“A Tupperware of Ashes” at Dorfman, National Theatre

Simon Jenner on the South Bank

5 October 2024

“Queenie! Come in! The water is lovely!” Rarely have such clichés taken on an invitation to immersion and surrender of a Lear-like existence. Tanika Gupta’s A Tupperware of Ashes runs at the National Theatre’s Dorfman directed by Pooja Ghai until 16 November 16.

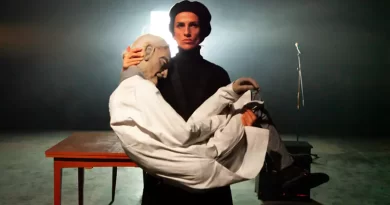

Meera Syal as Queenie.

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

In this case a mother shuttling between her three children is just the start. All these siblings though feel both guilt and intolerable pressure. Michelin-starred restaurateur Queenie (Meera Syal) is magnificent, monstrously unfair, and knows best.

Which is a challenge when Queenie doesn’t quite know what’s happening to her. The world she has built up, her CBE, her food empire, seems to be slipping. And does she own a chain with outlets in Paris and Calcutta? She’s not 65 her lifelong friend Indrani (Shobna Gulati, generating a friend’s deft values to everyone) reminds her. Queenie’s 68 like her.

Rosa Maggiora’s set is simple but dominates. With Matt Haskins’ lighting the world is both a numinous dream with skies declared blue when they’re tangerine, and a striated backdrop, which takes on creases of daylight as the wide steps across the set function as interior or backdrop to the sea; or banks of the Ganges.

In its two and a half hours this play moves seamlessly between Queenie’s increasingly detached interior and that of her children who agonize over her real (as opposed to perceived) actions in a world. A world that takes on sudden reality in Elena Peña’s screech of traffic, offset by Nitin Sawhney’s music, most evocative as Syal and her deceased husband Ameet (Zubin Varla) flirt, cajole, sun themselves, and above all dance to his renderings of Tagore, which run through this work, in Anjali Mehra’s movement direction. John Bulleid’s illusions too are as delicate as they are surprising.

Ameet though is also Queenie’s voice of reason: despite his imagined existence he sides with his children when conflict breaks out. He even restrains her. It’s an imaginative piece of stagecraft, portraying a complexity normally tangled in words. One written across the sky in stars, as it echoes streaks and tangles in Queenie’s mind.

It’s not just Ameet with his warmth irradiated by Varla like a benediction (even if he does spring his relocation to Britain in a flashback) but the children like him are up for fun. Humour suffuses Gupta’s writing here and tragicomedy sits alongside innocent (and insolent) wit. Early on, when Queenie burns the rice, the three mercilessly rag her with: “How many Bengali mums does it take to change a lightbulb?” “Don’t worry about me.” “I’ll sit in the dark.”

Meera Syal and Shobna Gulati.

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

The initiator is Kamala (Natalie Dew, fraught, briskly tender, guilty, and efficient in equal measure), the youngest and highest-achieving as a doctor about to specialize in paediatrics, with no time for herself in her fraught NHS world. Queenie insultingly can’t remember the name of Gabriel her partner. The most analytical, Kamala is also under most pressure in one shocking moment.

Eldest Raj (Raj Bajaj) is also a scapegrace, sent to an uncle at 16 for drug-dealing; now with an offstage wife Krishna whom Queenie irrationally loathes. Which is awkward as she’s now pregnant with Queenie’s first grandchild. Cruelly Queenie doesn’t react to the others’ enthusiastic congratulations, but asks if Raj is sure it’s his. Bajaj edges in both a charm and hangdog under-achiever note that suggests he might pull a rabbit out of a hat once a decade.

Gopal (Marc Elliott), whose partner Ali Queenie does acknowledge (after accepting Gopal has come out), radiates quick sensitivity and reason. After Queenie relinquishes her empire to her chief chef Jamila (first of Avita Jay’s very different roles) Queenie finds most solace with Gopal, but after escaping to her old house in Harlow and picking the lock with a hairpin, the three need to decide.

What Gupta achieves in the third act is balance of memory and desires ensuring the withdrawing roar of the world is matched by sharp inner recall and a life Queenie sees as alien. There’s fine work by Stephen Fewell as brisk specialist Doctor Young, called on by Kamala, with an unwelcome diagnosis; through other roles to Pavel who helps Queenie retain dignity and humanity through the agency of ice-cream, which turns deftly into something else.

Acutely written, vividly characterized even in tiny roles, Gupta crafts conflict as the children turn from bickering to unity to recrimination. Their own lives are challenged. After an incident one can’t take a vital exam. Despite Indrani’s claims, how far can duty go? Queenie after all didn’t sacrifice her career for parents back in Calcutta. A play detailing how a devoted family must relinquish much of what other families do without blinking is wrenching; but it’s hilarious too.

Syal leads a faultless cast and herself gives a towering performance playing off steely disdain, even cruelty, through quicksilver warmth and moments of tiny devastation.

The Dorfman seems these days almost a guarantee of something exceptional. Plays like All of Us, Grenfell, The Confessions, Infinite Life, and recently Till the Stars Come Down and The Hot Wing King magically deliver the space’s containment. A Tupperware of Ashes spells another.