Cluj Theatre Festival 2025

Dana Rufolo in Cluj, Romania

19 October 2025

The Cluj Theatre Festival 2025, running from 9 to 12 October, is a recapitulation of productions shown at the Cluj National Theatre from 2020 until 2025 which, when viewed as a collection, revealed a preoccupation with destiny, both individual and collective. Hence, the theme of the Festival this year is “Destinies”. The destinies shown, in the four productions I saw (half of the total plays on offer), were not particularly wholesome, nothing like those happy ending situation comedies where everyone is flourishing. Rather, destiny is a grim and ghostly presence that deprives the characters on stage of their freewill.

In Adventures in Immediate Irreality (Întâmplări în irealitate imediată) Tudor Lucanu, the director, has converted the descriptions of a fevered imagination in the autobiographical novel of the same name by the Romanian author Max Blecher into a surreal swirl of images that destabilize and collapse one into the next. Blecher knew that he was destined to die prematurely; he lived until the age of 28 suffering from spinal tuberculosis. In 1936, when Blecher’s novel was published, the disease could not be cured. Nowadays there is a cure. Being alive for him at that time meant being hyper-conscious inside a body suffering from perpetual pain and fevers.

Alexandra Tarce, Matei Rotaru and Cecilia Lucanu-Donat in Adventures in Immediate Irreality.

Photo credit: Nicu Cherciu.

According to what he wrote, Blecher’s perceptions were filtered through both the pain he suffered and the consciousness that his body was betraying him. Under Lucanu’s direction, these perceptions include visual transformations – forms of hallucination – that destabilize and terrorize. A golden fish statue posed on a pillar for instance suddenly begins to whip through the air; a woman (Cecilia Lucanu-Donat) leans out of the radio set playing a violin; doctors (Matei Rotaru, Cosmin Stănilă, Alexandra Tarce) wearing rodent masks take charge of his body, pawing and poking, oohing and aahing over the temperature reading but never restoring his body to health. An oversized bovine carcass appears, nightmarish characters dance with it, the ill person is both a part of the action and observing. Blecher himself would have been placed in a full body cast as an attempt at a cure, and the carcass no doubt is a feverish reminder of his own rigid and unvital body.

At the conclusion, nestled in a chair, this character representing Blecher, played with suave concentration by Cosmin Stanila, can’t find a comfortable position which will sustain him long enough to be able to read the book in his hand. A marvelous mime, Stanila slips off the seat, squirming this way and that, but his body never gets comfortable, a perfect metaphor for the relentless capacity of the body to sabotage the mind.

Radu Dogaru, Cosmin Stanila and Matei Rotaru in Adventures in Immediate Irreality.

Photo credit: Nicu Cherciu.

Susan Sontag’s 1974 essay “Illness as Metaphor” discusses the irrationality of labeling disease as an expression of some weakness in the ill person’s personality, and although very few words are spoken in this staging, there are some lines referencing the Blecher character feeling culpable somehow for the affliction. But even this line of guilt is obliterated by the sounds and images that invade the surrealistic space that he inhabits. Performed in the Cluj National Theatre’s black box studio space called the Euphorion, which had been fitted out with bleachers on three sides surrounding the central performance space which is the floor of the room, the sounds of synthesized music, semi-articulated sounds, hysterical laughter, wild honky-tonk, and violin mingling with the fog and blue cloudy sky backdrop panels and surrealistic images including the staging of a shammed marriage bounced off the walls and resonated to the point of overwhelming our ears with blaring sounds, as if we too were to vicariously suffer from physical assault.

