Erl Passion Play (Passionsspiele Erl) reviewed by Adam J Sacks

Adam J Sacks in Austria

14 October 2025

The Passion Play is original living theatre, a ritual of belief, an underlining of community and of course the theatrical chronicle of the last week, death and Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth. The oldest example in Europe is 422 years old and takes place every six years in Erl, Austria, just now having completed its five-month run. This story has been told for millennia, and its transition into theatre goes back to the first living nativity scenes, some (it is believed) started by St. Francis in Greccio in 1223.

Photo credit: Adam Sacks.

The Passion Play can be counted as Europe’s first major theatrical endeavour since Greek tragedy. Even with an interim period of 1,500 years, it bears many marks of ancient Greek theatre. Earliest mentions of the Passion Plays in the Alps region during the early 1600s usually refer to the genre as “tragedy”. Indeed, the form emerged out of the marital conditions and plagues of the Thirty Years’ War which ravaged Central Europe between 1618 and 1648. The central dramatic crux of this Catholic Passion play is the death of a child at the hands of its parents, as found in the Oresteia trilogy and Medea, and the drama of denial or recognition of Divine Incarnation as most clearly seen in the Bacchae of Euripides.

Monumental folk art

The Passion Play is also one mammoth piece of folk art on a monumental scale. At Erl, thirty percent of the town is involved and not just as actors as almost every role is cast for two. Most of the sets and costumes are also handcrafted by locals for whom the interval between iterations is more than necessary. Such infrequency also helps to retain novelty and sets the play apart from any regular programming season or schedule. The recurrence every half decade or so more resembles a religious pilgrimage, subverting any facile boundary between theatrical make-believe and the “true myth” of religious ritual.

The production in Erl is distinct from its slightly more renowned neighbour in Oberammergau across the border in Bavaria. Erl is actually older, performed more frequently (every six instead of ten years) and unlike Oberammergau it does not deliberately eschew advanced technology. Oberammergau still manages to convey an antique feel of the open air with a massive airplane hangar style theatre largely using natural light and exposed to the elements.

Photo credit: Adam Sacks.

There are no spotlights nor really any lighting design to speak of, nor is there any advanced amplification for either orchestra or actors. Erl by contrast feels like a moving film set in full surround. The role of the music this year puts this contrast in ever sharper relief. The talents of composer Christian Kolonovits, author of the score for the film North Face were retained by the production for the first time. An Austro-pop master and leader in the field of pop-orchestral crossover, most notably in his work with the German hard rock band Scorpions, his soundtrack (played by 40 orchestra members all either born or now living in Erl) is embedded inside the staging and provides a narrative arc as significant as the newly written text itself.

The actors have confirmed that the music provides the drama of living film, and supplies a constant pulse to enliven their acting. The music also aids the many contrasts and flashbacks also more typical of film technique, the stormy interludes that provide the backstory for John the Baptist or Jesus as a child.

The presence of microphones and electronic instruments are only the sonic tip of the iceberg when it comes to the marked ideological and theological clash between the two productions. Erl is adamantly modern in its techniques but also defiantly traditional in its treatment of plot and characterization, if at a much quicker pace. What was once six hours now takes around two. This is the Passion Play as a modern but unreformed tell-all.

Greta Thunberg omnipresent

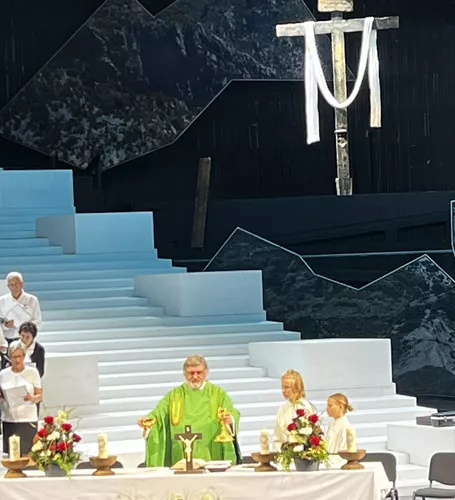

Indeed, every Sunday on a stage that is the largest parterre in Austria, the production is preceded by a Mass. The priest is quick to point out the similarity in content between his mass and the Passion Play. The relevance he implies is not about historical accuracy but getting the fundamentals right. Indeed, many of the liberties taken by this production are in the service of what a true believer might already hold close to their heart. For instance, whenever an angel is mentioned in the Bible story, this production chooses the figure of the Jesus child, as it stands for truth and guiltlessness. This theatrical decision creates some notable curiosities such as the restorative chalice that is supernaturally delivered to Jesus during his suffering is conveyed by his younger self. A similarly dramatic use of the child, is an entirely new character, a nameless, activist young woman who in Scene 5 confronts Pontius Pilate saying, “You live in a world that belongs to the children.” Affecting, but curious, this seems to relate more closely to Greta Thunberg than anything inside the Gospel texts.

The theatrical third rail for any Passion Play is the lingering legacy of Supersessionism or theological anti-Judaism. There are notable attempts in Erl at some form of reparation, from the use of oriental pop to klezmer music or the repeated singing of the Jewish hymn “Shalom Aleichem”. That song is actually limited to the welcoming of the Sabbath, and thus like the production’s use of pitta bread for matzah at the Last Supper, it comes only close to the mark. Oberammergau’s recent production reframed Judas as a secular revolutionary, while in Erl the audience may revisit a classical staging of a greedy traitor.

In some ways more disturbing than the source text itself, the entire Sanhedrin (Jewish legislative and judicial assembly) is shown throwing silver pieces at Judas and then proceeding to pat him on the back. The High Priest even embraces him around the stomach. Despite such elements, this Passion Play remains a singular instance of stage performance as folk art and may be one of the few places anywhere where you can see grown men in lederhosen crying in the theatre.

Details of Adam J Sacks’ book on the Passion Play of Oberammergau are here: https://mellenpress.com/book/Adam-J-Sacks/9848/

and his podcast can be found here: https://rss.com/podcasts/musicandpolitics/2179600/