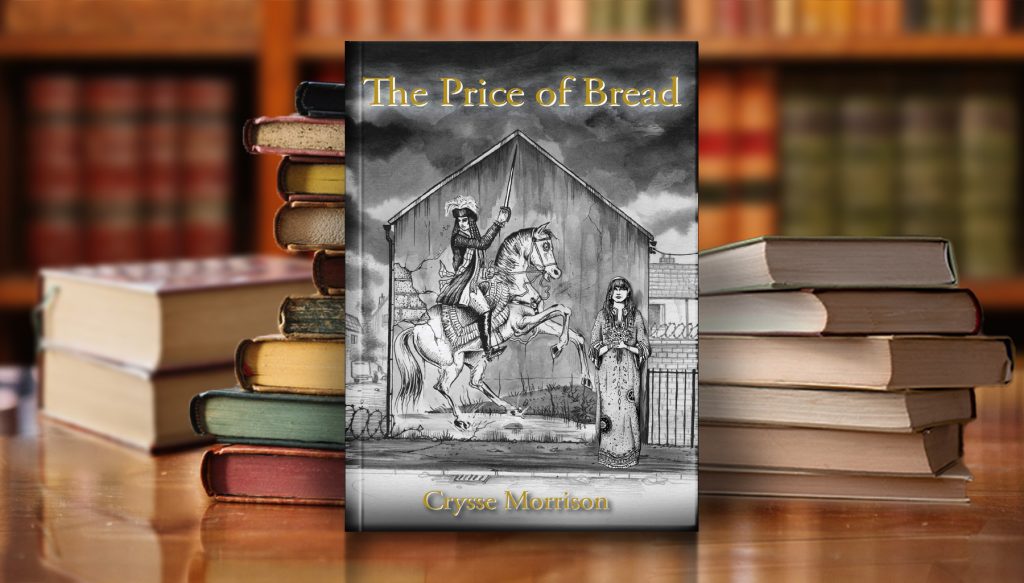

“The Price of Bread”: Crysse Morrison

The Price of Bread by Crysse Morrison

Book review by Dana Rufolo

1 September 2020

The novel The Price of Bread by Crysse Morrison, published in July this year by Hobnob Press, is extraordinary. It is a vivacious and introspective study of a clan – indeed, an extended family – of young adults, mostly students, living in poverty in Belfast in 1970. It is a fast-moving story that has balanced narrative and history, the private and the public, with sensitivity. Reading it non-stop, I soon became convinced it is a potential Booker Prize candidate.

ln The Price of Bread, we immediately sink into a private sphere that encapsulates hippie-style idealism, embraced especially by the protagonist Lee (living her conviction that “all you need is love”) whose peers are her entire world. It is chock-a-block packed with young wedded couples, lecturers, babysitters, coffee, wine, women friends, babies, toddlers, unheated cold water apartments, parties, and youthful sexual passion. And, importantly, Ludwig Wittgenstein who is quoted as saying that all thought depends on language. (“The limits of my language means the limits of my world”).

That is the melody. But there is also a background rumbling, which is the inception of “The Troubles”. Received attitudes of intolerance and xenophobia mingle with threats like “We’ll firebomb you”; the city fills up with “dangerously dark” alleys, bitter Catholic versus Protestant conflicts, hate-promoting songs of tribal loyalty, tear gas bombardments, child abuse, rising bread prices, and signs of British imperialism.

Lee is a heroine, and she never turns cynical when words aren’t invented quickly enough to define and sustain the radical idea of community she dreams of which is utterly at odds with her surroundings. Ultimately, Lee has to leave Northern Ireland and moves back to England with her with her two small sons, but she does not surrender her belief that love is still potentially more powerful than hatred, as this passage from the book indicates: “Lee feared that she was close to losing something precious in her life: the ideal she had lived by seemed to be disintegrating. All around them, tribal bonds and clan divisions had created hate, violence, assault and death, and they had held out for something else. Love, not the christ-god that both sides had erected on a burning cross, but palpable, visceral, ongoing daily love. Connection at its most intimate and honest, and vulnerable. If that’s eliminated, the world goes insane.” (p. 155).

Sanity is the greatest value, and clear mindedness is preserved for Lee by disassociating from the city of Belfast’s poisonous environment. Rarely have I read a book that casts such an accurate look at the ’60s – an era of free love impossible to imagine nowadays – in the context of hostile social forces.