Lucanu is known for converting written texts into staged performances, and in Adventures in Immediate Unreality as in Demons, which he also directed and which played on the theatre’s main stage, his goal apparently is to successfully convert the written word into stage action rather than to reinterpret the conflict; he is careful to avoid bending the text to his will, as do Regietheater directors.

~~~

Demons. Stavrogin’s Confession (Demonii. Spovedania lui Stavroghin) is based on the 1871 novel by Fyodor Dostoevsky, which is also known in English translation as The Possessed or The Devils. It is presented to us in panorama style, with the action following the developments in the novel as honestly as possible. Again, Lucanu has avoided Regietheater.

The action revolves around the tortured individual Stavrogin who, according to Lucanu, is “tormented by existential questions” and yet is trapped, along with the other characters, in “the labyrinth of their own existence”. Played vigorously by the charismatic actor Ionuț Caras, Stavrogin is a compulsive sinner trapped in his cultural mindset that embraces Russian orthodoxy, but which cannot live by its principles. All around him, men and women slavishly respond to his inclinations, and although his intentions appear humanitarian, the results are murder, confusion, death, insanity and irrationality. The actress Sânziana Tarța plays both his mad wife and his potential lover with controlled exuberance, changing character with her costume and hairpiece so extremely that it is difficult to believe she is one and the same actress. It is a remarkably strong cast, with the actors setting themselves the challenge of credibility even though they are exaggerated personality types.

Sanziana Tarta, Matei Rotaru and Ionut Caras in Demons.

Photo credit: Nicu Cherciu.

This Demons calls to mind Vladamir Nabakov’s Lolita, also about depravity, but as dramatized the Dostoyevskyian characters are far denser, because they do not display a playful sense of irony but are, rather, intense and driven by a subterranean force. The great schism in all the characters between obedience and reckless loss of self-control is contained by an awe-inspiring scene design by Tudor Lucanu that sets the action against a backdrop of our globe and the weather in all its raging glory. There is nothing anthropomorphic that looks on; rather it is the earth itself, noble, solid, unperturbed, that establishes the quais-eternal kind of existence which is all that any creature on our planet can ever know. That the action is playing against a backdrop of eternity does not make the characters any less barbarous than they are, but it softens the impact of their heinous deeds so that the audience remains safe as observers; the actions on stage stay there – they are not contagious.

~~~

If only other countries in the world had the sense of self-reflection and self-criticism that Romanians have. Far fewer historically dreadful mistakes would be repeated, autocrats would be stopped dead in their tracks before they have done irreversible harm, and the body politic might therefore become more integrated and wiser. This self-reflective piece, directed by Ionuț Caras (who played the role of Stavrogin) and staged in the National Museum of Transylvanian History, is titled Nine Disgraces and other Scandalous Scenes from Romania’s Recent Past (9 RUŞINI și alte tablouri scandaloase din istoria recentă a României). Moments in Romanian history that are considered shameful have been staged. Each of the scenes was played with costume props that were taken from on-stage racks and with a backwall film projection. The actors performed on the bare hard museum floor; 12 excellent actors gave a semi-improvisational feel to the performance, increasing the impression of veracity.

9 Disgraces. (“Disgrace 8” with Adelin Tudorache).

Photo credit: Nicu Cherciu.

A partial list of the scenes includes the first episode where King Carol II abdicated the throne in September 1940 taking with him many riches including a part of the national treasure. There were episodes showing the Iași pogrom of June 1941; the communist deportation of peasants in 1951 to Bărăgan where they had nothing to live on and no housing so that their land could be collectivized; the capitalist exploitation and corruption that followed after 1989’s overturning of Nicolae Ceaușescu’s dictatorship; and other episodes that were a consequence of this corruption. The scene that resonated most with me was Episode Four: “The Decree Children”.

In 1966, Nicolae Ceaușescu declared that abortion was illegal because he wanted Romanians to have large families. The result was that over 100,000 children were born unwanted and handed over by their desperate parents to orphanages.

