Renaissance: A European Theatre Convention Project

Dana Rufolo on anticipation of normalcy

Renaissance, the most recent project of the European Theatre Convention, gave participating theatres a chance to imagine the post-pandemic world where theatres are running again. Enthusiastically, 22 theatres from 18 European countries accepted the invitation to independently produce a five-minute video in which they artistically expressed their anticipation of practicing theatre again in a post-lockdown return to normalcy.

Renaissance is “about reopening theatres” and offers one of the creative solutions to recovery that is being matched by the economic solution of increasing the EU budget so that € 2.46bn are to be dedicated during the next seven years to the cultural and creative sector in order to help the arts recover quickly from the pandemic.

I hope that in reading this report on Renaissance, readers of Plays International & Europe are inspired to follow suit in one manner or another by staging or filming their own imagined scenarios regarding the rebirth of theatre. Renaissance started as the brainchild of Serge Rangoni, the artistic director of Théâtre de Liège in Belgium, one of the 44 member theatres from 25 countries of the European Theatre Convention. The project went ahead as an “artistic international collaboration” using digital theatre as an “open and democratic space”. The videos have been released for public viewing and are available at:

https://www.europeantheatre.eu/page/activities/renaissance

Each of them has English subtitles.

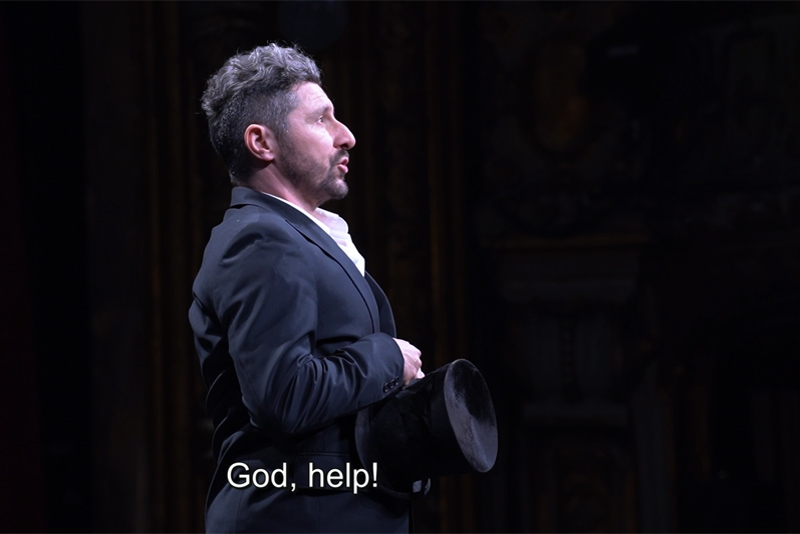

European Theatre Convention, Renaissance project, Croatian National Theatre.

Briefly summarizing the themes and images in these 22 videos, one thing is clear: they all express the relief and anticipation of theatrical activity for a population that has been affected to its core by interdictions against gatherings in public spaces. Most frequently, the writers and filmmakers chose to film a mock preparation of a production in high speed – right up to the opening night when the stage crew and actors face a soon-to-be-filled auditorium. The Croatian National Theatre in Zagreb made such a representative film. Written by Mirna Rustemović and directed by Damir Markovina, the film focused on the stage itself. The question was, “How are we going to restart?”There was a mixture of movements, voices, and images reveling in apparent confusion (men in suits and top hats bustling around on stage as if waiting for the show to begin), references to death (we are told that someone’s father died and will be buried in three days), women’s outrage (“women taught you to read live …”) and a plethora of awesome backstage warm-ups of actors, opera singers, ballet dancers who “face a distant and eager audience.” The film was like a practice warm-up for the genuine re-opening.

The undying spirit of performance was captured by Trnava, Slovakia’s theatre Divadlo Jana Palarika in Trnave in what was perhaps the most allegorical of all 22 films. A storyteller reads to a child who wants to be king and is given a prop crown; he grows up and becomes an actor. When old, he hands over his prop crown to a new child. And so the human desire to dramatize is forever reborn.

European Theatre Convention Renaissance project, Göteborgs Stadsteater.

Less optimistic, the”digital theatre” contribution from Ukraine’s Dakh Theatre – Centre of Contemporary Arts in Kiev, a piece written and directed by Vlad Troitskyi, used prismatic images, some of earthenware human heads, asked why the world is unfair and cruel. The film continues by questioning: Why are we here? If not for God, then for people — but whose people? A partial answer comes from the sung William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 77 (“Thy glass will show thee how thy beauties wear”) and music by the band DakhaBrakha that defines its “Ukrainian polyphonic” style as “ethno-chaos”.

European Theatre Convention Renaissance project, Göteborgs Stadsteater.

Undoubtedly one of the most ironic Renaissance films was from Sweden’s Göteborgs Stadsteater – Backa Teater. In front of the theatre building, presumably still shut due to lockdown, an actor dressed in a harlequin costume and wearing a gas mask jumps up and down shouting, “Make theatre great again!” repeatedly. Not only was the actor adapting to his own purposes a phrase associated with a former American president whose appreciation of the arts was non-existent, lending a shadow of desperation to the statement itself, but the actor with amazing stamina was filmed perpetually jumping and shouting his slogan as day turned to blackest night in real-life conditions, which meant that passers-by from time to time were filmed walking through the space where he was jumping — and, frankly, not a one of them showed much interest in his routine, nor in what he was saying.

German-speaking theatres were highly adept at exploiting the potential of digital media. Germany’s Staatsschauspiel Dresden suggested that the pandemic offers a chance to renew creativity in their sophisticated Renaissance film that used the display format of a mobile phone, and in Vienna, Austria’s Volkstheater video Leeres Theateritalics (Empty Theatre) with words by Heiner Muller, the actors who feel “lost in the world” in a gapingly empty theatre building gradually transmute into digital images of themselves. The theatre building follows suit.