“The Seagull“, Deutsches Theater

Hans-Jürgen Bartsch in Berlin

18th April 2023

Chekhov’s dramatic work features regularly in the repertoire of Berlin’s theatres, particularly the classics such as The Seagull, Uncle Vanya, Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard. I cannot remember a season in which a Chekhov play did not feature at one of the public or private Berlin theatres. Some successful productions – like Three Sisters at the Maxim Gorki Theater (directed by Thomas Langhoff in 1979) and the Schaubühne (directed by Peter Stein in 1984) – will be remembered for their longevity; they were performed in rotation for several years. Another kind of record was broken in 2011 when altogether three revivals of The Cherry Orchard were on show at the same time (at the Berliner Ensemble, Deutsches Theater, and Sophiensäle). Currently, Die Möwe (The Seagull) is playing at the Schaubühne and at Deutsches Theater.

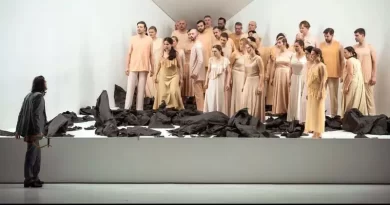

The ensemble.

Photo credit: Matthias Horn.

The one that opened at Deutsches Theater on 7 April is a revival unlike any other. Announced as a Wiederaufnahme (resumption), it is a faithful replication of the legendary production which Jürgen Gosch directed at this venue in 2008. With two exceptions, the cast is the same – only fifteen years older. The set, a simple anthracite-coloured box, is the same. The only furniture is a long, also black, bench at the rear from where the actors who are not “on” watch their colleagues’ performance while awaiting their turn. There is no Russian paraphernalia, not even the customary samovar in the stage design by Johannes Schütz.

At curtain call, only the director was missing. Gosch had died of cancer in 2009, half a year after the premiere of his celebrated production. He lived just long enough to see his Seagull rewarded with an invitation to the annual Theatertreffen festival as one of the ten “most remarkable” German-language productions of the 2008/09 season. And the theatre magazine Theater heute selected it as the “play of the year”.

The opening scene starts with a coup de théâtre : two of the Treplov estate’s labourers, acting as stagehands, heave in a boulder onto which Nina (Kathleen Morgeneyer) climbs to deliver the lines Kostya has written for her. She does not merely declaim them; she acts them out, parodying the creatures from Kostya’s strange Weltschmerz drama: a lion, partridges, stags, fish – a stupendous turn of comic acting. Fumes rise from sulphur bowls, and Lucifer’s eyes, two bicycle rear lights dangling from fishing rods and swung over the scene by stagehands, glow in the dusk – theatrical dilettantism expertly done.

This Seagull, utterly captivating throughout the three hours it lasts, is like no other I’ve seen. Gosch’s trenchant observation sheds a new light on the predicaments of the unhappy people gathering every summer on Arkadina’s estate. Here too they suffer from the tedium of country life and from the (unrequited) love they invest in the wrong persons: the self-appointed avant-garde writer Kostya in the aspiring actress Nina, the estate manager’s daughter Masha in Kostya, Nina in the successful, but emotionally shallow writer Trigorin, the manager’s unhappy wife Polina in Dr. Dorn. But their real affliction, which Gosch’s reading makes patently apparent and which permeates all performances, is nervous, almost panicky anxiety: the fear of getting old and ending an unfulfilled life. As Arkadina’s brother Sorin remarks in Angela Schanelec’s crisp new translation: ‘My life has passed, but without me’.

All this is brilliantly demonstrated without sentimentality, in almost laconic fashion, by a superlative ensemble. In her common flowery dress and flat shoes, Corinna Harfouch’s Arkadina is not the eccentric selfish diva as she is normally portrayed, but a practical middle-aged woman and mother, worried about her age, her finances and her son’s future. She does use her theatrical skills when the situation requires – as in the dramatic scene where her lover threatens to leave her – but even in such flare-ups she remains in control of her emotions. Quite evidently it is habit rather than passion that ties her to the much younger Trigorin (Alexander Khuon), a compulsive and very popular writer whose aloofness and lack of sensitivity not only prevent him from being a good one as well, but also cause him to destroy Nina in the end. Angling appears to be his only real passion.

Jirka Zett, tense and humourless, gives an effete insecure Kostya. Even his feelings for Nina suggest a limpness. Christian Grashof as Arkadina’ brother Sorin is marvellous as the constantly moaning hypochondriac, using his infirmity to solicit the others’ sympathy. There is impressive support from Meike Droste as the downhearted Masha, Christoph Franken, her unattractive, sweaty teacher husband, Bernd Stempel as Shamrayev, the prattling manager of the estate, and Simone Zglinicki as Shamrayev’s wife Polina, an elderly cry-baby who is tired of her boorish husband and yearning for the affection of Dr. Dorn (Peter Pagel).

All characters are drawn with great precision. Every speech rings true, every gesture looks right. And following Chekhov’s advice that the play should be read as a comedy, this Seagull abounds with many wonderfully funny scenes – in line with Samuel Beckett’s belief (in Endgame) that nothing is funnier than people’s misfortune.

.

~