Venice Biennale 2021: Maggie Rose

Maggie Rose in Venice

1 August 2021

I was very fortunate to attend nearly all the shows at this year’s forty-ninth Venice Theatre Biennale (2-11 July 2021), which were the works of companies from Italy, Poland, Holland, Hungary, Spain, and the UK. At the opening Golden Lion award ceremony – given to Krzysztof Warlikowski who is artistic director of the Nuovy Theater in Warsaw – unfolding as it did in the aftermath of the second lockdown, there was a definite buzz of excitement and enthusiasm as artists, theatregoers, and critics got together face to face.

Hard to be a God by Proton Theatre. Photo credit: Andrea Avezzù.

Ricci/forte honoured the Polish director Warlikowski for “offering us a vision of society threatened by radical change and increasingly under siege by a tentacular ruling class of ravenous predators, highlighting the violence in social and family relations and the urgent need that the emotion of a pure and simple desire to love can give us” In keeping with the idea of excellence advanced by the Biennale’s artistic directors, this year’s shows reflected on the troubled times we are living in without explicitly dealing with the impact of the pandemic on our everyday lives. Groups like Barcelona’s Agrupación Señor Serrano, Proton Theatre in Budapest, and Italian director and curator Filippo Andreatta’s OHT (Office for a Human Theatre) made ample use of video projections and work stations to the end of combining live theatre with new and fast-changing technologies. Other groups relied much more on the actor positioned in real time and space. Some chose the one-person play, perhaps prompted by a wish to return to the very basics of live performance – which is, as Belgian playwright Maurice Maeterlinck suggested long ago, a single actor telling a story which puts the actor and the audience in touch with hidden powers in the universe.

The Mountain, the show the Spanish Agrupación Señor Serrano brought to Venice, explored how impossible it is to access truth in our contemporary society dominated by the media. Given the often discordant media coverage concerning the origins and nature of Covid19 and the spread of the pandemic, the heated controversy around the different Covid19 vaccines, The Mountain resonated loudly. Thanks to a continual juxtaposition of live performance and virtual reality, through video projections on screens of various sizes together with two workstations where small-scale models are being made and simultaneously projected onto the screens, audience members are invited to perceive reality as realities: multiple and relative. Importantly, though, the three dramatists and directors, Àlex Serrano, Pau Palacios, and Ferran Dordal, began the show with live onstage action: a young woman, dressed in male sports attire, is playing badminton while teasingly inviting us to reflect on why we can’t call the game she is playing “baseball”. After all, she maintains, if we come to a consensus, even among a few people, we can change the game’s name. In our Post[1]Truth culture, she prompted us to consider the question: where exactly does truth reside?

The Mountain. Photo courtesy of Venice Theatre Biennale.

This fast-paced show also focuses on a string of real-life events which are linked to the main theme. We watch television clips of bloodstained, stands yelling and inviting spectators to enter the playing space and take their seats. He turns out to be a character called the Doctor, visiting from another planet to observe what is happening on earth. The action unfolds “onstage” on the truck facing the audience and on a video screen, showing streamed action on the truck to the left of the stage. The story, written by Mundruczó and Yvette Biro, is one of violence and exploitation in a context where barbaric actions go unpunished – the setting and lack of morality clearly allude to the eponymous 2013 science fiction art film by Russian director Aleksey German. Three young women have been trafficked from Hungary to Western Europe; by day they work in a tailoring workshop (realistically reproduced on the truck) sewing jeans for Gucci, and at night they work as prostitutes.

As spectators, our focus continually shifts between the onstage action and the video projections to our left. Onstage the girls and Mammy Blue, the manager of the workshop and the brothel Madame, discuss the difficult life they lead. At one point, an abortion is carried out, the perpetrator, heavy-handedly using an umbrella spoke that has been disinfected with some cleaning liquid. Mammy Blue remarks, “We’ve not got enough money for pills” to explain the unwanted pregnancy. On the screen are violent episodes reminiscent of Pulp Fiction, including one where a girl is abused by her pimp; he beats her to the point where her back bleeds. The mood of the play continually and abruptly swings as the girls sing love songs such as the famous 1970s lyric, “What the world needs now is love, sweet love” – an ironic counterpoint to the world they find themselves in. I felt angry that the suffering and oppression we witness in Hard to Be a God is still going on –and also ashamed that we in Western Europe have done little to put an end to trafficking.

Kae Tempest. Photo credit: Cat Bauer.

