Antony and Cleopatra at the Globe Theatre

Simon Jenner on the South Bank

15 August 2024

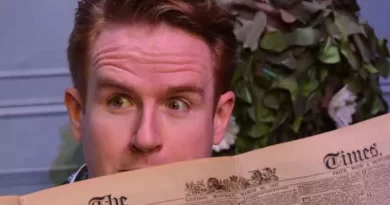

“Go to, then. Your considerate stone.” Enobarbus is silenced. Yet here, in this first production in ten years of Antony and Cleopatra at the Globe directed by Blanche McIntyre, there’s two cultures separated by two languages on stage: one is spoken. Egypt’s is realized in British Sign Language (BSL), associate director Charlotte Arrowsmith and BSL consultant Daryl Jackson working with caption co-designer Ben Glover and Sarah Readman to project words on several eminently readable screens (different fonts for Rome and Egypt). One in red and white perches above the balcony; itself used in one of the two best set-scenes, at Pompey’s boat party.

The ensemble.

Photo credit: Ellie Kurtzz.

This is easily the most comprehensive integration of BSL and spoken language I’ve seen in the theatre. Whereas Rome’s voluble words are carved in air like inscriptions by cast members, Egypt’s is designed with eye-catching intimacy. There are new gestures for death (an Anubis sign, not the standard gunshots) and signals that work, particularly if you’re in front of the stage. Sightlines and some pillars can obstruct this and occasionally the action.

A third language, Tim Sutton’s music, with an ancient horn and trombone ensemble led by Joley Cragg, is sparingly yet tellingly used sequences of flourishes, with comic timing.

Nadia Nadarajah commands as Cleopatra throughout. Her gestures ring out: though non-BSL readers won’t make out signing words Nadarajah’s actions and looks are unmistakable. This comes into painfully comic relief when Nadeem Islam’s Mardian is beaten up for bearing bad news (elsewhere he plays put-upon eunuch Alexas).

Mark Antony (John Hollingworth) is a match for Nadarajah, exuding dispatch and energy, a relatively youthful Antony with the glow of Philippi still upon him and the smart of Octavius Caesar’s ascent like a slap he’s not yet recovered from. As if echoing Cleopatra’s jibe about “On a sudden a Roman thought hath struck him”, Hollingworth snaps into them when meeting Romans. His body stiffens, his gestures quicken. The absence of BSL in this world means everything goes clean to the word where nuance is lost.

Excellent in this too is Bert Seymour’s lean and watchful Octavius, trying not to prowl and pounce; weighing his utterance like light stones. Peter Landi as Lepidus exudes his character’s lack of gravitas not in any foolish action. An outward dignity slips on conciliatory nostrums. The party scene with his drunken slurs omits the latter self-betrayal, replaced with egging-on cheers.

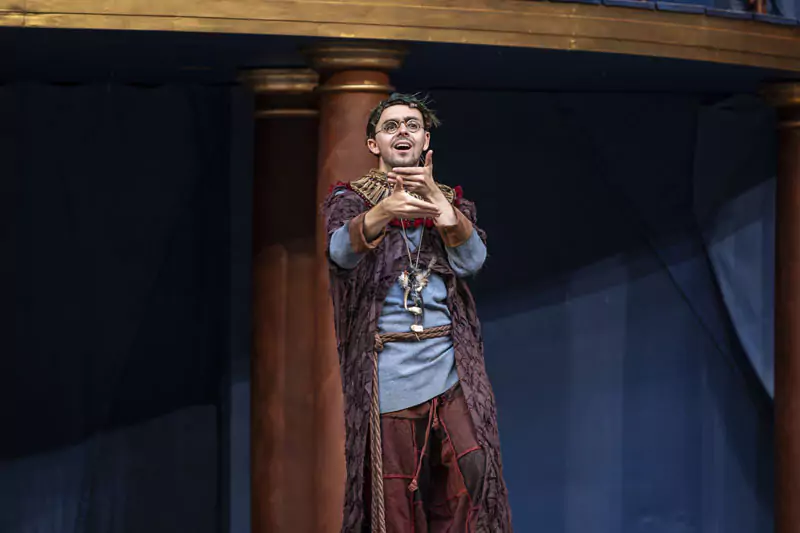

William Grint as Soothsayer.

