“Filetstücke”: Michael Alexander Müller

Hans-Jürgen Bartsch in Berlin

8 April 2021

The Vaganten Bühne, an intimate hundred-seat theatre tucked away at the end of an alleyway underneath a movie palace, is known for the diversity of its repertoire, ranging from classics to contemporary drama. Its latest creation Filetstücke (literally Tenderloins by Michael Alexander Müller was scheduled to open in April but fell victim to the extended lockdown. With foresight the theatre had prepared for this eventuality: it accepted advance bookings for live and for live-streamed performances and, when it was certain it would not reopen in time for the first night, invited spectators to watch the play online via live-stream. This is what I did.

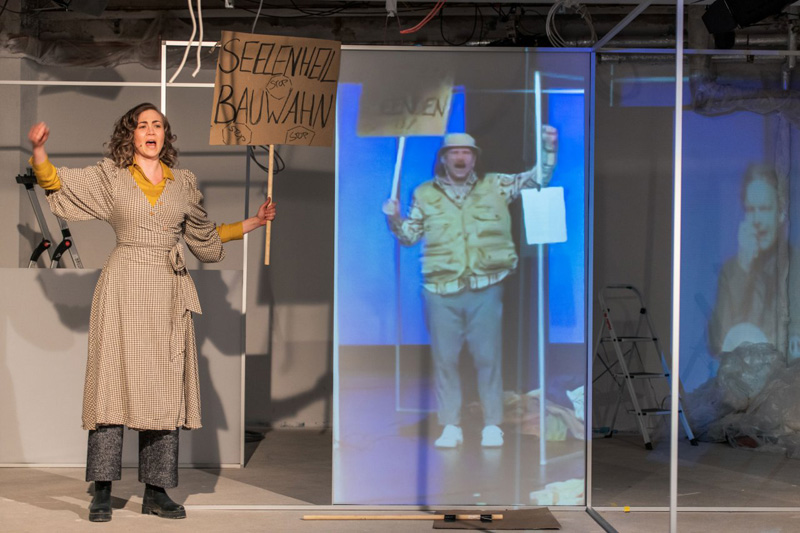

Photo courtesy of Monsun Theater.

Given that this is a play about a progressive architect struggling with conservative villagers for permission to build a modern housing estate, the choice of title is baffling until we realise that Filetstücke does not refer to tender cuts of beef but — in the figurative sense — to prime plots of land. (Filetstücke as a synonym for high-quality synonym for high-quality Grundstücke). The play, devised and directed by Johanna Hasse and Francoise Hüsges, is co-produced with the Monsun Theater in Hamburg where it would have been on show in parallel. In their advance publicity, the theatres described the joint enterprise as a “hybrid” meaning that the central theme – modern architecture in conflict with traditional attitudes – is the same on both stages, but the story lines are different. At the Vaganten, the young architect Drewes (Felix Theissen) and his business partner Feldmann (Andreas Klopp) plan to construct villas and a luxury hotel for affluent holiday-makers from the nearby town; in Hamburg, the manager of an old theatre, Frau Kleinhaus (Rilana Nitsch), wants to renovate the derelict building and convert it into a modem cultural centre. To emphasize the interconnection between the two versions, Frau Kleinhaus makes brief appearances on the Vaganten stage — in person or by video link — to consult her friend Drewes who designed the reconstructed theatre for her. Ample use is made of modern technology. We watch the actors on stage or in recorded videos and films on a screen.

Photo courtesy of Monsun Theater.

As interesting as this concept is, its implementation on stage is less so. lt’s not the fault of the Klopp-Theissen duo. Their valiant efforts to keep us interested in the story cannot distract from the fact that this play suffers from two shortcomings: there is no plot to speak of — hence no thread to follow — and there is almost no dramatic action. What we get here is a series of short scenes keeping us informed about every stage of the building project: the difficulty in finding investors: the struggle with bureaucratic procedures for obtaining permission to build the housing estate, fell old trees for a road enlargement and demolish a crumbling barn to make room for a car park. Each proposal provokes fierce opposition from the local community and environmentalists. Klopp and Theissen take tums playing the protagonists: the mayor and members of the village council, the head of the tourist office and the manager of the adjacent nature reserve. In the end, Drewes is fighting alone: his partner has been lured away to a better-paid job in London and Frau Kleinhaus has renounced their friendship. But there is a happy ending. To the tunes of a brass band, Drewes celebrates the completion of the luxury hotel and the end of his seventeen-year long struggle, chronicled here in less than two hours.