Pro-English Theatre, Kyiv, from a bomb shelter

Alex Borovenskiy talks to Jeremy Malies from a city under siege.

8 April 2022

Alex Borovenskiy.

Photo credit: Stanislava Ovchinnikova.

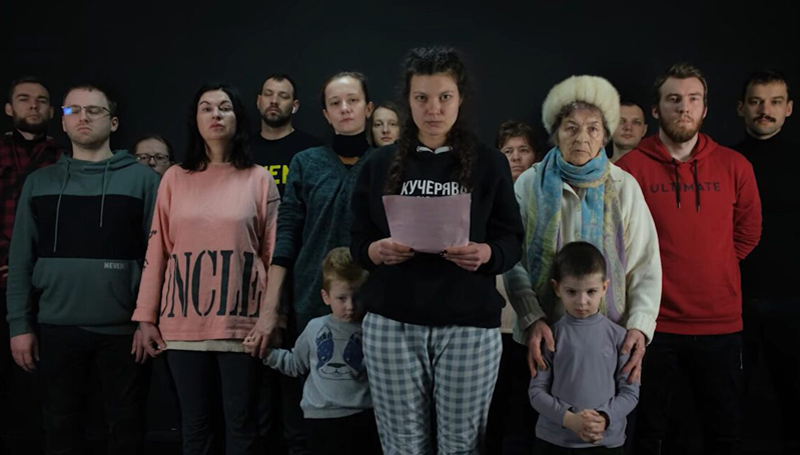

In the ordinary run of events, the Kyiv-based company ProEnglish Theatre would be performing Hedda Gabler and preparing for their own adaptation of works by the American science-fiction writer Ray Bradbury. What is in fact happening is science fiction of a sort; actors from the company together with family members and locals are using their basement theatre space as a shelter while the Russians bombard the city. It’s futuristic in that company director Alex Borovenskiy sees this as indisputably ‘the final war’ but one in which Kyiv will not fall and the personification of evil in the form of Vladimir Putin will not ‘reach for the red button’. As the Ian Dury song has it, there are reasons to be cheerful if only because the dustbin men are carrying on regardless and the city’s garbage is still being collected once a week.

The metatheatrical is an ever-present in the life of Alex and his actors now, and he describes the increasing encroachment of troops and bombardment of the city as “a pretty big show”. Actors and relatives have taken to sleeping in the performance area within the shelter and two children are even using a bed that only days earlier had been a stage prop. Pirandellian levels peel away as events become increasingly violent and unfathomable. Nobody is quite sure if the bizarre surroundings are reality or part of a script. Are they citizens of Kyiv or characters in a violent play?

My opener is hesitant even apologetic. Am I trivializing the events on the streets above (a shopping centre is being bombed as I type this) by wanting to talk about theatre? Or might it be refreshing for Alex, possibly reminding him of what he should be hoping for as an outcome?

Hedda Gabler. Alina Zievakova and Stan Galiant.

Photo credit: Andrii Kubrack.

He is keen to balance theatre and politics and sees them as inextricably linked: “I’ve been doing quite a few interviews and yesterday while I was talking to a journalist, I heard a monstrous explosion outside. I’ve been trying to analyse my reaction. As a theatre director I always explore how people react. And the sound of artillery doesn’t faze me now – it’s part of daily life. And that scares me in retrospect. I don’t want to get used to the sounds of explosions and be okay about it.

“Yesterday I had a rehearsal. Because we have started performances during a war, the piece Hitler Takes Poland seemed appropriate. The rehearsal didn’t go particularly well. It’s a one-hander and the performer, Anabel Ramirez, just for once wasn’t quite at the top of her game. And then the sirens went. Anabel was in character to such an extent that she didn’t hear them. But I heard them alright. Suddenly, the performance started to make sense. It just clicked – everything came together. I thought: ‘Well, that’s the sound we’re going to use!’ The irony is that those were the real sirens – not the ones that I had chosen.”

We’re talking on WhatsApp and I say how surprised I am that the country’s infrastructure is holding up with everybody seeming to have an Internet connection. “There are heroes right across the country who are keeping services going. The war isn’t that old and we’ve already had the dustbin men come three times! Ironically, we had erected a protective barrier around the theatre and had to dismantle part of it so that the dust cart could get in. The driver said: “Wow! Kyiv you are magnificent!” And of course it helps to have the right mayor, Klitschko, who has been twice a world heavyweight boxing champion. He is the best!”

Alex Borovenskiy, theatre director, Raise Hryhoriivna, a neighbour.

