“Hamlet”, Chichester Festival Theatre

Jeremy Malies in West Sussex

18 September 2025

★★★★

Sarah Bernhardt appeared as Hamlet in her sixties and Ian McKellen (admittedly in a self-aware playful production) took on the role at the age of 82 in Windsor. So at 48, Giles Terera is a stripling.

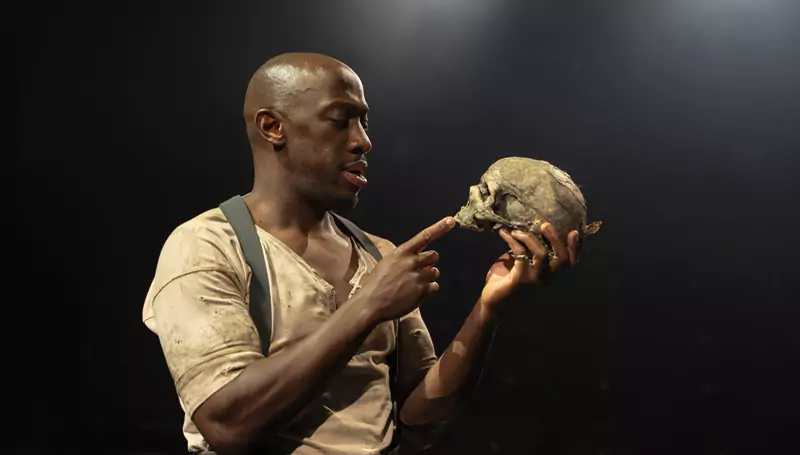

Sara-Powell, Aryion Bakare and company.

Photo credit: Ellie-Kurttz.

Hamlet tells Horatio that “Readiness is all” so Terera, who was hailed for playing Othello in a monochromatic staging at the National Theatre in 2022, will no doubt have been absorbing advice from good judges leading up to this. You would never have bet against him playing a role that Clive James identified as one which defines actors not just as performers but as human beings.

Terera is at his best here not in the huge introspective soliloquies but when he is communicating something specific to others such as the advice to the Players, telling the Player King where he should pick up a speech in Aeneas’ tale to Dido, or explaining to us how the scheme to expose his father’s murder at a play came about.

People often misread what is on the door of the principal dressing room in the Festival Theatre. It’s not the number “0” but “O” for “Olivier” – the first artistic director of the Chichester Festival in the early Sixties and of course a famous Hamlet on stage and screen. But there has never been a production of this play at the Sussex venue so artistic director Justin Audibert is showing courage in taking it on for his third season.

You would think Audibert was to the manner born with this fluid though rigidly textual version (voice and dialect coach Stephen Kemble) that has no time setting and makes us focus on the huge existential questions. Even so, when Hamlet looks to the next phase of civil war in Denmark and predicts “the imminent death of twenty thousand men” I imagine that many in the audience reflected that the Doomsday Clock assessing global warfare risk is currently set at 89 seconds to midnight.

Only Pre-Raphaelite Eve Ponsoby as Ophelia (with auburn hair, floral motif dress, and first seen in a gilt-spattered chamber) is evocative of a period. Her mad scene is excruciating and as painful to watch as anything since Helena Bonham-Carter did it in a straitjacket on screen for Zeffirelli opposite Mel Gibson. Even the bawdy singing – a pitfall for many – is no obstacle for Ponsoby.

Otherwise, Audibert does not anchor things so that the presentation is uncluttered with minimal distractions from the philosophical debate. Hamlet reads a book with a plain marble cover and composer Jonathan Girling has a church choir sing generic a capella with elements of folk and plainchant. I would defy anybody to put a time setting on this with costumes (Isobel Pellow) being vaguely late-Victorian or Edwardian. Only Fortinbras (Ozzy Aigbomian) has a distinctive outfit, and he looks like an East African dictator in uniform.

But is Denmark, in this set by designer Lily Arnold, in any way a prison? I wondered about layout. For “The Mousetrap” the royal couple and courtiers are way upstage on a platform with the dumbshow being acted in front of us on the mini thrust stage, and this takes from immediacy and tension. Audibert and Arnold might have gone full-on for a studio set-up with Hamlet being truly bounded in a nut shell. But of course “platform” is mentioned in the opening stage direction, so an upper tier makes sense.

The setting is multi-purposing with the Elsinore ramparts doubling as the graveyard where Beatie Edney as the First Gravedigger points to the extra meanings without being mannered. All of the physical comedy here with skulls, bones, and slippery ground ignites. Elsewhere, Elsinore is a scary place and the interrogation of Hamlet (while bound to a chair) by Claudius and Osric is full of menace. At times I felt I was indeed being “distilled almost to jelly”.

Terera is a team player and never absorbs the oxygen of those around him. He and Ponsoby are tactile, and I’ve rarely been so convinced of their intense backstory or pondered what a great future they might have had. As a result, Sara Powell playing Gertrude (she is lucid, steely, and crystalline in her verse-speaking) proves all the more affecting when saying that she had hoped to deck a bridal bed for the couple.

The sound design begins and ends with a sea fret lapping at the castle and does much to make the unseen voyages to and from England credible. Lighting by Ryan Day is often billowy fog through which a truly solid corporeal Ghost (Geoff Aymer doubling as Player King as is the norm) melts in and out. Like everybody else, Day is driven by the text. As the Ghost speaks of his fear of light from glow-worms, the set is suffused with tiny red aluminized reflectors.

Only Keir Charles as Polonius fails to impress, and he makes little impact even with the set-piece open goal that is the life wisdom speech to Laertes. By contrast, Ryan Hutton playing Laertes is formidable. He is physically imposing and charismatic, and you wonder why he can’t simply win at the odds in the duel without the skulduggery dreamed up by Ariyon Bakare as Claudius.

Audibert follows quite a few modern trends such as having the interval with Hamlet debating whether or not he can attack Claudius while he is at his prayers. A cliffhanger for young theatre-goers perhaps and certainly not a problem for veterans.

The take on things here is never formulaic. I was pleased to see a production that does not overdo the eavesdropping theme. And I liked the African drumming in Ed Clarke’s sound design but feared (to the extent that I’m rooting for this dysfunctional family) that a spy might be using drumbeats to give information to Fortinbras.

Terera won an Olivier for playing compulsive duellist Aaron Burr in Hamilton. An indictment for duelling didn’t stick to Burr but the general controversy ended his public life and he trod water for decades. The play here has Terera losing a duel, but we know that this performance will usher in a new dimension to his high-octane career.