In recent years Thomas Ostermeier, artistic director of Berlin’s Schaubühne, has been engaged in a style of political theatre which seeks to give voice to people on the margins. His 2018 production Histoire de la Violence by acclaimed novelist, dramatist, and activist Édouard Louis made his political engagement blatantly clear. This year Ostermeier continues the collaboration with Louis, directing Qui a tué mon père (Who Killed my Father) On this occasion, Louis not only wrote the piece but also performs in what is a one-person show. The action opens on Louis, a tall, slender young man, alone on a stage that is empty except for a video projection of a moving road. Sitting and speaking into a microphone, the young man relates the story of his relationship with his abusive, working-class father. Initially, when he was a child, his father was unable to accept his homosexuality. Then suddenly the young man moves to centre stage to show how he rebelled. He dons a wig and a dress, and his body springs to life as he sings and dances, expressing euphoria in this act of crossdressing. His liberation is part of a journey which both father and son undertake, symbolized by the image of the moving road. The father comes to understand his homosexual son and is proud of his achievements as a writer, while the son comprehends how his father has been brutalized by the social system he lives in.

The play’s scope, though, extends way beyond Louis’s coming-of-age story. We watch astonished as the young man boldly pins photos of the most recent French presidents –including Jacques Chirac, Nicolas Sarkozy, François Hollande, and Emmanuel Macron – onto a clothesline. He denounces each of these politicians for having made life persistently harder for the poor and especially for those people who are living on credit. At the end, there’s a call for action that unexpectedly comes from the father; he tells his son, “We need a real revolution”.

Qui a tué mon père written and performed by Édouard Louis.

Photo credit: Jean Louis Fernandez.

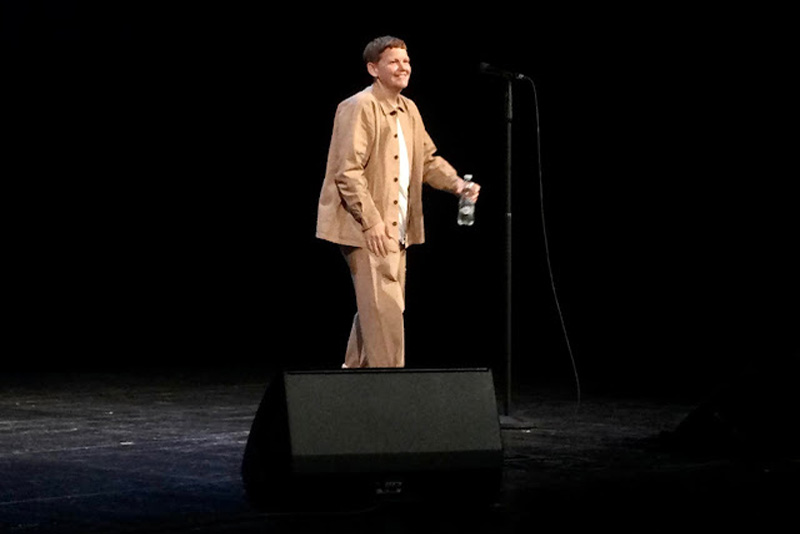

Kae Tempest was the recipient of the Biennale Silver Lion for Theatre 2021, given to her because this poet is “the most powerful and innovative poetic voice to come out of Spoken Word Poetry in recent years”. Tempest brought The Book of Traps and Lessons (previously released as an album in 2019) to the festival; like Qui a tué mon père, it offers a compelling critique of contemporary society. On an empty stage, dressed in a nondescript beige trouser suit, this author-performer delivered what might be a biographical story that moved swiftly between the deftly honed memories of an intimate relationship and a broader social commentary as the narrator walks through London. In the present work, the explosive, youthful energy of previous shows such as Circles or the political anger of Europe is Lost (written and performed by Kae when she was still Kate Tempest; in 2020 the female artist Kate morphed into Kae, announcing their identity as a non-binary person.) have largely given way to a heart-wrenching search into the performer’s identity, if not also into the soul of a nation that is ill and traumatized by Brexit. The traps of love emerge crystal-clear in the imagery of this 45- minute monologue which was delivered with such sincerity and passion that it stayed with me long after the performance was over.

“‘I trap you so much!’/ I should have whispered in your ear as we fell asleep/ Bodies unbound /Sheets soaked / Hearts hammering.” Kae Tempest’s performance received a standing ovation from the ecstatic audience at the Biennale’s Piccolo Teatro Goldoni. Tempest was recently seen in London at the National Theatre with Paradise, her rewrite of Sophocles’ Philoctetes which she calls a “contemporary morality play”.