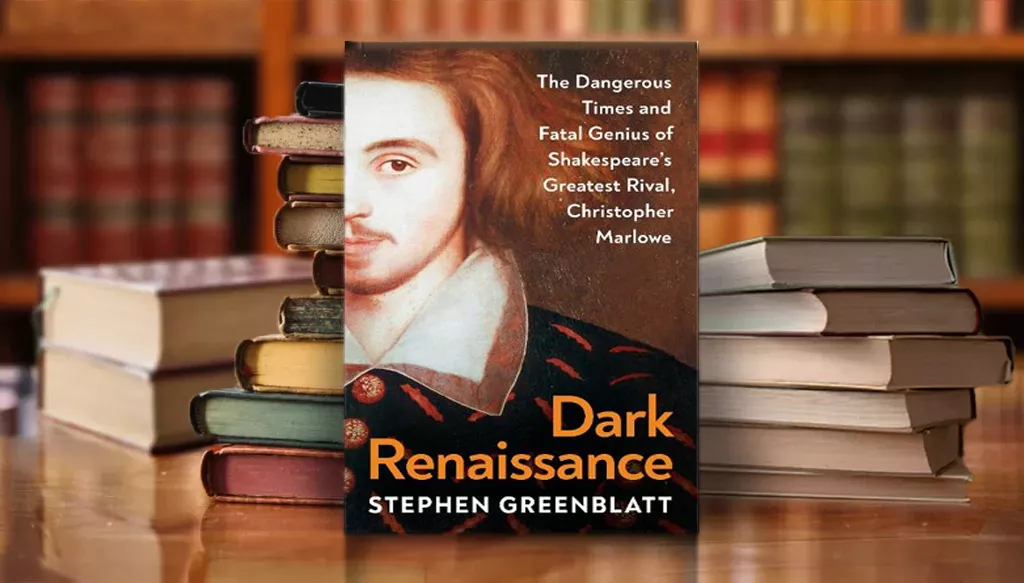

“Dark Renaissance”, Stephen Greenblatt

Dark Renaissance: The Dangerous Times and Fatal Genius of Shakespeare’s Greatest Rival, Christopher Marlowe

Stephen Greenblatt. 334 pp. Bodley Head £25. ISBN 9781847927149

I

With Stephen Greenblatt’s latest volume, Dark Renaissance, comes a lengthy surtitle like a cloak trailed in poisons: The Dangerous Times and Fatal Genius of Shakespeare’s Greatest Rival, Christopher Marlowe. Dark not just because of its subject. The title wraps itself in that cloak then dazzles us when the cloak is dropped: just like the presumed portrait of Marlowe reproduced on the cover. It’s a 1585 painting discovered on a skip at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge in 1958. It was immediately suggested (and generally accepted) as a portrait of the college’s six-year student Marlowe. The sumptuous orange and black of the most troubled and pioneering British renaissance figure steps out for a moment. His head seems uncomfortably small. Sumptuary laws would not allow a cobbler’s son such finery. It’s not just rich apparel but gaudy. Such laws were the least of Marlowe’s problems.

We know far less about the life of Christopher Marlowe than we do even about Shakespeare, his exact contemporary, partly because Marlowe lived for 23 fewer years. But also because his violent death as documented proves doubtful, and his service to the state is shrouded, as it would be, in mystery.

Stephen Greenblatt is perhaps best known recently for Will in the World, his study of “How Shakespeare became Shakespeare”, another subtitle. His style is engaging and he comes armed with praise from various theatrical grandees but, more tellingly, from James Shapiro, author of two ground-breaking but also popular Shakespeare studies. 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare and The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606. Shapiro though, equally as engaging a writer, grounds his scholarship in footnotes and has far less to speculate about. Greenblatt here confines his notes to the end of the book by chapters but in summaries not footnoted.

II

Caveats first, and they can be dealt with briefly. Greenblatt adds to the mystery by eschewing such footnotes and being, on occasion, intolerably vague when known facts might have helped him and us. For instance, we know Marlowe was baptised on February 26, 1564, two months to the day before Shakespeare (26 April), whose birth is popularly celebrated on 23 April, the day he died 52 years later. Three days for a baptism after birth in plague-infested times was about average and roughly the same could be advanced for Marlowe especially as an unfounded date of birth has been given out as 6 February for a century or more. Certainly “February” but Greenblatt makes no mention of this. He also doesn’t speculate as to the temper of Marlowe’s father James, litigious and quarrelsome as he seems to have been, judging from documents.

