“Endgame” at Ustinov Studio, Bath

Simon Thomas in South West England

11 September 2025

★★★★★

Lindsay Posner’s new production of Endgame at Bath’s Ustinov Studio opens with a bang, drawing us immediately into Samuel Beckett’s darkly humorous world in a way that’s probably never been seen before. Jon Bausor’s sombre designs evoke a Renaissance painting cut through by Charles Balfour’s chiaroscuro lighting. Dimness clings to the sloping walls within a wonky picture frame and our senses hardly recover from the initial onslaught. What follows is an evening of riotous and unforgettable imagery, both verbal and visual.

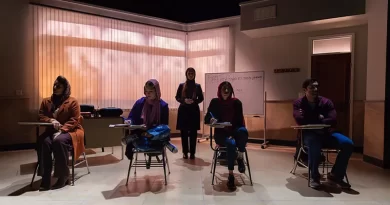

Clive Francis as Nagg.

Photo credit: Simon Annand.

Endgame, Beckett’s second published play (after Waiting for Godot), first performed in French as Fin de Partie in 1957, usually comes across as his most austere stage work. Despite its short length (90 minutes without interval) it can seem to go on forever. It abounds with in-jokes (“Will this never end?”) so Beckett was fully aware of what he was putting his audiences through. At one point during his self-directed production of Not I at the Royal Court in 1973, he instructed Billie Whitelaw to bore the audience to tears. With Endgame, there’s a danger of doing that in an unintended way.

Certainly the play is full of laughs, of the grim Beckettian kind (“there’s nothing funnier than unhappiness”), but Posner’s production fills it with vitality and energetic action, despite the static situation of the characters. The famous dustbins (in which Hamm’s parents Nell and Nagg are imprisoned in a bed of sawdust) are modern-day plastic wheelie bins set well downstage and embedded in piles of coal. There’s very little colour in the stage picture, just splashes of dim red in the main pair’s costumes, but it somehow looks rich and resonant.

A quartet of virtuoso performances at times resembles cartoon characters (Dick Dastardly comes to mind) but it never goes too far. As the “accursed progenitor” Nagg, Clive Francis is pitch-perfect, ragged and broken-down, while Selina Cadell in her brief appearance as his wife Nell injects some emotional, almost sentimental, content. Given their current pitiful condition, their memories of earlier happier times, rowing on Lake Como, and attempts to kiss while confined within their bins are heartbreaking. Mathew Horne maintains a bent and fractured posture throughout as the unfortunate factotum Clov, scurrying around the stage (the only character who has any independent movement) with his perilously leaning stepladder. Horne, whose reputation rests on much lighter comedy, shows an adeptness for darker matter, as he did in the Ustinov’s Pinter double-bill last year (The Lover/The Collection).

At the centre of both the play and the prison of a room is a towering performance by Douglas Hodge as the chair-bound despot Hamm, pathetically barking orders and endlessly whingeing while adopting a wide variety of voices and personas. He’s ranting and spiteful, grandiose and petty, petulant and wheedling, a ruined child of a man. You can believe he was once a man of stature but this wretched life has worn him down until he resembles Francis Bacon’s screaming pope, melting into his chair in a welter of frustration and despair. He seeks comfort in a stuffed dog with a leg missing (funnily enough, at an early stage of writing, Beckett described the play as a three-legged giraffe) before flinging it away in a tantrum of tyrannical anger.

The seemingly unequal power play between servant and master is explored to the hilt, Hamm dominating much of the time but ultimately at the mercy of his malevolent carer who withholds all balms to a wretched existence. Like Godot’s two protagonists, Clov longs to leave but is unable to do so, tied to this earth and doomed to haunt Hamm forever. There is no endgame, just a returning cycle of suffering.

If that doesn’t sound like a recipe for great entertainment, rest assured the frantic pace of Posner’s production, and the wild variety of Hodge’s performance, keeps us enraptured and laughing throughout, and shows that Endgame is truly great theatrical material.