“The Divine Mrs S” at Hampstead Theatre

Simon Jenner in north London

30 March 2024

April De Angelis is back tackling a subject at which she often excels: historical theatre. Her The Divine Mrs S opens at Hampstead Theatre, directed by Anna Mackmin. Set in 1797–1800, a crucial moment in the career of the 18th century’s greatest actress Sarah Siddons, it’s the third, most successful play De Angelis has produced in 15 months. It also forms an informal trilogy with two of her very finest: Playhouse Creatures (1993) and A Laughing Matter (2002), spanning Restoration actresses and the era of David Garrick and Peg Woffington.

Rachael Stirling as Sarah Siddons.

Photo credit: Johan Persson.

At 42, Siddons (Rachael Stirling) at her peak locks acting styles with her brother, actor-manager John Philip Kemble (Dominic Rowan, all roar onstage and wisecracking growls of envy off it) over his Theatre Royal Drury Lane’s casting and programming. Kemble can’t control Siddons’ performances, still less her propensity to faint at the end of a particularly egregious tragedy. Small wonder, Siddons’ real daughters have a propensity to die on her and dresses are too tight.

Kemble can’t help regurgitate the braggadocio learned from Garrick, but with less point. Rowan revels in the more-smoke-if-less-fire approach. By contrast Stirling’s Siddons ushers in modernity, as in her cool riposte to critic Mr Boaden (Gareth Snook in a recurring role) who notes: “You departed from tradition in the most extraordinary way.” “It’s quite simple … I just read the stage directions.”

Indeed this Siddons often refers to herself as a stage direction in the third person declaring an action up to the last moment, as with: “Siddons steps from the wings.” It informs Stirling’s performance: not entirely the adamantine Siddons shot with modernity, but slightly scaled down to contrast with Rowan’s leonine Kemble, who blowtorches his way around backstage too, if with more swearing and faster delivery.

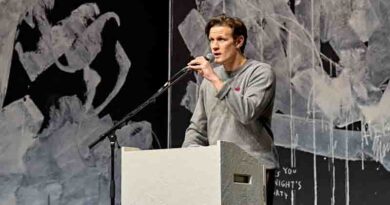

Rachael Stirling and Dominic Rowan.

Photo credit: Johan Persson.

That’s except when they’re both caught striking appalling sentimental stage attitudes in appalling plays. There’s a superb pay-off though in what they both realize is their finest performance of the Macbeths, introduced by a very real prop. And they’re comically united – over stage superstition.

By contrast Kemble understands Siddons so little he fears she might kill herself with a cheese knife and instructs her new dresser Patti (Anushka Chakravarti) to withhold it, sparking a tussle of loyalties: Siddons wins of course. Patti becomes her familiar, with the refrain, “Never say that out loud, Patti.”

De Angelis’ language comes freighted with quotations from Siddons’ memoirs and the time, leavened with later clichés like “under their own steam”, spliced with contemporary idioms like “Good luck with that”, and spiced with period quips. It’s often garishly funny: Siddons recalls being heavily pregnant dressed in salmon “like a prawn” as her disastrous Portia at 19. And plainer words best pierce the grief of news. A Siddons for our time.

Chakravarti enjoys nudging and swerving her straight-woman act around Stirling’s Siddons, springing some of Patti’s own surprises. Siddons can’t work out why Patti’s wearing all her clothes at once. A peek at what her brother tried on would have told her.

All three multi-roling actors dazzle in split-second changes. Snook’s oleaginous Boaden, even oilier painter Thomas Lawrence, Uriah Heep-like actor Percy Scraggs, and honest jobbing actor Charles. Bar Boaden, they’re a little undernourished.

Sadie Shimmin’s Mrs Larpent, the power behind her censor husband, writhes in her contradictions: it’s a delight. A besotted Lady Bountiful she’s also trembling Mary Whitehouse, delicately tortured by admiration, desperate for Siddons to justify the ways of woman to prudish goddess: for each new play’s licence to go on. As raffish comic Cowslip, Shimmin taunts Stirling’s Siddons with a threat to everything Siddons has established. She’s also a brief madhouse Turnkey in a singular scene that might have enjoyed a few more effects.

That madhouse is the nadir of one of the superb Eva Feiler’s roles, as Larpent’s maritally abused daughter Clara. Clara flees to Siddons who gives conventional – i.e. bad – marital advice which ends disastrously. Or does it? It’s a transformation of De Angelis farce born of near-tragedy and you want to cheer at the apotheosis. The crux of the play though lies in Feiler’s quicksilver depiction of poet/playwright Joanna Baillie. The play hinges on this antithesis of Larpent and Baillie: the men simply interfere, in one sense get in the way of what it is to construct a public femininity (Siddons) and deliciously as Feiler’s Baillie puts it “deconstruct the patriarchy” – which gets a rafter-cheer.

Lez Brotherston’s magnificent backstage set emulates Drury Lane, with its galleries and ascents of gas lamps; Mark Henderson’s lighting crops the view and expands just as atmospherically. It’s a detailed bare-boarded backstage, though oddly the lower downstage and sides are hardly inhabited, losing their point. Upstage, beyond the curtains we’re offered a gulph of footlights and darkness, with Max Pappenheim’s sounds of audience beyond, and a neat witty score.

De Angelis’ finest play for some years, The Divine Mrs S bursts with potential and is fretted with intrigue. Women’s roles are strongest; though it might have seemed perverse to leave out Kemble et al. The whole Drury Lane scene proves impossible for De Angelis to resist, given her brilliance in depicting period theatre. In any case, there’s a pay-off with a sharp prop. Likely to settle into an enormously satisfying work, notwithstanding small caveats, The Divine Mrs S earns – and will earn – the standing ovation it received on press night.