“The Weir”, Harold Pinter Theatre

Jeremy Malies in the West End

22 September 2025

★★★

You need to be a good and precocious observer to write a script like The Weir at the age of 25, and Conor McPherson’s gentle dismantling of his characters’ self-delusions on the north-west coast of Ireland remains compelling.

Seán McGinley as Jim.

Photo credit Rich Gilligan.

A car mechanic, an odd job man, and a pushy property developer are drinking bottled stout (the tap for draught has given up) with whiskey chasers. The owner of the tatty pub is an integral part of the conversation and tonight there is a “blow-in”, this being the local term for a stranger. The newcomer is a bereaved woman from Dublin whose marriage has foundered after the loss of a child. The men speak of her relocation from Dublin as though she has come from another galaxy.

Has Conor McPherson’s play aged well since 1997? Changes in pub and leisure culture (as well as good but dated gags about everything from racehorses to chip shops) mean that this is increasingly a period piece. No pub-goer these days would spend more than ten minutes without looking at their smartphone and that probably rules out lengthy storytelling. But the play’s themes of addiction, bachelorhood, and Beckettian self-reproach at spurned opportunities are primal. And while stories of moonshine-fuelled gravedigging sessions might be quintessentially Irish, the details of fairy folk, ley lines, and phantom children are suspense-laden in a way that cuts across most cultures and explains the play’s international success.

Mark Henderson’s lighting artfully brings the decrepit nature of the place to our attention, and his design also emphasizes depth with a standard lamp at the very back of Rae Smith’s set which is full of closely observed period items such as snacks and now discontinued bottled beers. When necessary, Smith’s configuration allows our attention to be directed down a corridor to the exit and the shingle cove outside that leads to the Atlantic. A peat-burning stove issues smoke but no fumes.

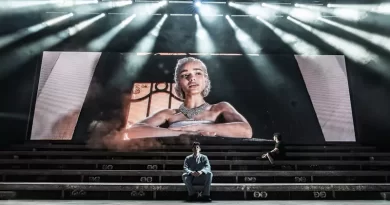

Seán McGinley and Owen McDonnell.

Photo credit Rich Gilligan.

Directing his own play for the first time, McPherson benefits from the monumental (and much hyped in pre-publicity) presence of Brendan Gleeson as Jack. He is 20 years older than the part as written but you see why McPherson and the producers wanted him. Gleeson (star of Martin McDonagh’s films The Banshees of Inisherin and In Bruges) immediately establishes a backstory for his character. Crucially, he produces the purest phase of the evening for his monologue during which everybody in the theatre has a dizzying trip based on pure relish for elegiac turn of phrase and Hiberno-English.

Jack’s is the only story among the set pieces that does not take a metaphysical turn, but he speaks of aching regret after watching a fiancée who wanted to be with him eventually marry another man after he (Jack) lost interest for a while. I came to attention at Gleeson’s keening, “There’s not one morning I don’t wake up with her name in the room.” Jack’s garage has been bypassed by the main road to Carrick and his whole life is now bypassed.

Playing outlier Valerie, Kate Phillips nails her own big set speech while being inventive physically as she shows her character fending off the attentions of loathsome would-be adulterer and real estate shyster Finbar played by Tom Vaughan-Lawlor. Hers is a drama school audition piece now and quite familiar but it’s fresh and seemingly spontaneous here. You reckon that on what are sure to be subsequent trips to the pub, Valerie will make the regulars more open and emotionally articulate.

Seán McGinley’s character Jim talks as if in a stream of consciousness about sinister jabbering old women, dead birds, and untenanted graves. McPherson may well want us to think of Hitchcock films. McGinley reappears from The Brightening Air which premiered at the Old Vic this April, also under McPherson’s direction. Development from disgraceful fake American-style evangelist to warm-hearted barfly will please fans of this prodigiously gifted and personable actor.

And the title? This is only a guess, but we know that a weir has been built in the Fifties during the working lifetimes of the characters’ fathers. A weir is constructed as an obstacle to the passage of water, so maybe McPherson is equating pent-up flood water with stifled emotional lives? Occasionally a weir gets a free discharge into open water. The advent of Valerie (damaged and pent-up herself of course) may be just such a channel for two decent and engaging men.

This is pure McPherson. His The Veil from 2011 also deals with hauntings, and The Weir has a similar barroom setting to that in The Brightening Air where the period is the Eighties. But I found the delivery of the stories to be mixed in quality and was not always sure that (for what in the stalls was a restless and flat audience on press night) they always found their mark. Gleeson as talisman anchors the evening as his character forms what might be the beginning of a bond with Valerie. There is a Chekhovian stoicism – possibly even mild optimism or salvation – at the end. And perhaps McPherson has absorbed a lesson from American essayist and journalist Joan Didion? We tell ourselves stories in order to live.