“Mrs Warren’s Profession”, Theatre Royal Bath

Simon Thomas in the south-west

18 November 2022

A tour that takes in Bath, Richmond, Chichester, Guildford, and Cheltenham may prioritize pleasing the good people of those towns rather than frightening or scandalizing them with material that is too unseemly. That certainly seems to be the approach director Anthony Banks is taking with this new production of George Bernard Shaw’s classic 1893 play Mrs Warren’s Profession, which focuses on the cosy Home Counties comedy aspects more than the social realism swirling beneath the surface.

Rose Quentin and Caroline Quentin.

Photo credit: Pamela Raith.

A broad approach to the comedy, resembling TV sitcom at times, marks some of the performances and also the chocolate box sets (skilfully executed by David Woodhead) which lend opportunities for extraneous visual gags, such as a doll’s house cottage in the first two acts that the actors struggle to squeeze into. A similar quaintness is seen in Act Three with a miniaturized country church that the actors could almost pick up and put in their pockets, and it’s only in the final act that we eventually get a grown-up set.

The play is set firmly in Surrey and opens in familiar comedy territory of the era, with mentions of Haslemere, Hindhead, Redhill, and over the border Horsham, but very soon starts exploring much less picturesque terrain.

It’s almost impossible to discuss Mrs Warren’s Profession without revealing what that profession is. Shaw’s comedy is a springboard for an analysis of the morality of the “world’s oldest business”, and the plight of women who he said “are forced to resort to prostitution to keep body and soul together”. There is some pretty serious discussion about these moral and social issues – in what Shaw himself called an “unpleasant” play that was initially banned by the Lord Chamberlain – which just about survive Banks’ knockabout production.

This is in large part due to Rose Quentin’s forceful performance as Vivie Warren which is more believable than that of her real-life mother, the better-known Caroline Quentin, as the brothel-keeper and ex-prostitute Kitty Warren, whose veneer of social respectability is wafer thin.

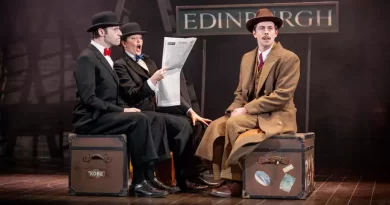

Rose Quentin and Stephen Rahman-Hughes.

Photo credit: Pamela Raith.

The older Quentin takes the broadest possible approach to characterization, dropping her aitches along with her airs and graces whenever under emotional pressure. The younger Quentin brings a much greater degree of realism to the burgeoning awareness of the character who belatedly learns everything about her mother and the world she’s been brought up in.

Kitty’s business partner, Sir George Crofts, is a pretty vicious piece of work, constantly justifying his means of making money and seeking inappropriate liaisons. His nastiness is only hinted at by Simon Shepherd in an otherwise strong performance. Matthew Cottle’s Reverend Gardner is very enjoyable but veers towards the comedy vicar beloved of television shows, while Stephen Rahman-Hughes’ dithery would-be anarchist Praed is similarly clichéd.

Peter Losasso shines as a Woosterish layabout Frank Gardner, dripping with an almost foppish insouciance. Like all the men in the play, he reveals a depraved side to his character when not he’s not up to larks. He’s quite prepared to overlook the probable sibling relationship in his romantic pursuit of Vivie.

The play is surprisingly short on sermonizing, despite some characteristic long-windedness, and Shaw leaves some scope for the audience to make up their own minds. Vivie is by no means a straightforward character. She’s a rather priggish young woman who hates the arts and is proud to declare, “I like working and getting paid for it”. Like her mother she too has a ruthlessness in her bargaining and her steadfastness in pursuing her own path means she has to sacrifice human relations for principles. Shaw gives her the law as a refuge (she flees to Chancery Lane to go into business as a conveyancer) which could be seen as no less dubious a profession than the more overt immorality of her mother’s. Had he wanted to present Vivie as a more heroic protagonist he would surely have chosen something else.

A discussion of the morals around sex work is probably as old as the profession itself and is sure to go on well into the future, making Shaw’s play constantly relevant. His message is wider than that though. When Sir George tries to justify his business by saying that the same thing happens at all levels of society, he’s showing that prostitution is just a symptom of a capitalist society which constantly sells its people short, although audiences for this production may not find it easy to interpret the play that way.