“Hamlet” at the Lyttelton, National Theatre

Jeremy Malies on the South Bank

5 October 2025

★★☆☆☆

“I’ll lug the guts into the neighbour room …” says Hiran Abeysekera playing Hamlet. The corpse of Geoffrey Streatfeild as Polonius has landed fortuitously on a trolley and there is a delay before Abeysekera realizes that he needs to kick the brake off one of the wheels. This summed things up for me; I often wanted Robert Hastie to put the brakes on this poorly thought-through Hamlet.

Tom Glenister, Geoffrey Streatfeild and Francesca Mills.

Photo credit: Sam Taylor.

Recently appointed deputy artistic director at the National Theatre, Hastie (former artistic director of Sheffield Theatres and responsible for the wonderful Standing at the Sky’s Edge) makes a clever start as he has court retainers see the ghost of Old Hamlet (Ryan Ellsworth) not on the castle ramparts but in a banqueting chamber across the famously wide Lyttelton stage. Costume design by Ben Stones has Ellsworth as a red-bereted paratrooper. Stones, who emerges with credit from this, is also the set designer and the backcloth created by Daniel Radley-Bennett features trees that you fancy Ellsworth would have parachuted into during the civil war that has been raging in Denmark. So much, so innovative and logical. And yet from here on in, what a falling-off was there!

Abeysekera has starred in Life of Pi (winning an Olivier Award) and The Father and the Assassin (at the National Theatre, directed by its new artistic director Indhu Rubasingham), as well as playing Horatio to Paapa Essiedu’s Hamlet for the RSC in 2016. He has taken a conscious decision – he must have been indulged in this by Hastie – to play Hamlet in a knockabout and doolally (almost gurning) manner from the off. But this makes nonsense of the prince telling us some way through that he is going to “put an antic disposition on”. I thought of the maxim in the play that, “Words without thoughts never to heaven go.” Only when debating constantly whether the dapper Varsity-looking Rosencrantz (Hari Mackinnon) and Guildenstern (Joe Bolland) are spies who have been sent for by his parents to report on his behaviour did I see Abeysekera crediting his character with serious reflection.

You would fear for Denmark if it had to face an onslaught from Fortinbras (Kiren Kebaili-Dwyer) with a Hamlet of the wisecracking Buster Keatonesque temperament that Abeysekera envisages for the character. I thought a flag with “Bang!” would drop down as Abeysekera wields a pistol in one of the soliloquies. How he can put a sing-song quality into “O, that this too too solid flesh would melt” is beyond me. You would have thought that Hastie would help his actor into understanding that the speech is about suicide. It’s one of many low points. When Hamlet is asked, “… what is your cause of distemper?” the question hangs in the air because he does not appear to have a true malady.

Ayesha Dharker and Francesca Mills.

Photo credit: Sam Taylor.

I may of course be being fuddy-duddy here. There are aspects to like, notably Streatfeild who at times is embarrassingly good compared with those around him. He injects new readings into the set-piece advice to a disconcertingly clean-cut Tom Glenister as his son Laertes. Hastie brings this forward and the group have barely had a chance to suggest their family dynamic.

Would Glenister who might almost sit with the cherubim on the late-Renaissance backcloth really buy poison from a mountebank in order to cheat in the duel? Streatfeild produces gales of laughter and has a comedian’s instinct to pause and ride the merriment. Francesca Mills as Ophelia joins in the fun here as she apes her father’s stylized gestures. And Mills goes up and down the gears well. She moves from inventive schoolgirl humour as her brother warns of Hamlet’s possible sexual advances to an isolated figure in a fencing outfit and then to somebody facing annihilation as her wits turn in the mad scene. The men squirm as she approaches them with her flowers and herbs. Earlier, Mills has her character vacillate with great precision when returning the prince’s love tokens.

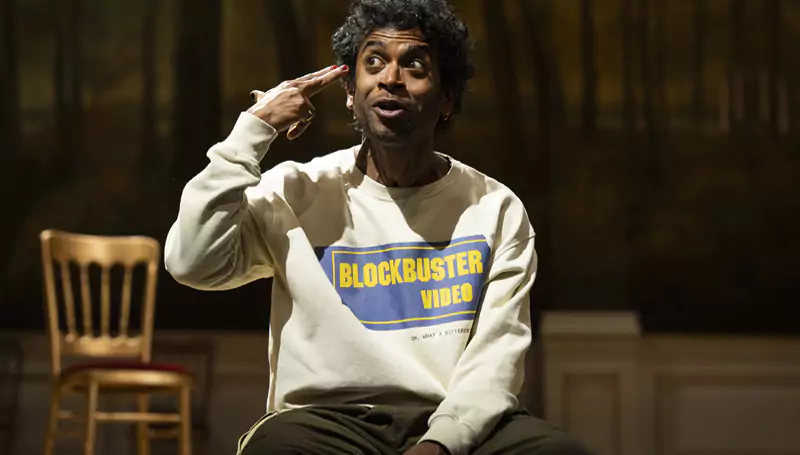

The setting? I never got a handle on this. Stones has Hamlet don a 1980s Blockbuster Video sweatshirt and yet Polonius’s family take a selfie with a flip-up phone. Perhaps it’s timeless? The backdrop does coalesce as a society, and a mirror is indeed being held up to nature.

Composer Richard Taylor makes much use of ominous recorded strings from the Carducci String Quartet that could easily be the castle ramparts heaving in a storm. Sound designer Alexandra Faye Braithwaite gives us the general atmosphere of carousing under libertine Claudius (Alistair Petrie) and fireworks that seemed to be coming at us from the Thames outside.

I’ve never seen a Hamlet where all of the characters are so conscious of the audience and it’s an aspect that Hastie drives through consistently and with invention. Claudius at his prayers in the castle cinema is a strong example. But he is reflecting on a truly woeful version of “The Mousetrap” in which the Players (suggestive of the hangers-on in Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem but without the charisma) have plodded through the text with minimal movement standing at microphones. They are an uninspiring bunch with Siobhán Redmond (as First Player) making no impression in the exchange with Abeysekera as to what Hamlet wants to hear from Aeneas’s tale to Dido. It should be tender, metatheatrical, and linguistically alive. Here it’s leaden.

No voice coach is credited; there should have been one if only to stop actors (even Mills is not free of it) committing all the errors including semaphore gestures that Hamlet warns of in his Advice to the Players. At other times the cast could be more animated. I think I would ask a waiter not to put ice in my drink with more gusto than Petrie telling Gertrude (Ayesha Dharker) not to drink from the poisoned goblet.

The production is pacey at two hours and 50 minutes. It’s already slated for National Theatre at Home and variants through which it will be shown to curriculum audiences. I shuddered when I saw an excited school group in the interval and worried that this would be their first exposure to the play.

“A hit? A palpable hit?” No, not in this incarnation and Denmark became a prison for me. Had I not been on a reviewer’s ticket I should have left at the interval. And yet the play is still there for another creative team. It is I suppose a viable experiment for an actor playing Hamlet to emphasize the almost vaudeville elements that Abeysekera chooses to work with exclusively. And the clown who wants to be a tragedian is a known form with much history. But this whole endeavour is low-octane.