“Rhinoceros” at Almeida Theatre

Jeremy Malies in North London

5 April 2025

Is it an act of hubris (or worse) to both translate and then direct Eugène Ionesco’s 1959 play Rhinoceros? Surely the storyline applauds the one character (Ṣopẹ́ Dìrísù as Bérenger) who will not submit to a top-down power grab and conformity so there is unwanted irony?

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

Translator-director Omar Elerian may well have used a highly collaborative even devised rehearsal process. Nobody outside the company will know. So, this could all be part of the joke in a playful self-aware version. It would be logical that a satire on totalitarianism has creative power residing predominantly in the hands of one person.

As we take our seats, a radio news bulletin in French is playing from a wireless on the clinical white set designed by Ana Inés Jabares-Pita. The bulletin is describing uproar in a provincial town but in a non-specific way.

The hero Bérenger is soon being upbraided by superiors at his office for mild alcoholism and lack of self-discipline. These pep talks continue, but our attention is focused on the fact that (bizarrely for France) a rhinoceros has been sighted in town.

Surely a rhinoceros is not indigenous and, out of interest, did the specimen that ran through the square have one horn or two? As more and more people either become a rhinoceros or report sightings, it would be so easy for Elerian to make unsubtle references to Trump supporters, Erdoğan loyalists, or (right up to the minute) Marine Le Pen since we are in France. Instead, there is a single reference to a “rhinoceritis” movement and discussion of how rule-abiding we were during Covid. With Berenger (for me at least) very much like Winston in Nineteen Eighty-Four it’s as if the rhinos are whatever we dread as the worst kind of fascist or ideological contagion.

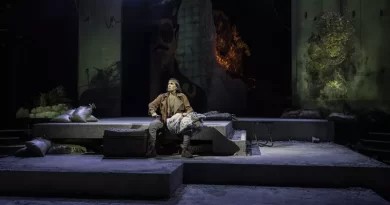

Ṣopẹ́ Dìrísù as Bérenger.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

I have no idea why Elerian leaves many points about the rhinos being green in his translation when this is Ionesco’s specific reference to uniforms worn by the Wehrmacht. The green is emphasized by Robin Fisher’s occasional close-up live video projection but unless I’m missing something, the colour is meaningless in this treatment other than being a sickly bilious shade that lighting designer Jackie Shemesh emphasizes elsewhere with use of filters.

Much of this is anchored on a metatheatrical, slightly Brechtian (sound effects being produced live on stage are all of a piece) master of ceremonies figure played by Paul Hunter of the company Told by an Idiot. His regular collaborator Hayley Carmichael plays a character who has had a particularly close encounter with a rhino. She conveys all this with sustained clowning that came nowhere near amusing me.

Hunter is far funnier and more inventive as he places his announcer figure somewhere between Max Miller and Ken Dodd, right down to the latter’s wild hair. He is forever pulling the rug from under the main narrative with asides. Hunter begins well by leading us in hand gesture games. But even his considerable comedic abilities are stretched, for me at least, by the time he is orchestrating audience members as they play kazoos. One woman in the front row is railroaded into playing her kazoo solo. Did she really want to be part of this? Is it late in the year for panto? And yet, later on, I wondered if asking the audience to behave foolishly by playing kazoos is Elerian’s way of showing how easy it would be to make us sing a fascist anthem or make a salute.

And the play itself is stretched from three to four acts, mainly to accommodate Hunter’s interactions with the audience and his running critique of the plot which often involves reading Ionesco’s stage directions aloud and mocking them. Amusing additions include an extract from a Kenneth Tynan essay on Ionesco and Gary Lineker opining about the plot. There are hints early on that the rhinos may simply be fake news.

Mad hair runs across many cast members and serves to hint at rhino horns. Jabares-Pita, who has also designed the costumes, has most of the cast showing conformity in white lab coats except for Bérenger who must be the outlier in every sense. Dìrísù impresses with the way he gradually reveals the character’s enormous strength of will.

The show is something of an endurance test at two hours 40 minutes. The sound design by Elena Peña has cast members making noises themselves in the manner of Foley artists though strictly speaking the Foley approach is used to enhance sounds after filming.

Elerian also translated and directed Ionesco’s The Chairs at the Almeida in a production that underwhelmed my colleague. Anoushka Lucas as Daisy, Bérenger’s romantic interest, sings an Italian love ballad to wonderful effect. Musical director John Biddle also has several roles and plays jazz-infused Bach onstage.

At least Ionesco’s text is a warning not a prediction. If there is a stampede at the box office for this, I won’t be part of it and would see it as coerced herd mentality. That may of course be the point with the joke being on us. All of this has dawned on me many hours later. What I know for sure is that I would not have the courage of Bérenger.