Greenblatt does though go into some detail about the fate of Marlowe’s family – themselves often barely literate, but known for acid tongues. More, he’s able to reconstruct a detailed account of Marlowe’s time at The King’s School, Canterbury: how he won a place there and how he proceeded to Cambridge. This is after opening with sometime roommate and dramatist Thomas Kyd’s torture and testimony which sets up the tensions of Marlowe’s “suddenness” and the murky aftermath of his death.

Above all Greenblatt is supremely readable. He balances scholarship, narrative flair, and the right amount of surprise and weave (he enjoys pouncing on anyone who doesn’t know what’s coming). In short, he has produced an engrossing yet popular biography of Marlowe.

What this murder mystery technique manages to establish is two parallel courses: the progress of Marlowe’s brilliance (featuring an unfolding imagination and daring) and the people on the way who hinder and occasionally help him. Thus Greenblatt cannily assembles a list of murder suspects, often devoting a chapter each to them. After “The Great Separation” which moves from Marlowe’s permanent removal from his family into a precarious schooling process – you could be thrown out of your golden opportunity, back into trade – into the curriculum. Canterbury had “fallen on hard times” since its heyday as a pilgrimage for Thomas à Becket. The sense of faded glory played over it. Greenblatt ably navigates the effects of Flemish immigrants and Kent’s perennial suspicion of invading foreigners. The volatility of the place is one ingredient; the school to which Marlowe proceeded in December 1578 is another. Yet however he proceeded to be “reputed a gentleman ever after” – a class automatically accorded to one who studied at university – Marlowe was never quite allowed to forget his origins.

Circumstantial yet acutely relevant detail is packed in, including the living conditions of schoolboy and scholar. Greenblatt convincingly argues that Marlowe’s “Greek” qualities as lyricist accorded to him by contemporaries were not idle convention. Marlowe had eagerly absorbed not only the Greek and Latin of the curriculum but as Greenblatt suggests, was allowed into headmaster John Gresshop’s famous library. All kinds of reading that Marlowe later used can be retrospectively extrapolated from accounts of Gresshop’s library. That particularly takes in the inspiration for far-flung geographies including the seeds of what was to become Tamburlaine the Great, Marlowe’s two-part theatrical debut. Alongside this is consideration of how educational theorist Roger Ascham wished to direct those boys who would become in time the rulers, pillars and explorers of an ambitious new nation. Renaissance humanism – despite Cambridge being a training for protestant priests – was pragmatically winning out over religious scholasticism.

III

Marlowe’s six years at Cambridge – from December 1580 – were protracted and slightly controversial. Greenblatt etches in the great shifts of Protestant orthodoxy shrouding recidivist Catholicism in some scholars, detailing the pitfalls awaiting the latter as “recusants” including horrific torture and death. Marlowe however gravitated bisected with the stirrings of scepticism. More familiar figures like Gabriel Harvey, Robert Greene and Thomas Nashe swim into view as do Canterbury contemporaries bound for the church or indeed recusancy and scepticism. Greenblatt reminds us that atheism no more tolerated than Catholicism. Even co-founder of Gonville and Caius College, Dr Caius, had his rooms broken into in 1572. His vast library was ransacked and confiscated.

Nevertheless, the university’s refusal to grant Marlowe his MA in May 1587 was met with a resounding slap-down from the Privy Council. This document, with five of the land’s grandest signatures, establish Marlowe’s good graces, and not, as Cambridge suspected, that he had gone to the infamous English priest’s training ground at Rheims. “It is not her majesty’s pleasure that anyone employed as he has been … touching the benefit of his country should be defamed by those that are ignorant in the affairs he went about.” Alongside this is an account of Marlowe’s brief return to Canterbury, and signing a legal document for one of his neighbours, this being the only trace of his writing that we have. Recruitment to Walsingham’s secret service, then as now, was something accomplished with a shadow of Greenblatt’s suggestions.

