“The Boy with Two Hearts”, National Theatre, Dorfman

Simon Jenner on the South Bank

14 October 2022

Cramped in car boots, in hidden lorry compartments, not breathing. How much has changed in 22 years! This, though, is a true story you’ll know, if you heard it on Radio 4’s Book of the Week.

Shamail Ali, Ahmad Sakhi and Farshid Rokey.

Photo credit: Jorge Lizalde-Studio Cano.

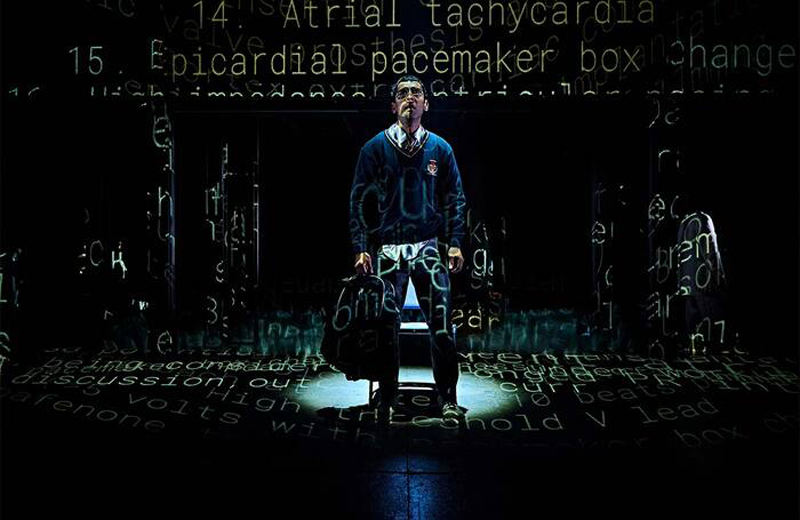

Two brothers (Hamed and Hessam Amiri) have written their family’s recent history. The Boy with Two Hearts, adapted by Phil Porter and directed by Amit Sharma, was first staged at Wales Millennium Centre in October 2021. Transferring to the National’s Dorfman a year on, Hayley Grindle’s set fuses neatly with Hayley Egan’s video design to produce a compact storytelling that is both high-impact and accessible. Schoolchildren are present and spellbound.

This is the second NT Dorfman play in a row to highlight the plight of minorities – Francesca Martinez’s magnifient All of Us, also partly autobiographical, focused on disabilism, has only just come off.

“You want your children growing up in a country run by thugs?” Fariba (Houda Echouafni) is the pride of her husband Mohammed (Dana Haqjoo) who – if anxiously – wholeheartedly supports her platforming in the market-place for Afghan women’s educational, career, and lifestyle rights: suffering under the Taliban, now ruling Afghanistan for four years. It’s 2000; Fariba’s stand means the Taliban will kill her. The family escape that night, selling all they own to friendly neighbours. Soon they’re in Moscow.

Grindle’s small circular stage, with girders and gantry, exudes a minimalist brutalism. Versatile – with a central horizontal panel between upper and lower which reveals compartments the whole family cramp in – it also hosts Egan’s video design, with conversations colour-coded to a vivid piece of clothing each of the five actors wear. The narrative’s brightened by the way it projects words as things they connote: thus rain drops in multiples of “rain”, captions creatively embedded. A font-fest of typography signals modes of transportation the family take: their variously shaded names squeeze inside a car boot; “road” repeats itself like cat’s-eyes; the white word “aeroplane” heavily takes off along a runway.

Ahmad Sakhi as Hussein.

Photo credit: Jorge Lizalde-Studio Cano.

It’s not just Fariba who’s in peril, and this lends urgency to the first half, and the second half’s outfall. Eldest son Hussein (Ahmad Sakhi) has a life-threatening heart condition and needs treatment in the UK or USA. Initial banter between him and the two brothers, Hamed (Farshid Rokey) and Hessam (Shamail Ali), gives way to edgier bro-talk, Man United vs Arsenal taking on the force of litany as Hussein undergoes heart attacks. Lighting by Amy Mae takes on a spectral flashing at this point, with Tic Ashfield’s sound turning up the heartbeat. Movement direction by Jess Williams spasms this moment, integrating it into the general sway and snap of the whole production, which plays across continents at times like an intimate ballet.

The superb Afghan singer Elaha Soroor, who co-composed the vocal music with Ashfield and supplied the lyrics (“I am from the tribe of rain”), appears on stage, commenting on stages in the journey; standing a bit like a spirit guide when Hussein suffers cardiac trouble.

The first half’s all flight. Each of the party peel off unnervingly in a whip of fabric to become someone else, warm, hostile, gangsterish or plaintive. The alternating kindness and cruelty of strangers hardens them all, particularly the boys. Farsi with visuals in translated English is both minimal and effective.

Dynamics alter, the brothers grow differently. After the family’s robbed in Moscow, Hamed mistrusts all-comers, behaving in a quasi-thuggish manner, Rokey’s expression crossing bulldog with boxer; especially when finally at school. At the Ukraine border they meet other refugees, including Zara with a harrowing tale (curiously Zara’s an enlarged silhouette). Again, nothing changes. There’s respite too, in an Austrian camp which because of Hussein they feel they must quit. The first half ends with an edgy sequence of contacts hustlings, lorry cramps, being intercepted, thrust into the dreaded Calais camp.

Though the pace has to alter, the second half’s fraught with health anxieties, the warmth of medical staff, university and a finale where the audience are thanked (what on earth have we done?) and affecting images projected. It’s not a subtle telling: how could it be? It’s vivid, though: video and set clarify speakers and situation with typography traceable as a CT scan.

Intense lucidity, a refusal to make this true narrative anything other than it is, is a tribute to Porter’s sensitivity, wholly devoid of more than deft stagecraft, refusing other than a straight-through narrative. There’s a simplicity of feeling that might border on sentiment, but it’s clearly aimed at a younger audience too. Actors are all superb, though Ali, Rokey, and Sakhi relish the chance to jump out of their familial skins to brandish scalpels, pistols, AK47s, and torches. Despite the ending’s warmth, you come away not with looking at this family’s plight, but your own. How to condone the toxicity? Those school children will answer us.