Photo credit: Daniil Prymachov.

I ask if having one of the greatest boxers ever to don a pair of gloves in charge of city hall adds a little steel to everybody. “As Ukrainians and city residents we were a little sceptical at first. We have a former boxer as mayor and a former comedian as president. But then when all this went off, they both stepped up to the plate magnificently. Their responses have been exemplary. But it’s not only them – there has been a change of perspective. Everybody is united now. I support our government totally and the nation stands as one.”

Does Alex see any irony in the background of current leaders? Boris Johnson has written a biography of Churchill and sees himself as a world statesman of consequence but he behaves like a comedian. Volodymyr Zelenskyy is a former comedian and he is impressing everybody with gravitas and physical courage.

“Leaders are measured by what they do not what they say. The real criterion is always your actions – it’s what finally puts you into world history. I don’t know what Putin thought but what he did has put him out of history. The reactions of some of the European countries have been ridiculous. They are saying they are going to support Ukraine but refuse to do anything of a military nature.”

Lilian LeVos in Into the Blue.

Photo credit: Andrii Kubrak.

Alex suggests that we do indeed stick to art because he tends to become increasingly angry during political discussions. But ProEnglish Theatre has fused the two with its output, notably a reworking of “The House of the Rising Sun” and a new lyric: “Now the only thing simple men need / Is protection from the sky.” His disappointment that there has not been a no-fly zone is palpable. He says: “Sure, there is ammunition coming to support us but it isn’t tactical. Some of this is minor munitions – the anti-tank stuff. But anti-air stuff which would really help could be faster and stronger. Bear in mind that this is Europe. Putting up our country as a buffer – it’s humiliating. Europe did something similar in 1939 and look what it brought us. We are repeating the same thing. It took the whole of Europe 60 to 80 years to gain a full perspective. Aren’t we educated? Don’t we read history books? It’s a simple lesson in historical literacy.”

Putting up our country as a buffer is humiliating.” Alex Borovenskiy

The reworking of the Animals’ smash hit (the song is far deeper rooted and dates to the 1930s) has another line about “getting one foot on the train”. I congratulate Alex on his bravery in not seeking to board a train himself and he tells me that the line is about people boarding trains to come back to Ukraine, a number currently estimated at 320,000 by CNN. “Many people have fled – three million by now. Ukrainians have left the country but then there has also been a tremendous influx. Many Ukrainian men ex-pats are coming back. Not all of them which is understandable and it’s okay – but many. Not everybody has to fight. I’m not fighting myself but I’m not going anywhere either. I’m here in the theatre. Ukrainian men are coming back to help wherever they can. It’s volunteer help, humanitarian help. Some of them do sign for the military. It’s tremendous how Ukrainians are standing together. This country, this nation, cannot be defeated. My sister came back from the Czech Republic. Now she’s in Uzhgorod helping, co-ordinating, volunteering. She wanted to come to Kyiv. I’m glad she didn’t.”

Video footage of the theatre’s basement living quarters shows hundreds of brown-paper-wrapped books crammed into windows as bricks to protect against explosions. There are also books in a small library that are being read. It’s quite a distinction. The titles are legible in the video, and I note The Empty Space by Peter Brook whose title seems more than usually meaningful.

The City Was There rehearsals. Alex Borovenskiy (foreground left) coaches actors

Taras Kravchuk, Andrew Anisimov, Vladimir Zubkov.

Alex continues: “Luckily, we are a small independent theatre so we were always located in a basement and it used to be an official bomb shelter during WWII. It is indeed our ‘empty space’. We came here on day one of the war. This theatre is the centre of my life and it happens to be in a protective basement. Perfect combination! And right now in our performance room – which we call the ‘Hollywood Room’ – we have ten people sleeping where we used to perform to audiences of 40 or so. There are still curtains, stage lights, and even a sound desk. The occupants are a kind of audience because they experience the war every day. I never thought I’d experience a show like this in my life.”

Leaders are measured by what they do not what they say. The real criterion is always your actions.” Alex Borovenskiy

I ask Alex if he fears experiencing an even bigger show should Kyiv fall. “Firstly, Kyiv is not going to fall. If it does, Moscow should fall together with it. Technologically, logistically, digitally – they don’t have enough power. If they enter Kyiv, they will find every rock is against them. Every person, every babushka. You may enter the city but you’re not going to make it out alive. Kyiv can be potentially destroyed tactically. But again, watching Kyiv, a major European capital, being flattened from the air, now that would be humiliating for the whole world.”

