“The Harder They Come” at Theatre Royal Stratford East

Neil Dowden in East London

28 September 2025

★★★★

Perry Henzell’s 1972 film The Harder They Come was a cultural landmark. It was the first Jamaican feature film, which “brought reggae to the world” as well as making an international star of its lead Jimmy Cliff who also wrote several songs for the terrific soundtrack. Very loosely based on the real Jamaican outlaw Rhyging, but with an added musical element, it follows the exploits of aspiring reggae singer-songwriter Ivan as he turns to crime after his hopes are cruelly punctured.

Photo credit: Danny Kaan.

This stage musical, which premiered in New York in 2023 with a book and three new songs by Pulitzer and Tony Prize-winning playwright Suzan-Lori Parks, now arrives in the UK in a new production directed by Matthew Xia. It is not the first time Theatre Royal Stratford East has hosted a musical adaptation of The Harder They Come: they had a big hit with an earlier version created by Henzell himself in 2006 which transferred to the West End, and was revived the following year. But Parks’s version is very different – and deserves to be as successful.

This show is not only much less gritty and violent than the film – perhaps inevitable with a musical – but it more explicitly touches on social injustice while also having a more positive message captured in the Cliff song title “You Can Get It If You Really Want”. Ivan is portrayed more sympathetically as a naïve young man from the country who comes to Kingston dreaming of becoming a pop star but is mired in the corruption of the city.

Compared with Henzell’s approach on screen and stage, Parks’s Ivan is not just an immature person who confuses fantasy with reality in his bid to become famous and goes violently off the rails, but someone who stands up for his – and others’ – rights. Here he is not merely an antihero, but the voice of oppressed people as he rebels against the establishment represented by a predatory minister, an exploitative music mogul, a threatening drug-gang leader, and venal police.

Ivan is far less trigger-happy here – he kills only one person, a policeman who fires on him first as he tries to arrest him, so it is almost self-defence. Also he is not unfaithful to his girlfriend Elsa; and although she breaks from him after she learns what he has done, her heart remains faithful and she refuses to betray him to the police. She and Ivan’s religious mother Daisy are given more significant roles, adding an emotional layer and representing the moral heart of the story.

There is an irresistible pulsating energy in Xia’s thrillingly inventive staging. The opening gives a vibrant impression of chaotic street life in Kingston (cue Toots and the Maytals’ “Funky Kingston”) as the distracted Ivan arrives and is promptly conned out of his possessions. The hustling of the rude boys is contrasted with the spirituality of church-goers, but even they are revealed to have carnal thoughts during the gospel number “Let’s Come in the House” when in an audacious set piece they disrobe midway to bump and grind in their imaginations. The dancehall scene where Ivan seizes his chance to perform to a growing fan base is also brilliantly done (with Parks’s stirring song “The Time Is Now”).

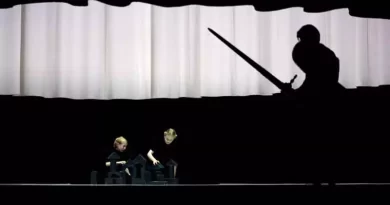

Photo credit: Danny Kaan.

There is deft use of a descending white curtain to represent the screen where the spaghetti western Django is projected that inspires Ivan to dress as a cowboy and brandish a pistol in each hand (accompanied by Parks’s sadly ironic “Heroes Don’t Never Die”). As Ivan’s ambitions lead him into trouble and he goes on the run, his notoriety is broadcast by a reporter in news bulletins on a TV screen.

Simon Kenny’s two-tiered design of a crowded ghetto with buildings made of corrugated iron, breeze blocks, and dilapidated timber jumbled together, connected by rickety staircases, is impressive, while Jessica Cabassa’s authentic costumes evoke the period superbly. Ciarán Cunningham’s multi-coloured lighting (including Rastafarian green, gold, and red – though Ivan is not actually a Rasta) is used to good dramatic effect, and Nicola T. Chang successfully creates a soundscape for Kingston.

Shelley Maxwell’s dynamic choreography relays the restlessness of the city as well as accompanying ensemble songs. An out-of-sight six-piece band led by music director Ashton Moore keep an infectious beat with ska, rock steady, and reggae numbers also including Desmond Dekker’s “007 (Shanty Town)”, the Melodians’ “Rivers of Babylon”, Johnny Nash’s “I Can See Clearly”, and Cliff’s “Many Rivers to Cross”.

Natey Jones (who also starred in the original New York production) is a charismatic Ivan for whom we are rooting even when he starts making bad choices through frustration, and he nails his big songs with full-throated passion. His intimate love scenes with Madeline Charlemagne’s Elsa (who breaks out from her tightly controlled upbringing) are touching – she also boasts an impressive singing voice.

There are entertaining performances from Jason Pennycooke as the hypocritical Preacher who abuses his role as her guardian, Thomas Vernal as the powerful record producer Hilton who rips off his artists, and Danny Bailey as the ganja king José whose relaxed bonhomie conceals a businessman’s ruthlessness. And Josie Benson adds gentle poignancy as Daisy who tries to persuade her son to return to the countryside but is powerless to stop him from succumbing to the city’s sleazy allure.