“Far Away” at Ambika P3

Tom Bolton in Central London

8 August 2025

★★★★★

The last major production of Far Away, directed by Lyndsey Turner at the Donmar Warehouse, was brought to a premature conclusion by the Covid pandemic – exactly the type of global environmental disaster that lurks in the background of Caryl Churchill’s terrifying masterpiece. Since its premiere 25 years ago, the reputation of Far Away has grown slowly but surely, and playwrights like Alistair McDowall cite it as a key text. Prescient, deeply disturbing, and naggingly unforgettable, it is probably time to acknowledge it as a 21st-century classic. Now it has been revived as part of the 2025 Camden Fringe.

Photo credit: Ellie Kurttz.

Rebecca McCutcheon’s production, for her company Lost Text/Found Space, is staged in the astonishing, cavernous depths of Ambika P3. The venue, a supersized concrete basement below the University of Westminster’s Marylebone Road building, is generally used as a visual arts venue. Far Away is thought to be the first theatre staged here, and McCutcheon is the ideal person to do it. Lost Text/Found Space specialize in site-specific productions of forgotten plays, principally by women. Churchill does not belong in the forgotten category, but it could be argued that, for the country’s greatest living playwright, she is significantly underperformed. The profiles of her male contemporaries – Stoppard, Hare, Ayckbourn – are substantially higher, but she outstrips them in originality, consistency, variety, and sheer, unnerving insight. The prophet, of course, cannot expect honour in her own land.

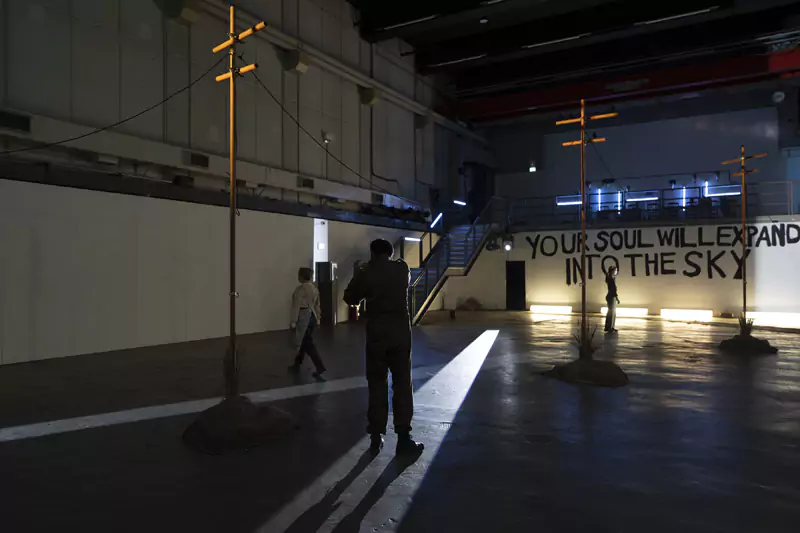

Far Away is therefore an astute choice, both in terms of its importance to the world of the 21st century, and its suitability for the venue. McCutcheon’s production is ambitious. Ambika P3 consists of a vast, windowless space, like a slightly smaller version of Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, which at first glance presents huge challenges as a performance space. However, the production makes brilliant use of the venue’s qualities. The audience is guided through a roller shutter onto a balcony overlooking a dark void marked out with telegraph poles and cut through with shafts of light (part of Jack Hathaway’s excellent lighting design). The world of the play – like a starker version of our own – is set up with a short prologue section then, at a peremptory whistle from a cast member, the audience is summoned below.

It turns out Ambika has a small warren of side rooms and curiously shaped spaces, and the play is performed across several of these. The designs, by Nicola Hewitt-George, treat these spaces like a series of installations. We glimpse a miniature landscape of earth and telegraph poles, or perhaps grave markers, and watch the opening farmhouse scene through net curtains hanging in a huge space, which later fills up with mutilated furniture. The soundscape, by Lucy Ann Harrison, sampled from ambient noises in the venue, is central to the show’s atmosphere.

Photo credit: Ellie Kurttz.

The settings, skilfully conjured, are unsettling and oppressive. The audience perches on chairs, or leans on pillars to watch, trying to come to terms with the absence of comfort, which also pervades the play. Far Away takes place in three scenes across different settings and times, written with a taught focus that does not waste a single word.

The first scene, with a young girl, Joan (Lorna Dale), and an older woman, Harper (Lizzie Hopley), talking in the kitchen, is an astonishing exercise in stripping away the trappings of civilization. Joan has seen something very disturbing, and Harper’s explanations change as she realizes how much the girl knows, smoothly expanding normality to encompass the most brutal acts. Hopley plays Harper with a rural accent – Shropshire, perhaps – which creates a false, motherly reassurance. Dale is totally convincing as a 14-year-old, doubling the role with the older Joan who appears in the later scenes.

The play then moves to a hat factory, where Joan works with Todd (Samuel Gosrani) making hats for a surreal competition which is gradually revealed as something spectacularly dark. At its 2000 première, this scene seemed to comment on the Balkan Wars, but its violent public spectacle has since become entrenched in culture through shows such as Hunger Games and Squid Game. Churchill’s laser-focused satire is balanced against short exchanges between Todd and Joan as they become interested in one another. Their sweet, spiky relationship is played subtly and persuasively by Dale and Gosrani.

From the balcony, we return to the side room and a post-apocalyptic future in which nature is siding with nations in a series of ludicrous but genuine conflicts: the elephants work with the Koreans, the cats are on the side of the French, and it is no longer acceptable to hate deer. It is filled with frenetic, climate-crisis paranoia, and has one of the boldest, most confidently abrupt endings in theatre.

Far Away conjures the dystopian future it seems we now occupy with an eerie foresight. McCutcheon’s production is truly immersive, plunging us into an environment where everything familiar suddenly seems strange and different, and we are confronted with ourselves. She makes the venue serve the play in a highly effective way, and her use of the huge central space, where scenes are prefigured rather than enacted, is ingenious. The show is a very high-quality piece of work: important, valuable drama presented in a way that means the audience will find it very hard to forget. Churchill’s work continues to prove its worth by showing us the things we can no longer see because we have forgotten that, once, they were not normal.