These children were seriously mistreated, but meanwhile propaganda films such as the one we saw projected onto the back wall portray happy singing children, the derisive aspect of this fake news revealed by the use of film footage that was either dull, as if faded by age, or else in negative black and white so that the children’s faces were dark and unrecognizable. Perhaps because I met one of these orphans, grown up, whose inability to control his impulsivity caused eternal sorrow to his adoptive family, I was not surprised to discover that the Romanian dictator filled the national coffers by selling these damaged children who had been deprived of personal love and care to unsuspecting couples in the West. It was the Western press that revealed the atrocities inside the orphanages.

~~~

“Thank you, Lord.” The one-woman show Twenty Years in Siberia (20 de ani în Siberia) is based on the famous diary of Anița Nandriș-Cudla, a Romanian peasant who survived the Russian gulag with her three sons in Siberia as a prisoner of Russians from 1941 until 1961. From Bucovina and extremely strong-willed, Anița managed to keep herself and her sons alive despite starvation, arctic temperatures and hard labour. She is very pious; she attributes her survival to the will of God, saying that He always was accompanying her.

This piousness comes straight from her diary, but it casts the performance – a dramatization of the diary – into something clichéd. Perhaps we have heard about the Soviet gulag too often? It is a fact, however, that Cudla’s diary is the first testimony and is considered among the very best. The actress playing the role of Cudla, Elena Ivanca, always with a shawl wrapped around her head and a penchant for elaborate religious iconography, keeps herself upright and dignified. She speaks at a slow pace indictive of steady perseverance and never loses herself in rage. She is pursued by a Russian commander, played by Sorin Misirianţu with a timidity and respect towards her that clashes with what his training has taught him -which is that she is slime, insignificant, less than a person. When eventually he gets up his courage to rape her, the conflict he experiences is so intense that he dies of a heart attack. But even this irony, and the sardonic humour in such a scene, is suppressed under the directorial decision of Sorin Misirianţu himself.

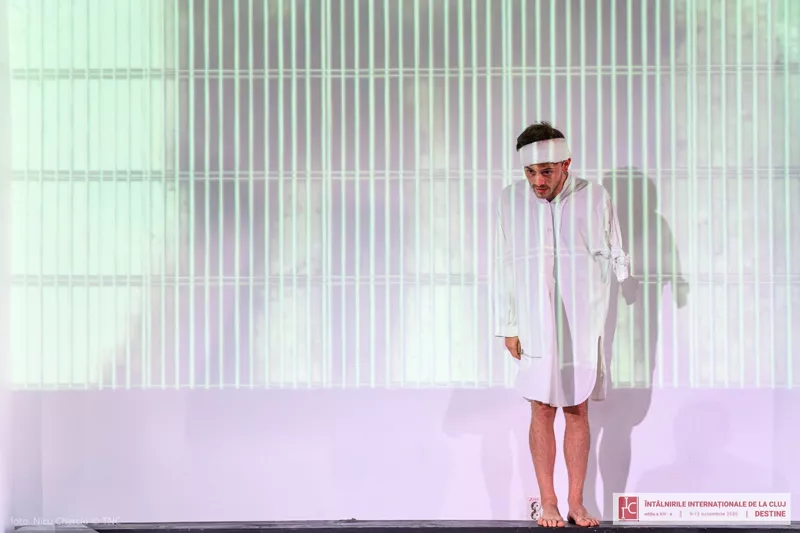

Sorin Misiriantu in 20 Years in Siberia.

Photo credit: Nicu Cherciu.

The difficulty with this staging of the diary is that is impossible to decide if we are being told that her belief in God was responsible for Cudla’s survival, or if indeed she was the victim of a destiny that could not daunt her because of her physical strength, determined personality, and clear-minded psychology. Indeed, the stage set in the Euphorion Studio theatre designed by Cristian Rusu included heaps of rocks and a back screen portraying raging winds and snow and harsh elements of nature, but she seemed to stand apart from these elements as if they could not touch her. In this production she was someone who might be deemed a saint.

A complement to the theatre productions, an exhibit devoted to 10 actors who were in repertoire at the Cluj National Theatre throughout their careers, was an added attraction to the festival. Entitled “Ten destinies fulfilled on the stage of the National Theatre”, the display devoted one panel to each actor, each panel showing press photos of every one of their performances in the National Theatre of Cluj over the years. This display was the most positive use of “destiny” that I saw. The productions themselves strongly reminded its audiences that Romanian suffering in its recent past history of repression and domination is deeply inhumane and must never be normalized.

Photo as thumbnail and as leader to this article shows Elena Ivanca in 20 Years in Siberia. Photo credit: Nicu Cherciu.