Returning to art but somehow knowing that politics will reappear I ask about a poster advertising an “Acting Shakespeare” course. What experience does ProEnglish Theatre have of Shakespeare and what might the company want to do with his work? Surely the many plays about usurpers and evil invaders being repulsed will appeal to him?

“Last year I finally felt ready to mount some Shakespeare and we did. We staged a project called Forgetting Othello. It’s perhaps 80 per cent based on the original text while 20 per cent is modern monologues themed around the Middle East. For me, it’s all the story of Europe. The island where Othello and the Turkish fleet hit the storm suggests the whole of Europe in how I saw the play. The Turkish ships can be likened to the orange dinghies of refugees, many of them containing Syrians who are trying to cross the Mediterranean for a better life.”

The City Was There. Eugene Bondarskiy, Tanya Sydorenko, Kira Meshcherska.

“Our Shakespeare will have a simple strict message”

“So I changed the whole story – it’s so ironic. No – not ironic. It’s so strange because it’s all about receiving or not receiving refugees, chaos, destruction in one’s native land. We inserted a powerful quote from Benedict Cumberbatch. At a Save the Children event, he said: “No one puts their child in a boat unless the water is safer than the land.” The original material gleaned from refugees and written about them is valuable. I never thought we would have refugees in Ukraine but they say art predicts life.

Once this whole show is over and Ukraine wins, we will think about what sort of Shakespeare we’re going to do. I’d like to have something like Coriolanus – something strong and with a simple strict message. Ukraine has become a nation of fighters. We would need Shakespeare that speaks very directly without any innuendo. It would say exactly what we mean, what we want, and what we propose to do. That’s Ukraine now, that’s what it will be.

Alex is not a native of Kyiv but moved to the city after university. I ask about his upbringing and education. “I’m 42 and originally from Cherkasy which is a quiet town in the centre of Ukraine on the Dnieper River around 250 kilometres to the south of Kyiv. I moved to Kyiv immediately after university and my first degree was as a teacher of English plus world literature. When theatre hit me, I was already 28 and I started taking theatre courses at drama school. That was my on-the-spot form of study. When I started to get enough knowledge and experience, I set up a small studio just as Stanislavski did. It took us four years to really say we had formed a theatre and this coincided with the first English-speaking professional actor working with us in 2018.

“I didn’t have a single defining moment that propelled me into theatre. I had always been a theatre lover. When I came to Kyiv, I responded to the city’s active theatrical life. You look at the listings of what’s happening in Kyiv, in normal conditions of course, and there will always be at least six big interesting productions.

“There were a few things in English going on as experiments in the state theatres before I set up ProEnglish Theatre. A major production was The Crucible at the Molodyy Theatre. I was invited to participate in a community theatre piece and I played the villain. We had an enthusiastic audience – mostly relatives and friends. But after the performance I reflected: ‘No! This isn’t how it should really be done. You should know how to act.’ So I went to study. I had had the experience of stepping out into the limelight but knew that it was not enough. So, as a beginner, I studied acting for three years in different drama schools and did a lot of personal research. English had always been my thing and I read a lot – believe me – a lot.

Stan Galiant and Julia Sosnovska in Pinter’s The Birthday Party.

“I read about Lee Strasberg, I read Stella Adler books, I read Sanford Meisner. It was self-education that somehow all came together but didn’t coalesce at an instant. It was a gradual realization that theatre is the biggest thing – the biggest show I guess. Theatre and our community outreach never stop. We’re working at so many humanitarian levels. My colleagues and I are out at pharmacies helping babushkas to buy medicine and of course we host people here. But I also make sure that I have rehearsals every day and I will have a rehearsal straight after talking to you. It’s the only thing that makes sense in this world right now.”

Alex expands on the Hitler Invades Poland show. “It’s based on a book by the Australian writer Markus Zusak. He wrote this best seller called The Book Thief. (There is a 2013 film starring Geoffrey Rush and Emily Watson.) It’s about the small town of Molching in Nazi Germany. We see the whole thing from 1939. The book depicts local people who didn’t want to go to war, who didn’t want to support a fascist regime, but are obliged to. It has a clear message to me because it’s a history in reverse. Because what Russia is doing now is pretty much … no … it’s exactly what fascist Germany did. [I spoke to Alex well before there were reports of forced deportations of citizens from Mariupol to Russia which have suggested even more WWII parallels.] What’s happening to this small town of Molching in the play is what is happening to nearly every town in Ukraine right now. So, I took this text and today we came to the moment in 1942 – the first bombings of Germany just as Kyiv itself began to be bombed. It’s a strange feeling.”

