strong sense of the disintegration of his relationship with Lady Macbeth, played energetically if in a slightly overstrained way by Houghton as an independent, assertive woman urging on her indecisive husband who mentally collapses when she realizes there will be no end to the bloodletting. The pathos of her sleepwalking scene is undercut by her grabbing a water bottle from an audience member to vainly cleanse her guilty hands, a gimmick too far.

Tamzin Griffin does well in her gender-swapped role of Queen Duncan, white-robed in naivety – a seriously bad judge of character. Fode Simbo is a touchingly paternal Banquo (distracting Fleance with a telescope to look at the stars while he gently takes away his mobile phone). We can feel the gut-wrenching grief of Aaron Anthony’s Macduff when learning his family has been wiped out, and also the fear of Eleanor Wyld’s Lady Macduff (also seen earlier with her son at the Macbeths’ castle) when the assassins break in to her unprotected home – before they become the latest victims to be carted out on gurneys.