“Guess How Much I Love You?”, Royal Court Jerwood Theatre Downstairs

Jeremy Malies in West London

★★★★☆

26 January 2025

A product of Juilliard and to be seen in Game of Thrones and The Lord of the Rings, Robert Aramayo has a body of work behind him. And yet, this is his first professional stage role. It requires him to recite Yeats poetry three times, impersonate Morrissey, dance to The Velvet Underground, and read from a children’s book about hares while in a funeral parlour. Quite a debut!

Lena Kaur as the midwife.

Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Luke Norris’s play So Here We Are won the Bruntwood Prize Judges’ Award in 2013. He is now back with an extraordinary if unremittingly bleak text performed by Aramayo and Rosie Sheehy who is still vivid in my memory for The Brightening Air at the Old Vic.

Norris has an impressive record as a performer. I guess it’s because actors (until they have complete freedom over what they do) will sometimes be asked to perform stodgy dialogue that their own writing invariably proves simple, naturalistic, and idiomatic. Trippingly on the tongue as you might expect from somebody who has been in two runs of The Motive and the Cue.

Norris has also appeared in Joe Penhall’s clinic-set Blue/Orange which may have helped him with the impeccable hospital atmosphere of this piece that charts the emotions and interplay between a couple when a scan at 20 weeks reveals that the woman’s pregnancy may be compromised.

As the pair bicker, tease each other, and eventually have massive rows, the phenomenon that is Rosie Sheehy negotiates the rollercoaster relationship with the intensity that has characterized her recent role in Machinal. There are few moments that are easy watching here with total blackouts between scenes and enough mention of bodily fluids to upset the squeamish.

This is not a two-hander. There is a role, not substantial but much more than a walk-on, for Lena Kaur as the midwife who combines an Alan Bennett-ish clucking Yorkshire tone with yet more intensity as she deals with the implications (and excruciating anatomical detail) of the pregnancy problems. Kaur must have her character interact meaningfully with a couple in their dilemma while retaining clinical detachment.

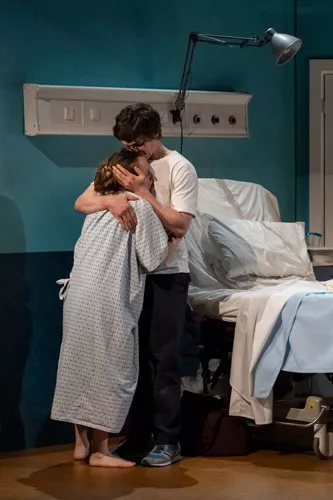

Rosie Sheehy and Robert Aramayo.

Photo credit: Johan Persson.

The blackouts catapult us between the six scenes and distinct sets by Grace Smart. These include the hospital room for a scan, side room for post-birth, the couple’s bedroom (they are only ever Him and Her), and even a holiday beach on which Smart moves from hyper-observed detail to broader strokes and a stereotypical resort.

You need to be in a neutral, perhaps even buoyant mood to ride with the punches in all this or perhaps just have more fortitude than me. I did wonder if Norris might have lightened the gloom more. Just when you think there might be some relief after good gags about the husband’s use of porn there is a heavy discussion of how women become a commodity in the male-run porn industry. The Aramayo character does have amusing quips in this section about a long campaign for freedom to sell one’s body. These work because we never lose sight of the fact that Him is fundamentally decent and given to irony. I thought of Porn Play at the same venue and the discussion of porn as (possible) catharsis for men in Slave Play.

A subtle aspect of the dialogue is the way in which the problems over moral choices take a toll on the couple’s liberal values and careful choice of words. It pains them to discuss whether their child will be “alright”. Lighting by Jessica Hung Han Yun achieves the right clinical tones for the hospital scenes. When light from a window is threatening to be overpowering, Her demands that a blind is closed because “the sun does not make any sense”.

Guess How Much I Love You? is a significant work that is technically adept and asks many questions. The plot is revealed not as drip feed but rather as large increments or stepping stones. By giving expectant couples information that was not available a generation ago, scanning technology can throw dilemmas. “What happens next is I’m a death camp …” says Her as the prognosis hits rock bottom.

Flaws? When it comes, the humour is of the highest order but there is interminable mock-serious discussion of baby names which palls quickly. At 95 minutes without an interval, the pressure cooker environment is misguided. I wish Norris could have seen fit to tread water for a while. Him is far better read and more erudite than Her, but for a moment I fancied that the couple were seeing themselves as the tramps in Waiting for Godot as they agonize over scans and updates, asking if they are going to escape a spiral that is ensnaring them. Him says, “It’s by design that things fuck up sometimes.” Both the partners are steered by events towards religion, Him to the Catholicism of his Irish family, Her to a vaguer pantheism.

Norris tells us nothing of the couple other than that they live in London and are in a lower-middle-income tier. This is a merit of the play, meaning that it will age well and not degenerate into a period piece. There is zero artifice. Audiences, in the current production at least, can focus on acting that has ferocity and intensity while remaining calibrated. A key theme is right to life being compared with quality of life. Put this with other fine dramas about medical ethics such as Caryl Churchill’s A Number, Lucy Prebble’s The Effect, and Robert Icke’s The Doctor. It’s a worthy component to the season as the Royal Court celebrates its seventieth year.

One of the three Yeats poems includes, “For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand.” I should say so! And to cap it all, there was a medical emergency in the stalls on the night I attended that halted the performance. I finally got the relevance of the Morrissey song “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now”.