“The Maids”, Jermyn Street Theatre

Jeremy Malies in the West End

14 January 2024

Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Jean Genet were all influenced by the 1933 murder in Le Mans of a socialite and her daughter by two sisters working for the family as live-in-maids. In what was widely interpreted as class envy, the women simply bludgeoned their victims to death.

Charlie Oscar and Anna Popplewell.

Photo credit: Steve Gregson.

Genet’s play The Maids is the most durable work to come out of the case, and it’s rightly performed frequently. The translation here by Martin Crimp elevates this version above many recent productions. Crimp mainlines chunks of Macbeth into the text, but this is logical given that the plot concerns the murder of a person in authority with the perpetrators under time pressure. Mercifully, the killing mechanism here is chamomile tea laced with barbiturates.

There are hints of Beckett when one of the girls says that they seem doomed to re-enact their role-play endlessly. Director Annie Kershaw steers the maids through their cycles of love and hatred for both each other and their mistress across a taut 90 minutes with no interval. I could almost have done with more.

Having looked at the original text, I believe the approach here is true to Genet’s intention of making us ponder how ritual and role-play can become blurred with real life. There are specific instances of this as the girls (as part of the dialogue) show they are struggling with the props for their game. And we learn that Claire holds the weapon of a truly dirty secret about Solange.

Carla Harrison-Hodge as Madame.

Photo credit: Steve Gregson.

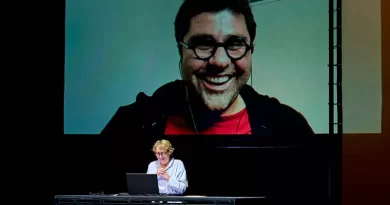

We begin with the elder maid Claire (played by Charlie Oscar) pretending to be the employer and abusing fellow maid Solange (played by Anna Popplewell) so viciously that it’s uncomfortable to watch.

I enjoyed aspects such as hints that Claire is employing a method acting approach that makes it difficult to leave her role. The production is calibrated as the girls create their mini-theatre. They also work themselves into a sexual frenzy. Genet is explicit about this – to a greater extent than suggested by Crimp – so the women are incestuous to boot. Sexual agitation, fallings-out, and reconciliations are all echoed by tension coming in from the thunderous weather outside. And Genet’s many good gags about an unseen half-naked milkman thrilling the girls all find their mark. Just occasionally we are in Joe Orton territory.

Oscar excels vocally both with what we realize after a while has been her excellent mimicry of Madame (a slightly androgynous Carla Harrison-Hodge) and the Estuary English accent she (Oscar) uses as her main servant character. If you didn’t know the maids’ true intentions, you might think that this is going to be nothing more than healthy catharsis. Kershaw injects switchbacks in the power balance worthy of Hitchcock and films like Rope with constant references to leaving tell-tale clues.

Set designer Cat Fuller shows flair and discipline in equal measure. Much of the performance area is padded white cubes suggestive perhaps of the asylum that awaits the girls. White is combined with shades of red ranging from the carnations referenced in the text to vermilion LEDs on a kitchen clock used to time the girls’ metatheatrical antics precisely while Madame is away.

As with the role-play, barely a second is wasted with exposition and the many good visual gags come in swiftly. Fuller is also responsible for the costumes, and I bought into Madame’s assertion that her red dress has been designed by Chanel.

Catja Hamilton’s lighting design is so subtle that those red diodes on the clock glow through the whole space. She illuminates Madame’s dressing-table mirror such that both characters and audience catch glimpses of themselves in it.

A central area sometimes becomes the street outside, even to the point of being lit by a gas lamp. Hamilton bases her lighting not just on stage directions but mere hints in the text. She has obviously pored over the dialogue. There are snatches of Vivaldi and pulsing single notes often suggest a hymn as the girls quote scripture.

Popplewell has the toughest challenge of the night, an extended monologue in which she must conjure up figures both real and imaginary from the Paris quartier outside. The speech should surely be an audition piece, and she envelops us in a whole world of the reeking and seedy down-and-outs with whom Genet spent most of his life.

I was impressed with Harrison-Hodge whose lines are far simpler; she relies on a brand of mesmerism to elevate herself in status and affluence. The maids have been playing at domination and submission, but Madame must truly dominate. Everybody is charismatic and sexually ambiguous. Madame is required to make Solange’s lust for her credible with the physicality of an earlier murder attempt involving heaving bosoms swelling out the bedsheet. More Orton.

Crimp removes all references to datable events. French colonies, monarchs, and known prison locations are omitted from the text. The central themes are primal and one of the many merits of this version is to make the plot timeless. Solange comes out of the role-play in a notable moment to confess that she is exhausted by it. I too left exhausted. This revival is spellbinding.

Annie Kershaw is a director who has come through Jermyn Street Theatre’s Carne Deputy Director Scheme. The Maids is a co-production between Jermyn Street Theatre and Reading Rep. It is at Jermyn Street until 22 January and then transfers to Reading from 28 January until 8 February.