Detailing the life of agents allows Greenblatt to weave a more than plausible narrative over Marlowe’s recruitment and ultimately entrapment. Two of Walsingham’s agents stand out. Richard Baines who infiltrated Father Allen’s Rheims school yet was finally smoked out, would have in turn schooled Marlowe in all probability: in ways to avoid being detected. Though if Marlowe infiltrated Rheims his stay was far shorter than the undercover years Baines spent. Yet Greenblatt suggests Baines harboured some grudge or hatred of Marlowe too. Robert Poley, betrayer of the Babbington Plot to put Catholic Mary Queen of Scots on the throne, was another.

Greenblatt winds in both stimulators of Marlowe’s fortunes – like the circle around Durham House: Lord Strange’s abode and as theatrical patron, with privateer and major poet Sir Walter Raleigh, with scientists like Thomas Harriot lending a kind of wild permission to speak freely; and mixed with science, politics, or accounts of ill-fated colonies of the New World. This, Greenblatt asserts would have been the place to assert “Moses was a juggler” where nascent science was sweeping superstitions up. Another was the ninth Earl of Northumberland – Henry Percy, an enthusiastic and voracious intellectual, if not an original thinker.

IV

These are leavened with Marlowe’s introduction to theatrical life and accounts of his plays – Tamburlaine, reflecting his past reading and his buskined ambition. Passing more rapidly through The Jew of Malta and not for the moment treating of Marlowe’s best constructed tragedy Edward II, despite referring to its homoerotic content and clear dangers, Greenblatt concentrates on Doctor Faustus. Much of this seems to be speculatively linked with those free-thinking sessions around Durham House and Percy. It’s Percy’s and others’ studies of alchemy that furnish Greenblatt with the most detailed textual analysis, Doctor Faustus.

Greenblatt scores when he attends to the writing of the plays. His relating source materials first zoom in on Faustus’ steady rejections of other branches of study: you can see here how he relishes gathering all those threads of Marlowe’s early learning and point by point demolition. It suits Greenblatt too to place Faustus last since it accords with the psycho-biographical darkness he gathers towards Marlowe’s end. He’s good too on the “lame” revisions in the “B Text”, suggesting posthumous hands attempting to tame Marlowe’s dangerous creation.

Nevertheless, Greenblatt returns to Edward II, gathering both this “Extraordinary love” when treating of Marlowe’s sexual writing, and moving towards his unfinished long poem Hero and Leander. This seems to have been written in the country house of Thomas Walsingham, nephew of the spymaster. Greenblatt suggests that a false sense of security descended on Marlowe as he was entertained by those also escaping the plague that had among other things, closed the playhouses. Another there, also escaping from the plague, was a man hired as estate manager Ingram Frizer, a business agent. Another was Nicholas Skeres.

Greenblatt assesses his characters and evidence. Richard Baines reports Marlowe to the Privy Council. Citing other biographers like Park Honan he picks his way skilfully – and paying handsome tributes – through the theories surrounding Marlowe’s death. His conclusion carries a curious echo from the death of Mary Queen of Scots. It was more Marlowe’s atheism than anything else that marked him out, and Elizabeth wished him to be stopped. Greenblatt assess though that she did not mean assassinated.

Those who gave evidence at Marlowe’s death – the killer Frizer of course, fingered by Honan and long ago, Martin Seymour-Smith in 1972 as clearly intending assassination. Skeres too was present, as was agent Poley. It’s finely-argued and convincing, a strong synthesis of others’ research with added context for motive. Greenblatt’s introduction of Poley and Baines early into the narrative is only mildly speculative. That Marlowe would have met both is extremely likely.

V

Finally Greenblatt concludes, not with surprise that Marlowe should die at 29, but like Gibbon on the Roman empire, wonder that he subsisted so long. He continually emphasizes Marlowe’s dangerousness. “Marlowe was a genius but a profoundly disturbing one. His plays were themselves provocations. He said things that had never been said before, at least in public.” Above all Greenblatt contends that Marlowe made the English literary Renaissance, if not possible (there was Spenser and Sidney), then what it turned out to be. He brought it from the medieval world view “into the light”. His chief creation perhaps was the space that made Shakespeare possible. “Thanks to his astonishing style, the English language too a great leap forward … Shakespeare saw that he could now enter territory into which no-one before Marlowe had dared to enter. Shakespeare was the recipient of Marlowe’s gifts of reckless courage and genius.” What Greenblatt has managed too is to write a prequel to his own Will in the World. And he’s right. He has though proved Marlowe’s still neglected genius deserves more than honour or praise. His restless, dangerous transgressions demand to be read, re-read – and acted.