“A Colónia” at Culturgest, Lisbon

Jeremy Malies in Portugal

14 July 2025

Perhaps you need to have had a twentieth-century revolution (and in living memory) to do this sort of thing well? Film and theatre director Marco Martins has worked from reporting by journalist Joana Pereira Bastos to dramatize the experiences of opponents of the Portuguese dictatorship in the 1970s during the corporatist Portuguese state known as the Estado Novo.

Photo credit: Alipio Padilha.

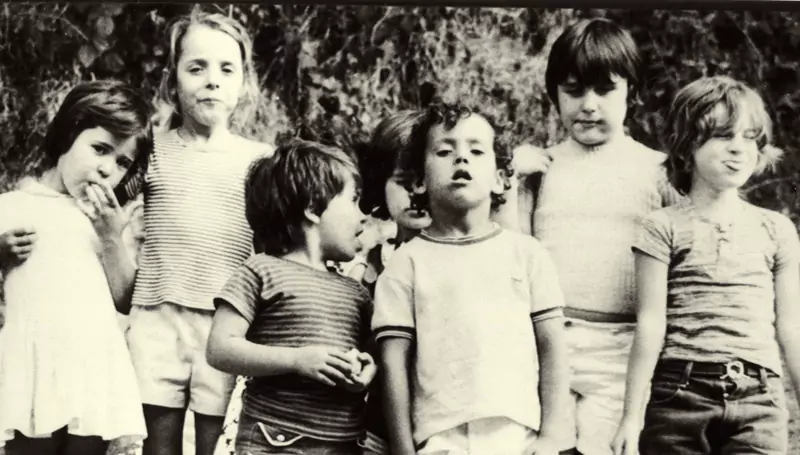

The springboard is Martins’ treatment of a holiday camp for the children of political prisoners in the summer of 1972 at a manor house in the province of Estremadura with the support of Amnesty International. Many of the children who had been living underground with extended family for fear of reprisals or surveillance had no notion of group activity and barely understood the concept of play.

Martins casts both actors and mainstream members of the public; many of the middle-aged performers are indeed the children who went to the camp. They work alongside present-day teenagers who play their younger selves. Watching two iterations of the same person merge while also digesting the political heft and torture theme (think Pinter’s One for the Road) makes this an arduous evening but the rewards are great.

Flooding the theatre with gravitas and charisma from the upper level of the two-tier set are real-life couple (and survivors of imprisonment) Dominigos Abrantes and Conceição Matos, both in their ninetieth year. As I realized that Conceição was breathing with mechanical assistance, I had to swallow hard and became a little moist and croaky. I can’t have been alone in this.

Photo credit: Alipio Padilha.

A Colónia has been revived from 2024, arrives here from Porto, and is now even more urgent. English surtitles included the phrase “echoes of the past in the present”. Ponder the fact that far-right party Chega now has 60 representatives in the 230-seat (no upper house) Assembly of the Republic and the play proves chilling. Reflect that Abrantes is a former member of the Assembly and the whole thing becomes yet more sombre. “We helped to overcome what went wrong” is Abrantes’ main reflection in an interview. Surely he could never have guessed that all this might be cyclical?

I was reminded of a broadly similar piece in Romania about the overthrow of Ceaușescu (nominally a Communist but in fact a dictator) and the threat that Romanian democracy now faces from far-right George Simion.

To describe this as “verbatim theatre” would be simplistic, and the creatives involved with the project do not like the term. Pereira Bastos’ respected journalism functions as a distilling agent on the source materials, and her human insights will have provided structure.

The topic could easily degenerate into polemic, but Martins’ stagecraft moves the piece up and down the gears. The set has two levels with Abrantes, Matos, and the middle generation characters on the top tier where we see projections of historic documents and images that have been researched by Susana de Sousa Dias.

The present day teenagers playing the prisoners’ children are on the lower level, and there is even a third component. This is a glass cubicle in which B Fachada (stage name of Bernardo Cruz Fachada) plays guitar surrounded by a youth singing group. They sing songs that were beloved by children at the time but banned by the PIDE, the International and State Defense Police. B Fachada has worked on other investigative projects and propels the narrative. There is incidental organ music varying from minimalist use of a Hammond organ to lush harmonium.

Photo credit: Alipio Padilha.

Only one segment fails. We watch the children (played by adolescents and young adults) creating beach fires in the hope of being seen by their parents in coastal fort-prisons such as Caxias and Peniche. Martins could have helped them improvise rather than relying on stilted choreography by movement director Vânia Rovisco. It’s a crucial scene and should have flown higher. There is also a bizarre piece of cross-casting in which a young male (in no way androgynous) plays Matos menstruating and without any kind of sanitary products. I guess the casting decision is a diluting or distancing mechanism but the whole section is surely misguided. I’m capable of imagining such things if they are suggested.

The cast never seem to be mimicking their historical counterparts literally; there is perspective as well as gradations and refinement throughout. Martins and his colleagues not only dislike the label “verbatim theatre” but are none too keen on “documentary theatre”. And yet this piece does not exist in a vacuum as a form. Put it alongside Talking to Terrorists, Justifying War, and Guantanamo as one of the most important and subtle pieces of theatre springing from real events and using archive material since the genre came into being.