Alex Borovenskiy. Photo credit: Daniil Prymachov.

“I read Peter Brook’s The Empty Space 15 times”

I ask Alex to take himself back to his period of intense study both as practical work and theory. Did anybody else influence him? How about the Jacques Lecoq method? Grotowski?

“Peter Brook was the most important author I read. And I read Stanislavski in English – that was strange. Later, I went back to the Russian. I printed Peter Brook’s The Empty Space out in a large font size. It explains to me not just the technology and philosophy of acting but also its essence. I read it 15 times.

“Grotowski of course. I’ve been to the Grotowski Institute in Poland and taken a course with his successors. The physicality of acting is important to me. I’ve created several performances based on the existence of the actor in space. And because we are the ‘poor’ theatre in terms of being independent – we don’t have much financing – that is how we must build our performances so Grotowski is a big influence on me.

“Lee Strasberg is another influence. Some of my friends, Valera Simonchuk notably, have studied at the Strasberg Institute and they returned and shared their knowledge with us. Normally, Ukrainian theatre doesn’t have much access to these resources because by no means everything is translated. Ukrainian theatre is heavily rooted in the Stanislavski system and it doesn’t take so much from English, French, and Polish drama. ProEnglish Theatre tries to absorb the best.”

I give a faltering phonetically transcribed version of what I know to be a message of defiance that I have heard on video from Alex without knowing what it means. “Thank you for saying it and for asking. I’m trying to put this phrase into every interview. You just said: ‘Putin – go fuck yourself!’ The penny drops and I realize that this dates from the incident on Snake Island when a Ukrainian coastguard patrol told a Russian warship what it could do. “These cuss words show the position of Ukraine. They show that this is no time for diplomacy or being polite. It’s time to stand strong. I don’t know if the vulgarity is a good thing; that is something to be explored later in art and literature.

“There is prohibition now in Ukraine but during the early days we still had some alcohol and in very emotional toasts of an evening we would drink to the people who had died recently. I have friends who have been killed. The toast is ‘Let Putin die!’ I never thought I would wish somebody dead but we really want him dead. I believe the whole world does – perhaps not so openly – but we are voicing it here.”

Photo credit: Canstock.

Martin McDonagh is iconic in every sense

My predictable question as to Alex’s favourite dramatist produces something which is by no means a shock but perhaps slightly out of left field. “Martin McDonagh is a phenomenal writer. It’s my dream to direct every one of his plays.” We fall to discussing McDonagh and The Beauty Queen of Leenane as produced last summer at the Chichester Festival Theatre. He enthuses about a version at the Golden Gate Theatre (a state-funded venue) in Kyiv only this January directed by Maxim Golenko that Alex found suitably bleak, raw, and cold.

“As a drama school project I did The Cripple of Inishmaan. It wasn’t the best in terms of technical matters but I still loved the message and the writing.” McDonagh is obviously popular in Kyiv and Wild Theatre have staged The Lieutenant of Inishmore which they transferred geographically and culturally to rural Ukraine and retitled Kitten after the signature cat. (“Not recommended for children and people with fragile psyche” is a caution I find in online publicity material for this black comedy.) The production team had fun with the Orthodox tradition of placing a religious icon in a corner of a room and had a picture of McDonagh treated in the manner of an icon at the edge of the set.

So what is his broad view of current events and their long-term consequences? “It’s a cultural moment but primarily a huge moment in civilization. It is surely the last war. This is an experience to be documented and reflected in every conceivable form of communication.”

I ask if it disgusts Alex that Putin uses phrases such as “a tactical incursion into Ukraine” rather than the word “war”. Does this make his blood rise? “Not anymore. I don’t know if anybody in the world is still listening to what Putin says. Now, it’s only the threat of the nuclear warheads and perhaps the gas supply. These are the two things of consequence in what he says. It’s all such blatant lies that it makes us laugh. His latest is the allegation that, with funding from the US, Ukrainians were experimenting with coronavirus in their laboratories and this is retribution! But it’s troublesome that this kind of propaganda may still work on the Russian populace. He has been pretty much excluded from Europe now but no form of expulsion will stop the Russians because they simply don’t give a hoot. The world should stop listening to what he says. He’s an illogical idiot with serious mental problems.”

The art shelter residents include children and several cats.

Photo credit: Daniil Prymachov.