“A Midsummer Night’s Dream”: Shakespeare’s Globe

Julie Sorokurs at A Midsummer Night’s Dream: Shakespeare’s Globe

27 May 2021

A revival of Sean Holmes’s carnivalesque 2019 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream marked the Globe’s return to live theatre in May. While Covid-conscious protocols were firmly in place, the show was big and brash enough to at least metaphorically fill any spaces left empty to maintain social distancing. From the inclusion of a live brass band that looked like it had been plucked out of a Wes Anderson film (dressed in all-white tops and knee-length shorts, with neon pastels colouring their caps, belts, and shoes), to a multiplicity of Pucks competing against one another to see who could weave the most mischief, this production of Dream encapsulated the American expression, “go big, or go home”.

Victoria Elliott and Sophie Russell.

Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

If the function of carnival is to upset the status quo (often through exaggeration or contradiction), then this show sometimes achieves both in good measure – especially at the start. The show begins with a fully armoured Hippolyta (Victoria Elliott) bursting out of a box marked “Fragile”, her ire towards her “saviour”/captor Theseus (Peter Bourke, dressed like a dictator who’s been dunked into a vat of rainbow sprinkles) falling on deaf ears as the latter compares their imminent union to finally receiving an inheritance.

The visual ironies continue with the two Athenian couples at the centre of the play — Lysander (Bryan Dick) and Hermia (Nadi Kemp-Sayfi), and Demetrius (Ciaran O’Brien) and Helena (Shona Babayemi) — all nearly indistinguishable from one another in their matching black and white outfits (with excellent diagonal ruffs). Contrasted against all the multi-coloured streamers and fairies made to look like ice lollies with googly eyes pasted onto them, the four are accordingly flat when all together, their lack of chemistry palpable when bookended by scenes with Titania and Bottom.

Though Hermia and Helena do well enough on their own (Babayemi’s Helena is particularly engaging as desperately lovesick in the first half of the performance and suspicious and wounded by the attention from Lysander and Demetrius in the second half), O’Brien and Dick are not convincing as the very same Lysander and Demetrius that the other two love so deeply. It was a nice touch to dress them all identically enough that they are effectively interchangeable with one another, but I’m not sure that the performances were able to hold their own as a result.

Shona Babayemi and Ciarán O’Brien.

Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

There is also the intrusion of plastic and artifice into the natural world, one of only a handful of overtly dark themes explored in this production (the audience’s amusement notwithstanding). Titania sleeps in a large recycling bin, brimming with phosphorescently coloured fake flowers. Bottom wears leopard—print tracksuit trousers and a sequined red, zebra-print jacket to match; when he is transformed, it is into a life-sized pinata rather than a “real” donkey. Lysander brings an inflatable air mattress into the woods.

The full effect of some of these visual accompaniments to Shakespeare’s prose was, however, likely lost on audiences less familiar with the play – between the duelling water pistols and Titania’s promenade around the yard in her electric scooter, it was at times difficult to make out what was being said, particularly when giddy fanfare seemed to be the order of the day. When Peter Quince (Nadine Higgin) directs Pyramus and Thisbe from behind a DJ booth, it is to the detriment of those who could neither hear nor see Quince properly. (Having said that, some of the best scenes were with Higgin at the forefront – her charisma and several rounds of lightning-fast improvisation with one of the groundlings never fails to bring down the house.)

The production consequently finds it hard to settle into a consistent tone, though – aesthetically – it most often looks like a full-on rave has pitched a tent in the middle of New Orleans (design by Jean Chan]. I’m still of two minds about the Latin-American feel of the show, the pinata especially gave me pause – celebratory it may be, it nevertheless relies on tired tropes of the associated culture knowing best about what it means to throw a big party. Crucially, magic and dreams are the definitive elements of Shakespeare’s play, so the decision to portray these through Latin-American visuals was easy at best and culturally appropriative at worst.

Nadine Higgin and Rachel Hannah Clarke.

Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

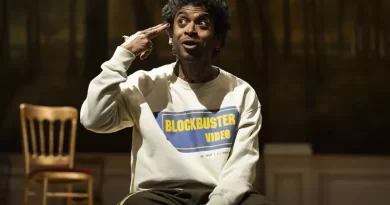

Sophie Russell as Nick Bottom and Victoria Elliott as Titania are Dream’s unquestionable stars. Russell is reliably loud and absurdly confident, at one point recalling and whizzing through every fragment of French that might be familiar to a British audience (“Voulez vous coucher avec moi ce soir?” and “Non, je ne regrette rien” being particular, if not predictable, favourites). Much like her Richard from the Globe’s 2019 production of Richard III, Russell as Bottom has the audience exactly where she wants us, and she misses no opportunity to remind us that she can see us (the occasional bouts of French a vivid example). Elliott’s Titania is similarly irresistible with her candyfloss-coloured hair and enough hauteur to fill the recycling bin she sleeps in (and she has a lovely singing voice to boot). What are easily the best scenes in the play are those between Bottom and Titania, with Elliott providing as close a match to Russell’s buffoonery as there could be.

It was odd to be reviewing what was the first show I’d seen at the Globe’s open-air theatre, as l didn’t have any other pre-Covid productions against which to compare it. Looking through pictures

Of the 2019 production (and I can’t help but note its tightly packed yard of groundlings), it does look like it was an otherwise near-identical production, albeit with a few of the parts recast. The context of this production’s return to the Globe nevertheless bears mentioning, particularly as it also marks the return of England’s live theatre to indoor spaces after it was once again shut down at the start of last year’s winter holidays.

My experience leading up to the start of the show was not much different from my one other visit to a London theatre during the pandemic just as the Bridge Theatre required in September 2020, the Globe asked that 1) all attendees arrived within an assigned time slot and agreed to a temperature reading, 2) checked into the venue using the NHS Track and Trace app, and 3) kept their masks on throughout the performance unless exempt.

The venue was filled to a significantly reduced capacity (with the audience in “bubbles” of either one, two, or three), and the show ran for just over two hours, with no interval. It was a veritable stroke of luck to catch a show at the Globe just as restrictions had been lifted to allow for performances to resume, and on a day that turned out to be a remarkably warm and sunny one. It added a real touch of magic to a production that just fell short of it. And so it was that, by the time it came to the curtain call, there was a whole lot of goodwill and gratitude emanating from the company onstage, and it was returned in kind by an equally enthusiastic and supportive audience.