“Love, Love, Love” at Lyric Hammersmith

Neil Dowden in west London

1 June 2020

Mike Bartlett’s 2012 play Love, Love, Love is a wickedly entertaining comedy-drama that sets baby-boomer parents against their Generation X children. Over a period of 45 years, we follow a family whose fortunes are inextricably linked to evolving cultural values and socio-economic changes. lt’s a savage satire of modern mores that, especially early on, is very funny but that ultimately becomes much darker as the price of the fun becomes apparent. The three acts set in 1967, 1990 and 2011 show pivotal moments in both personal and national development.

We start in the “summer of love” of 1967. It is the night of Our World, the first live, international, satellite TV production featuring creative artists in a show of cosmopolitan harmony, with a global audience of up to seven hundred million. As the strains of “Love, love, love” from The Beatles’ debut performance of “All You Need ls Love” die away, Sandra and Kenneth meet for the first time in the London flat of his older brother Henry. This is supposed to be the first date between the conventional Henry (whose nine-to-five life is much closer to their working-class parents’ than the hippies of the swinging sixties) and Sandra. But Sandra and Kenneth find they are kindred spirits. Both are Oxford University students: she is a pot-smoking “posh bird” who has a temp job at a trendy clothes boutique, while he is upwardly mobile but prefers a hedonistic lifestyle to studying. As they get it on, they look forward with optimism to a new age of freedom — and free love.

We next see them in 1990: on the day of the Poll Tax Riots, near the end of the Thatcher era. The middle-aged Sandra — now a high-flying, shoulder-padded business executive — and Kenneth are married and living in suburban Reading with their teenage daughter and son, Rose and Jamie. But they are far from attaining domestic bliss. lt is supposed to be a celebration of their daughter Rose’s sixteenth birthday, but as Sandra and Kenneth get pissed their bickering becomes increasingly bitter, to the embarrassment of their alienated, neglected children who also squabble with each other. Sandra cuttingly tells the sensitive Rose, “You’re pretty when you make the effort”. It emerges that both she and Kenneth are having secret affairs as the marriage heads for the rocks.

Finally, we move to 2011, at the start of austerity. The divided family gather together on the day of Henry’s funeral, at Kenneth’s luxurious house where he has retired to play golf. We see the true cost of the now divorced Sandra and Kenneth’s irresponsible self-absorption in the shape of their damaged children. Jamie is an agoraphobic living with his dad and losing himself in a virtual world of video games. The thirty-seven-year-old Rose, struggling in a precarious economic environment, demands that her parents buy her a house to get her on the property ladder. They reject her request. She delivers her verdict on not just them but her parents’ generation: “You didn’t change the world, you bought it and then privatized it.” At the end, Sandra and Kenneth toy with the idea of spending their money — and their children’s inheritance — by travelling on a world cruise together.

As usual, in Love, Love, Love, Bartlett cleverly mingles the personal and the political in a state-of-the-nation play in the guise of a family drama. As a signifier of their lack of unity, this family is given no surname that binds them together. The play investigates intergenerational conflict, social class, lost idealism, parental responsibility, and blame culture. But this is no black-and-white polemic, with Bartlett brilliantly making our sympathies switch between the self-centred, fun-loving parents and the dependent, miserable children.

Sadly, this first major revival was cut short after only a handful of performances by the coronavirus lockdown, with the press night taking place in a more than half-empty theatre. lt’s a shame since Rachel O’Riordan’s second production since becoming artistic director of Lyric Hammersmith was sure to have been a popular hit. For each act, Joanna Scotcher’s set and costume designs beautifully evoke the changing fashions of the age.

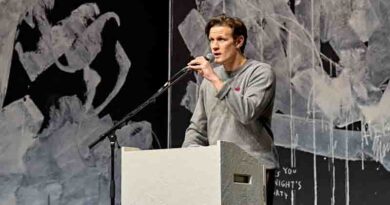

With the help of wigs as well as clothing, the cast do well to suggest the characters’ ageing. Rachael Stirling gives a thoroughly entertaining if slightly over-the-top performance as the monstrous Sandra whose patronizing put-downs are acidly amusing. Nicholas Burns’s Kenneth is more laid-back and amiable, but equally selfish in his pursuit of pleasure. Isabella Laughland conveys Rose’s lack of self-esteem and sharp sense of injustice, while Mike Noble shows how the immature Jamie declines into mental illness. And Patrick Knowles plays the hard-working “square” Henry, left behind by the younger generation who believe they can have whatever they want.