Photo credit: Ellie Kurtzz.

Mark Donald’s Dolabella brings a warm tinge to Roman policy with a clarity the character doesn’t feel. Esther MacAuley’s Agrippa, who comes up with the Octavia marriage bonds well with both Enobarbus and Pompey. As piratical Menas, McAuley is exuberant in a cut-throat proposal, exasperated with Pompey’s finessing of conscience. As Proculeius, McAuley confides to Cleopatra the warning Dolabella should have given. Though the underscoring “Make what use of this you may” is lost. Some oft-cut badinage remains in this two-hour 45-minute staging, where some better-known lines go.

Daniel Millar’s Enobarbus is consistently watchable, with his keen-eared weariness correcting Roman assumptions of Antony, yet palpably torn between the two cultures. He naturally ends splitting his heart. Millar’s description of Cleopatra’s arrival allows him to rise octaves in a scale of praise, and descant on wonder.

It’s Enobarbus who predicts that Antony’s marrying Octavia will hasten disaster. Gabriela Leon straddles both worlds of BSL and spoken: as Iras always second to Charmian, she exudes frustration. As a pained Octavia the weight of political marriage, with hopeful accommodation followed by betrayal, allows McIntyre to etch the degree to which Seymour’s Octavius can even empathize with what he’s wrought. As Antony-whipped Thyreus, Leon completes a trilogy of the most effective multi-roling on stage.

Gabin Kongolo as Pompey exudes a lithe presence, the nearly man lacking ruthlessness. William Grint using BSL mostly, and a few explosive words, is riveting as Soothsayer, Clown and Soldier as well as Diomedes: each role a shiver of foreboding. There’s Roman work from Rhiannon May and Tom Simper, particularly in exchanges with Enobarbus.

Zoë McWhinney as Charmian builds her role from playfulness to a detonation of silent grief at Iras’s death. It’s electrifying as it is revealing. Before this McWhinney brings out Charmian’s mischief, though even here she shudders learning from the Soothsayer she will outlive her mistress. After, she plays only to adjust Cleopatra’s crown.

Another set piece with choreographer Mark Smith is the reduced battles scenes enacted as the briefest of ballets, where Rachel Bown-Williams and Ruth Cooper-Brown’s fight and intimacy co-ordination mostly isn’t needed. Love and violence happen off the battlefield. A few grand costumes aside, Simon Daw’s design extends to unfussy minimal attire, and a balcony swathed in blue cloth setting off the screen but allowing an abstraction from Pompey’s sails to battlegrounds.

The production hinges on the chemistry between Nadarajah and Hollingworth. Certainly the timing of their furious exchanges is well-caught on both screen and action. Of all moments in the play this is the most difficult of all to translate into two functional languages. Inevitably the sheer vocal clash of say Antony and Cleopatra is missing on one level, or the exuberant badinage of the Egyptian court. That can make for a certain distance. What makes up for that is warmth, stand-offs that threaten, and the gestural tenderness on the interface of speech and signing; some credit for this must go to BSL coach Adam Bassett.

Though reading the text can distract from the acting with BSL, there’s a huge gain in clarity, which can be an advantage even with spoken dialogue. There’s a case for making surtitles a permanent fixture, especially with productions using BSL or occasionally other languages. But it might not stop there. Occasionally lack of vocal clarity has been a feature of the Globe for several years, and this might address it.

A groundbreaking production, it also plays to the separation of cultures and tongues, the vast distances and epic scale of the work – itself ideally suited to this concept. It mightn’t be the most emotionally engrossing Antony and Cleopatra, nor boast the most detailed characterization – this space isn’t designed for that. But that is from the perspective of a hearing audience member. There is much I missed that others won’t. It sets a high benchmark that needs following up.