“The Doctor”, Duke of York’s Theatre

Neil Dowden in the West End

12th October 2022

Created by Robert Icke, The Doctor (loosely based on Arthur Schnitzler’s 1912 play Professor Bernhardi) was a big hit for the Almeida Theatre in 2019 – now, after a Covid delay, it finally reaches the West End. Icke has made a reputation for adapting and updating classic works, and here he uses the basic storyline of the original play as a launch pad for an examination of contemporary concerns around medical ethics, identity politics, anti-Semitism, and trial by media. It may be a dramatized topical debate but it is staged with edge-of-seat urgency.

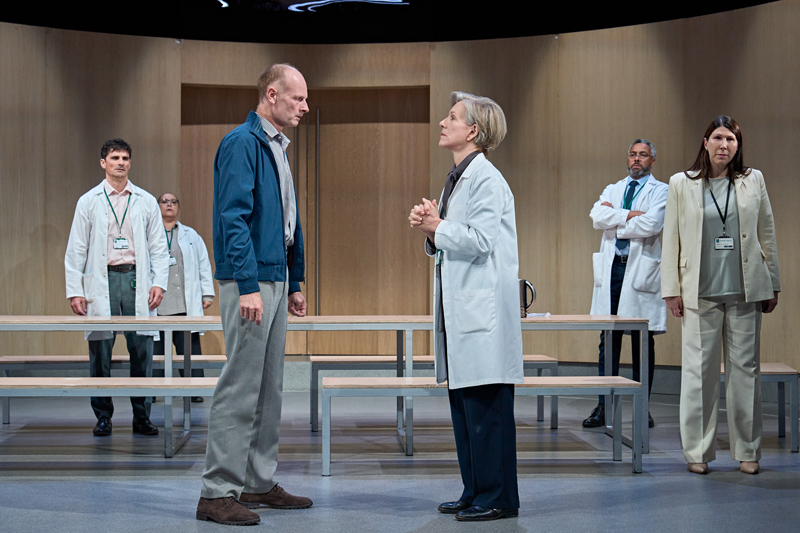

John Mackay and Juliet Stevenson (foreground).

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

The premise is quickly set up. In a medical institute, a secular Jewish doctor refuses to let a black Roman Catholic priest administer last rites to a 14-year-old patient dying of sepsis after a botched self-induced abortion. The girl’s parents are hurt and angry that their daughter did not get the spiritual send-off they believe in, as the case goes viral with an online petition against the doctor spiralling, a social media backlash, and a TV debate ramping up the pressure. With some of her colleagues highly critical and the institute dependent on financial backing from the government, Doctor Ruth Wolff is backed into a corner.

Wolff – the founding director of the institute which does ground-breaking research into Alzheimer’s disease – is a brilliant doctor, but her scientific detachment about being “crystal- clear” on all aspects of her work means she is intolerant towards others’ points of view. She did not want the priest to panic the girl who didn’t know she was about to die, but what were the “best interests of the patient” overall and who should have the right to make the decision? Wolff’s uncompromising arrogance may get her into trouble, but the anti-Semitic, misogynist campaign against her – which includes allegations that she herself is racist – turns into a witch-hunt that is painful to watch.

Icke has had the inspired idea of often casting male actors in female roles, white actors as black characters, and vice versa, which only becomes apparent as the play proceeds, thereby drawing attention to how identities are perceived and questioning the assumptions – or unconscious bias – we may have towards them.

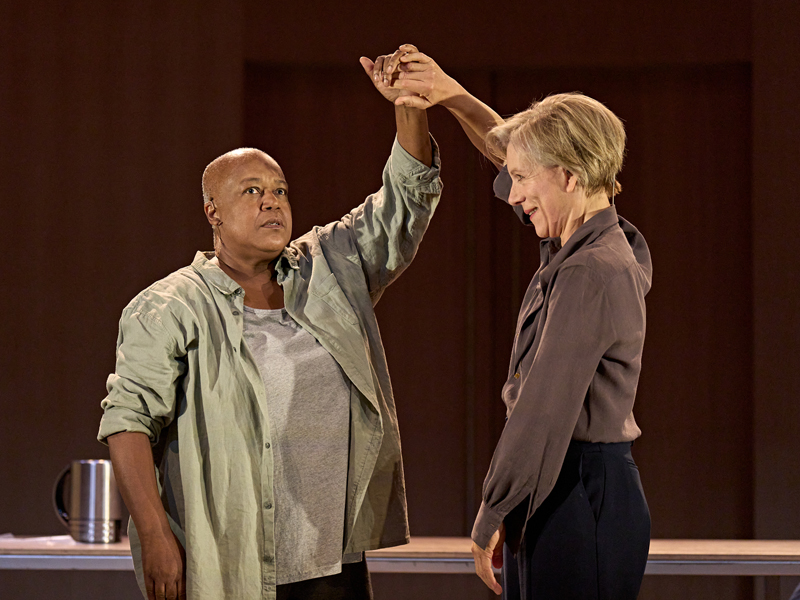

Juliet Garricks and Juliet Stevenson.

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Schnitzler himself was aware of his multiple identities as an Austrian Jew influenced by German culture in the last years of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and as a doctor turned writer, described by his Viennese contemporary Sigmund Freud as his literary doppelgänger. The play explores the intersections – and conflicts – between religion, race, gender, sexuality, and class, challenging conventional categorization.

Icke’s characteristically assured, slick production keeps things moving – literally sometimes with a slow revolve that slightly shifts perspective – so that the intense discussion doesn’t become too static. There is a gripping scene where Wolff is questioned – or interrogated – on television with the panel facing the audience while the doctor confronts them and we see her face in uncomfortable magnified close-up on a live feed.

Hildegard Bechtler’s stripped-down, clean-cut design with curving pinewood wall and doors, table and benches gives a clinical impression. And, perched above the stage at the back, percussionist Hannah Ledwidge’s edgy, rhythmic beats add tension to the action.

About half of the original Almeida cast return to this show, led by the magnificent Juliet Stevenson as the inspiring but divisive Wolff who is forced to re-evaluate her mono-identity as a doctor, as she can no longer separate her private life from her public role, with aloofness giving way to vulnerability.

Naomi Wirthner plays her chief work rival and opponent with aggressive opportunism, Preeya Kalidas gives her ex-colleague and health minister a slippery pragmatism, and John Mackay’s insistent priest later shows a more conciliatory side. On the domestic front, Matilda Tucker plays an abused transgender teenager who looks to Wolff as a substitute parent, while Juliet Garricks haunts the stage as the doctor’s dementia-affected partner who acts decisively before her own identity is lost.